Many of atheism’s most visible public advocates are white men. So it isn’t surprising that a number of people struggle with conversations about the intersections of race, ethnicity, and nontheism—if they participate in such discussions at all.

Fortunately, some atheist organizations and individuals are working to advance these discussions, from the Blackout Secular Rally and Day of Solidarity for Black Non-Believers to writers like Sikivu Hutchinson.

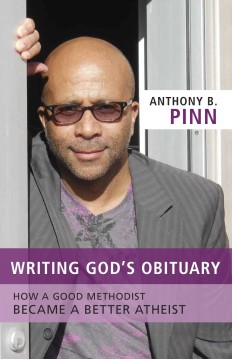

Among those at the forefront of these efforts is Dr. Anthony B. Pinn, a leading scholar and public intellectual who has done a great deal of work on issues relating to Black nontheism. The Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor of Humanities and Professor of Religious Studies at Rice University, Pinn also serves as the director of research for the Institute for Humanist Studies.

The author and editor of thirty books, his latest is Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist. I spoke with him about why he wrote a memoir, discussions about race and ethnicity among nontheists and how they can improve, the priorities of the atheist community, and what he thinks of his childhood religious beliefs.

Chris Stedman: Writing God’s Obituary tells your personal story. Why did you write it in this way?

Dr. Anthony Pinn: I’ve reached a point where I feel the need to think back on my life—how I’ve gotten to where I am—and in part this look at the past is my effort to gauge my present and think through the tasks ahead of me. I wanted to take an opportunity to think more fully through my move from theism to atheism.

I think there’s something to the W. E. B. Du Bois sense that we tell the story of larger communities in part by telling the story of the human we know best. So I also decided to write my personal story as a way to get a more graphic sense of the growing African American humanist communities, and to do that in a humanizing way.

CS: This book tackles diversity issues in Unitarian Universalism, in Humanism, and among nontheists. Can you say more about these issues, and how they’re being addressed—or how they should be?

AP: As I moved deeper into my humanism I felt a need for something resembling community. I was encouraged to give the Unitarian Universalist Association some attention. While I appreciated how welcoming people were, there was great deal of ignorance regarding why African Americans are theists.

Some of it was racism, but much of it was simply uninformed opinion that I couldn’t accept from people who considered themselves enlightened and knowledgeable. I find much of the same rhetorical commitment to diversity and difference within the humanist and atheist movement—and much of this involves a misguided assumption that difference is a problem to solve rather than seeing difference as a creative tension to nurture and maintain. People calling for diversity often want more shades of the same: we will welcome others in, but we don’t want to change anything about the range of issues we address and how we conduct our business.

It’s possible that some of what has frustrated me about responses to diversity within the humanist and atheist movement results from a lack of information concerning the history of African American humanists and atheists. And maybe there’s some merit to telling that history, one humanist and atheist at a time.

CS: Can you speak to the current state of discourse about nontheism and race, ethnicity, and social justice?

I think discourse regarding race, ethnicity, and social justice amongst nontheists too often reflect the larger national conversation. That is to say, it often lacks depth and at too many points doesn’t move beyond easy rhetoric.

There are, of course, examples of discourse pushing beyond easy exchange—but it hasn’t gone far enough. As I see it, issues of diversity for nontheistic organizations are often presented through the presentation of heroic or grand figures within “marginal” communities. So, for example, billboards celebrating heroic African American humanists combined with current African American figures.

While this speaks to the important historical presence of diversity regarding nontheistic thought, I believe more attention should be given to exposing the work done by diverse communities as opposed to just stating the presence of a diverse nontheistic community.

Within nontheistic circles, this is often a result of tunnel vision regarding what are considered the important questions and issues: science education and separation of church and state. While these are important, they don’t provide a good sense of all the other challenges and concerns that nontheists should address. For humanists a full range of social concerns ought to mark our efforts: anything related to the flourishing of life should be within our wheelhouse.

CS: What’s the significance of this book’s title?

AP: For me the title is a way of capturing the decline and eventual death of a concept—God—that had been important to me for years. I wanted the title to reflect my transition from theism to nontheistic humanism through my push away from God—God being the central category of my religious youth.

The title also reflects my effort to point out that this movement to atheism didn’t involve anger. But instead, the use of “obituary” in the title is meant to point out a more balanced and appreciate approach. I don’t hate my former life; I have simply moved beyond it.

CS: You were religious as a child. What do you think of your childhood beliefs?

AP: Thinking back on those years, I understand the type of security, place, and expression of love that my religious commitments and religious family provided me. As James Baldwin said regarding his own religious youth, you have to belong to something—and for him it was the church. For me, it was the church. It smoothed over the rough patches of life.

Now I appreciate that that smoothing over came with a price, and that it ultimately did me little good. I don’t hold to any of those old theological and religious beliefs and doctrines; but I don’t think back on them with a sense of shame. I was what I was—for many reasons—and I now am what I am for better reasons.