PITTSBURGH (RNS) — Hill Brown will never forget the first time they administered naloxone.

The person was lying on the ground, eyes closed, ragged breathing, one ear turning blue. He had already been given one dose of naloxone, so Brown administered a second dose and gave him a rescue breath.

“He started sort of sputtering, and within about 30 seconds his ear totally changed color and he sat up. That is the speed of naloxone,” Brown told Religion News Service. “Without naloxone, this person wouldn’t be in the world.”

When administered, the naloxone nasal spray can reverse an opioid overdose so rapidly that its effects have been compared to a resurrection. And amid the relentless rise of overdose deaths, the Food and Drug Administration’s March 29 approval of over-the-counter Narcan is ushering in new access to the miracle drug long championed by harm reduction advocates.

A resurrection drug in time for resurrection Sunday.

“Spiritually, theologically, I see it as giving people a second chance, like a second birth. Or maybe their third chance or 99th chance or 10,000th chance,” said Kevin Nye, advocate and author of ”Grace Can Lead Us Home: A Christian Call to End Homelessness.”

“If Narcan is able to make a difference, which it very often is, that person comes back almost like you see in the movies,” said Nye, who has held dozens of naloxone trainings.

During the height of the pandemic, he hosted virtual trainings specifically geared toward Christians. He joins many advocates and people of faith who are welcoming the news of over-the-counter Narcan as a positive next step.

Still, religious folks aren’t always receptive to harm reduction methods — which focus on minimizing negative consequences rather than punishing offenders — when it comes to the opioid epidemic. Part of this resistance, according to Nye, comes from the myth that people who use substances deserve to suffer because doing so is sinful and selfish, rather than a result of addiction, trauma or a host of other individual and systemic factors.

“For me, that’s just a devastating misunderstanding of grace,” said Nye. “Grace says, who cares what we deserve? God threw that out the window for us. … We are loved into healing, not loved because we are healed.”

Brown views the approach of harm reduction as a way for Christians to join God in siding with those who are most marginalized.

“We are centering people who use drugs, uplifting those folks and making sure they have appropriate services to take care of themselves and to get the support that they need. That is, I think, God-filled work,” said Brown, the southern director for a multifaith group called Faith in Harm Reduction that fosters connections and resource-sharing between faith communities and people who use drugs.

According to Brown, a lot of churches end up doing harm reduction work they didn’t think they were going to do, especially in the South, where harm reduction programs often face legal barriers. As part of its work, Faith in Harm Reduction often teaches faith groups how to provide, store and administer naloxone.

The group also provides theological resources for preaching about harm reduction from the pulpit, including a blessing of the naloxone written by the Rev. Erica Poellot that asks the Creator to “bless the people who need this medication to live / that the breath of life and the reach of love restore them to wellness.”

RELATED: New book invites Christians to rethink homelessness

With the increased access to naloxone and the Biden administration’s removal of barriers to prescribing buprenorphine, a drug used to treat opioid use disorder, there have been a handful of recent victories for those suffering from opioid addiction.

“The more options there are for people to get naloxone the better,” said Dr. Jim Withers, founder and medical director of Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net, medical director of Homeless Services at Pittsburgh Mercy and founder of the Street Medicine Institute.

“I think it’s just another avenue for people to get access to it and share it,” Withers said about the FDA’s decision. “Obviously, we give out a lot of naloxone already, as do other organizations.”

When Withers first traded his lab coat for street clothes to meet the medical needs of folks he calls “rough sleepers,” he was the only person in the city providing medical care to that population. Three decades later, street medicine has become its own established field.

“The only way to really connect with people is to go to them. In the case of people living on the street, you get a backpack, you go out, you try to gain trust, and listen.”

Withers calls himself the “kind of Christian that works for social justice,” and he finds that harm reduction is a key component of the care his teams provide.

Nurse practitioner Danielle Schnauber, from left, outreach specialist Maisie Taibbi and Dr. Jim Withers of Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net on routine outreach rounds in Pittsburgh. Photo © 2023 Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net. Used with permission.

The street outreach organization Bridge Outreach is another Pittsburgh group that regularly distributes Narcan. The seeds for the organization were planted in 2015 when founder Dave Lettrich, who was then in seminary, became friends with several people who lived outside. Since then, Lettrich has “deconstructed and reconstructed” his faith several times over.

“I never saw it as a mission, from the faith-based Christian sense. But I believe that within all religion, regardless of our faith, at the root, there is a call to engage in humanity and to see others in a way that does not judge,” Lettrich said about Bridge Outreach.

The group adopts a relationship-driven model that prioritizes building community with people living on the streets. Then, if that person requests services such as housing, medical care or naloxone, Bridge Outreach helps provide access.

Lettrich told RNS the group typically has 300 to 400 clients at any given time. While it partners with other groups to meet client needs, Bridge Outreach directly provides harm reduction services, distributing just under 3,000 two-dose naloxone kits a year.

“We’re training and we’re distributing to individuals who either use substances or are around people who use substances. And we’re following up, having conversations. And that’s where our reporting comes from. Every time we see somebody, how’s your Narcan? Do you need any more Narcan, yes or no? Have you seen overdoses recently?”

Through this reporting, Lettrich says the group has tracked over a thousand overdose reversals thanks to naloxone.

Though the FDA’s decision likely won’t directly impact Bridge Outreach’s naloxone distributions, Lettrich celebrated the move. He said it could especially help offer access to those who fear the stigma associated with opioid use — it’s a lot less intimidating to get Narcan via a pharmacy shelf rather than having to go through a doctor.

RELATED: In ‘Raising Lazarus,’ Beth Macy summons the stone rollers

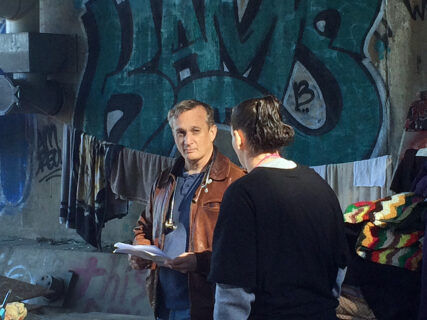

Dr. Jim Withers listens to a woman who is experiencing homelessness in Pittsburgh. Photo © 2023 Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net. Used with permission.

Yet even with increased access to naloxone’s resurrection promise, many Christians ministering in the thick of the nation’s opioid crises are still feeling closer to Good Friday than Easter Sunday.

“Holy Week doesn’t have the same significance to me that it did, in that it tends to be a focus on resurrection, newness. I more identify the suffering. The resurrection, for those who suffer, sometimes never happens,” said Lettrich. “If I was going to relate anything to Holy Week right now, it would be that shared experience of suffering and trauma that Christ had at this time, as well as the individuals we’re connected with.”

Advocates remain concerned about the future price of over-the-counter Narcan, which will hit shelves later this summer. In Manhattan, a two-dose box of Narcan currently costs about $98 without insurance, The New York Times reported. And advocates add that the war on drugs is very much alive and well, with state legislatures looking to pass harsher drug penalties for crimes related to fentanyl.

“There’s a way to just save the folks that we cherish and know that God made and adores, and that is by stopping the war on drugs today,” said Brown.

Though Brown welcomes the life-giving impact of Narcan, they hesitate to compare it to Christ’s resurrection, which Brown said was about ushering in a new reality and beginning liberation work in earnest after being persecuted by the state.

“I’m afraid that we’re not to a resurrection era for people who use drugs. We are still muddling through, dealing with the Roman guard of the moment. We haven’t seen people who use drugs for who they are,” said Brown.

“It’s a kind of healing in the world, but it’s not the resurrection I’m looking for.”