A Fulbright scholar contends that animal suffering presents a formidable challenge for creationists and Biblical literalists. – Image courtesy of Intervarsity Press

Christian creationists contend that suffering and death entered the world after the first sin recorded in Genesis 3. But what about animals–specifically those designed for predation? Doesn’t animal suffering contradict the traditionalist teaching?

Ronald Osborn, in his book Death Before the Fall: Biblical Literalism and the Problem of Animal Suffering, surveys the animal kingdom to critique the literalism of “scientific creationism” and wrestle with questions of divine goodness. A 2015 Fulbright scholar and postdoctoral fellow Wellesley College, Osborn’s ideas are creating quite a stir. Christianity Today called his book, “a full-bore, unflinching assault on literalism in biblical interpretation, particularly in regard to the first chapters in Genesis” and added, “a simple assertion that anybody who believes as Osborn does cannot believe in the Bible will not do.”

Here, we discuss his ideas and how he believes they create problems for creationists.

RNS: You say there is a theological problem with animal suffering.” Explain.

RO: The problem of animal suffering is similar to the problem of human suffering: How could an all-loving and all-powerful God permit innocent creatures of any kind to experience pain, including prolonged agony, for no fault of their own?

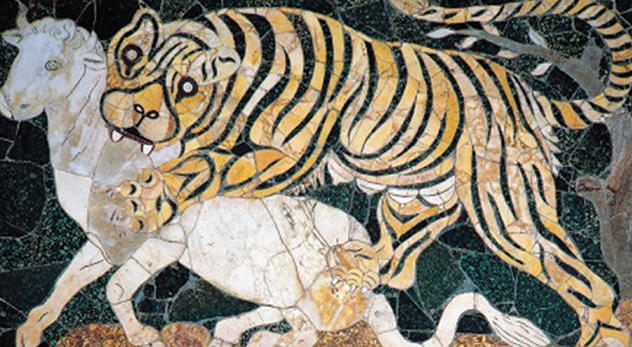

In the case of animals, however, there are additional theological challenges. What are we to make of creatures that by every indication are perfectly “designed” for predation–lions, crocodiles, and Great White sharks? Did God make them this way in the beginning? Did he “curse” or supernaturally modify the animal kingdom after Adam and Eve’s fall? What are the implications of this idea for our understanding of God’s character? [tweetable]Is God only responsible for those parts of the creation we are comfortable with?[/tweetable] What about those that raise perplexing and perhaps insoluble riddles about divine goodness and love?

RNS: Do you think this problem is more difficult for young earth creationists than for someone like you, a Christian evolutionist?

RO: I have never been comfortable with the label of “Christian evolutionist” since the word “evolution” has come to be weighted with so much historical baggage. I am not an “evolutionist” if you mean someone who subscribes to what has been called ultra-Darwinism or philosophical naturalism in theological disguise.

As a Christian who takes the witness of Scripture very seriously, I have come to accept that God’s ways of creating include not only dramatic events but also what we have come to think of as “natural” processes that include a great deal of creaturely freedom or agency, wildness, and indeterminacy in the universe. This does not answer all of the pressing theological questions that arise from the realities of animal suffering, and it raises some new ones, but such an understanding of the creation makes better sense of the biblical and the scientific evidence than the alternatives.

RNS: What about people who say that there was probably no animal death before the fall, that the “lion laid down with the lamb,” so to speak, because this is what God originally intended? Does that defang your argument?

RO: The Isaiah passage about lions laying down with lambs hints at a future eschatological horizon in which peace is brought to the animal kingdom. However, it says nothing about the character of the creation from the beginning. The clearest biblical statement on the question of animal ferocity as part of God’s creation comes in the final chapters of the book of Job when God speaks from out of the whirlwind. The theology of creation developed in Job is radically non-anthropocentric. The Creator glories not in lions that have been defanged but in lions on the hunt, in fierce eagles, and in the Behemoth and the Leviathan.

RNS: Do you think plant death before the fall presents a problem? It is, after all, still death.

RO: We could take the question a further step down to the cellular level and basic metabolism. I am not committed to defending the idea of a deathless creation when it comes to animals with complex nervous systems that are capable of experiencing pain, so clearly I have no stake in defending a static, deathless view when it comes to plants or other non-sentient organisms. In fairness to strict biblical literalists or young earth creationists, many of them recognize this problem and would also allow for plant death as a necessary part of creaturely existence.

RNS: Why did you devote so much of your book to talking about Biblical literalism? Is literalism and your view mutually exclusive?

RO: The book is not a systematic theological treatment of the problem of animal suffering, but rather a somewhat eclectic gathering of essays and reflections on the perils of rigid literalism with particular attention to the animal suffering problem. I have no agenda to turn creationists into evolutionists but I do hope this book might help to open a space in which Christians raised in highly literalistic, if not fundamentalist, traditions can wrestle more honestly with questions of religion and science. I have therefore tried to distinguish between literal readings of Genesis and rigid forms of biblical literalism, since I do think there is a difference. My own grandparents, for example, read Scripture in a very “plain”, literal manner but without succumbing to the exclusionary and dogmatic hyper-literalism that is the real target of my book.

RNS: What about Intelligent Design (ID) theorists? How do they respond to you?

RO: I hesitate to comment on ID theory because it represents such a broad coalition. Insofar as ID theorists have engaged in a purely negative critique of naturalism, I have benefitted from their work. Insofar as some ID theorists have attempted to scientifically prove the necessity of a Designer through arguments from irreducible complexity, I find their project deeply problematic.

No matter how different they might be in scientific rigor and sophistication both ID theory (in this latter form) and creationism appear to me to share the same thoroughly modernist philosophical assumptions and theological anxieties. Both strive to answer the challenges of scientism on scientism’s own terms by providing us with an empirically verifiable foundation for our beliefs. Instead of attempting to debunk ID theory as failed science by guilt of association with young earth creationism, I would invite people to think through the theological implications of an ID theory that scientifically succeeds.