Business Insider ran a story Sunday about the rise of Mormon-themed anonymous online confessions. Such confessions aren’t exactly new—see this blog which attempts to gather all of the Mormon-themed Postsecret admissions in one place, or this Pinterest page where people have collected highly personal Mormon memes—but they seem to be gaining steam.

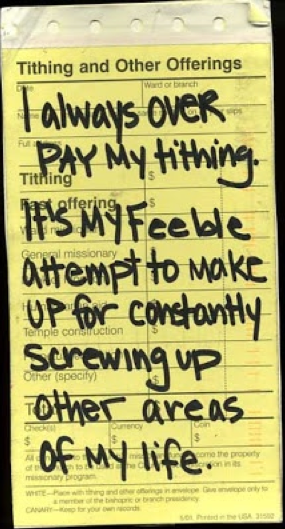

Some are full-on, angry breakup declarations. Others are more subtle and heartrending, showing otherwise faithful people who post personal truths they clearly feel unable to voice at church.

I receive a fair number of letters from those people. What they tell me ranges in severity from mild worries that they can’t measure up to deep anxiety that if anyone at church knew the real person inside of them, they would be shunned.

I receive a fair number of letters from those people. What they tell me ranges in severity from mild worries that they can’t measure up to deep anxiety that if anyone at church knew the real person inside of them, they would be shunned.

Contemporary Mormonism’s don’t-ask-don’t-tell approach makes sites like Post Secret particularly attractive since we no longer have a rite of public confession.

We certainly have private, ecclesiastical confession; penitent Mormons can and should take some sins before their bishop. There are also opportunities to counsel with the bishop at a temple recommend interview or tithing settlement.

But public confession in which Mormons air their dirty laundry before God and everybody? Unless some individuals choose to do so during open mike at a monthly testimony meeting, public confession is a relic of the Mormon past.

According to an excellent BYU Studies article by Edward Kimball, many nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints came clean before their congregations. The practice waxed and waned, gaining momentum during some periods (such as the Mormon Reformation) and becoming less common in others.

Not everyone was a fan of transparency. Brigham Young, for example, thought the Saints should keep themselves to themselves:

Were I to relate here to you my private faults from day to day, it would not only do you no good, but it would injure you. If you were to relate your private faults to one another, it would tend to injure you; it would weaken and not strengthen either the speaker or the hearer, and would give the enemy more power. Thus far, I would say, we are justified in what some call dissembling. . . .

I have my weakness, and you have yours; but if I am inclined to do that which is wrong, I will not make my wrong a means of leading others astray. Many of the brethren chew tobacco, and I have advised them to be modest about it. Do not take out a whole plug of tobacco in meeting before the eyes of the congregation . . . . If you must use tobacco, put a small portion in your mouth when no person sees you, and be careful that no one sees you chew it. (JD 8:361–62, March 10, 1860)

On the one hand, I can see Young’s very practical point that we can’t take up everyone’s time with a litany of all our wrongdoing. He separates peccadilloes that are personal “follies” (in his day, not keeping the Word of Wisdom was considered such) from sins that actively injure others.

Fair enough. But I hate it that words such as “be careful that no one sees you” create a false culture, encouraging masks to the point that we are considered justified in “dissembling,”—i.e., putting on a good show. Young actually counsels people to screen their imperfections from each other, even to the point of sneaking off in secret: “hide it from the eyes of the public gaze as far as you can, and make the people believe that you are filled with the wisdom of God.”

I don’t agree that public confession weakens the confessor or the hearers. On the contrary; it’s the perpetuation of a masquerade that causes lasting harm.

We need more public confession in the LDS Church, not less.

Now, I’m hearing an objection in my head from those who already feel judged by the Mormon people; the last thing they want is to make themselves vulnerable before the very community they’ve come to regard as judge, jury, and executioner. And perhaps they are right that some critics would take advantage of their moments of defenselessness.

But surely in God’s timing there are also other cases where they would see their judges become vulnerable too; where the community could be brought closer by having pain and failings out in the open; where we could chip away at the myth of perfection and see the church as it really is: a community of flawed and wounded people in need of holy grace.