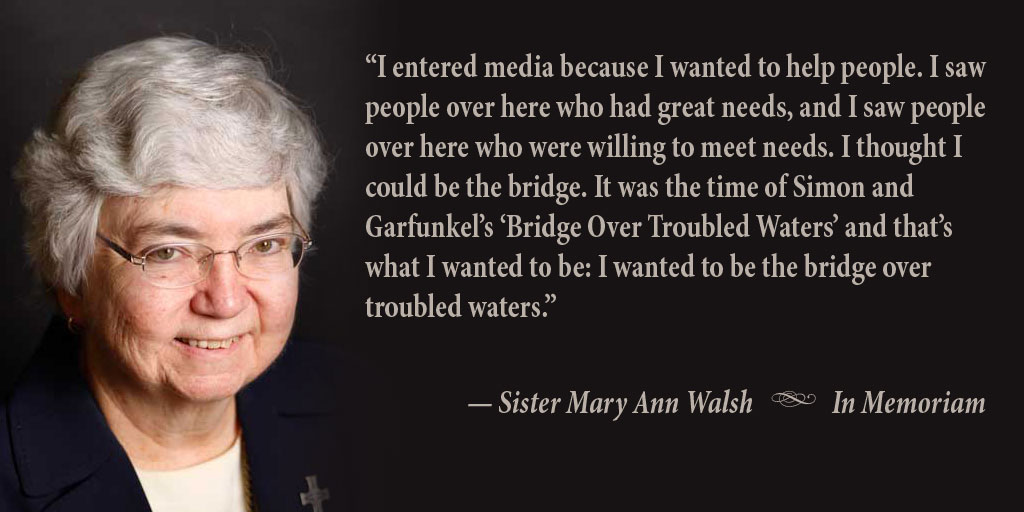

(RNS) Sister Mary Ann Walsh was director of media relations for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Religion News Service file photo courtesy of U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

NEW YORK (RNS) Sister Mary Ann Walsh, a quiet nun with a keen wit who led a very public life as a journalist and a longtime spokeswoman for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, died on Tuesday (April 28) after a tough battle with cancer.

She was 68 and passed away in a hospice in Albany next to the regional convent of the religious order she entered as a 17-year-old novice in 1964.

Walsh had moved to her native Albany from Washington last September after it was discovered that the cancer that had been in remission since 2010 had returned.

She was able to receive better care there and live out her days with other members of the Sisters of Mercy. She was transferred to the hospice on April 23 as her condition deteriorated.

“Sister Mary Ann,” as she was known to the many journalists she sparred and joked with and, with regularity, befriended, worked at the communications office of the American hierarchy for 20 years, retiring in the summer of 2014 just before she fell ill again.

She became director of media relations for the USCCB — the first woman to hold that position — after coordinating media for World Youth Day in Denver in 1993, which featured an enormously successful visit by then-Pope John Paul II.

That period of especially positive salience for the Catholic Church soon gave way to fraught years marked by growing internal divisions among the bishops and then, after 2002, the explosion of the simmering clergy sexual abuse scandal.

The election of Barack Obama in 2008 and battles between the White House and the bishops over health care reform and other issues also left Walsh and the hierarchy’s communications apparatus scrambling to respond to controversies.

Moreover, the role of “spokesperson” for the USCCB has always been a term of art. Bishops like to serve as their own spokesmen and deliver their own message, rather than delegating that role to a national official, so trying to craft a coherent message and deliver it in a timely and effective manner was challenging for Walsh and her colleagues.

Still, if it was a tough job, and often a frustrating one — Walsh joked privately that her service at the USCCB would cut years off her time in Purgatory — she did her job faithfully and effectively.

Religion News Service graphic by Tiffany McCallen

She was a straight shooter who wasn’t shy about letting journalists know when she thought they got a story wrong, and explaining just how wrong they had been, and suggesting how they might get it right the next time. This was done quietly, however; Walsh was at heart a private, almost shy person who was loath to draw attention to herself, or embarrass others.

Walsh was also respected because she had worked both sides of the journalism business.

She was born in Albany and as a high school student had been drawn to the Sisters of Mercy and their commitment of service to the poor, especially women and children.

Walsh entered the order during a period of great social upheaval in American society and in U.S. Catholicism after the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, and she was joining religious life just as many priests and nuns and brothers started leaving.

Apart from her passion for the marginalized, Walsh was a gifted writer — she earned a master’s degree in English from the College of St. Rose as well as a master’s degree in pastoral counseling from Loyola College of Maryland — and she began her journalism career at the Albany diocesan newspaper, The Evangelist.

“I entered media because I wanted to help people,” Walsh said earlier this year in a video posted by her community. “I saw people over here who had great needs, and I saw people over here who were willing to meet needs. I thought I could be the bridge. It was the time of Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ and that’s what I wanted to be: I wanted to be the bridge over troubled waters.”

She was also good at the nuts and bolts of journalism. For instance, in the 1980s when the popular TV host Phil Donahue was pushing for coverage about his essay on the nuns who taught him in grade school, Walsh did some digging and found out those sisters were inventions. Donahue tried to have the story killed, but it ran and went viral.

She later went on to work as a correspondent for Catholic News Service in Rome and Washington before taking the USCCB job. Walsh coordinated media for the U.S. cardinals during the papal conclaves in 2005 and 2013, and she edited books on John Paul II and Benedict XVI. She also produced videos for the USCCB and regularly wrote op-eds in secular media outlets explaining and defending the hierarchy’s positions.

But the constant media battles did take a toll, and Walsh — who was always clear-eyed about the shortcomings of the institutional church even as she sought to mitigate those failings — was especially upset about the Vatican criticism and investigation of the main leadership network of American nuns.

In July 2014, the Jesuit-run America magazine announced that Walsh would leave the USCCB to join the publication as a columnist and blogger.

Walsh was returning to her vocation of journalism and was thrilled at the opportunity, if a bit daunted.

“It’s the ideal job, a job of opinion, after working in an institution (the USCCB) that thought opinion was anathema,” she said in an interview with Catholic News Service in February.

But, she added, “It’s an unusual feeling. … I don’t think of myself as having some great opinion the world is waiting for.”

Just before she left the USCCB she fell ill, and doctors discovered that the breast cancer that had appeared to be in remission since 2010 had returned with a vengeance.

“My oncologist was stunned, my primary care doctor was stunned and I was stunned that I had this aggressive, turbo-charged cancer,” Walsh said later.

In 2012 she had written a tribute in The Huffington Post to the sisters who helped her through her first bout with cancer, and her community once again rallied around her, moving Walsh back to Albany in mid-September last year.

But the nun was not done. She seemed to find her voice even as her body failed. Like so many other Catholics, she had been energized by the election of Pope Francis, whose focus on social justice and mercy mirrored her own pastoral orientation, and over the ensuing months she wrote a number of pointed, and also poignant, columns and blog posts for America.

In March, the Catholic Press Association gave her its highest honor, the St. Francis de Sales Award, which recognizes lifetime achievement in Catholic media.

Walsh’s “extraordinary commitment to pursuing integrity of word and deed through her writing continues even as she shares her personal illness,” Sister Patricia McDermott, president of the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, said at the time.

In one especially pointed column, on the Vatican’s investigation of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, Walsh wrote that the Vatican should “just say ‘Thank you’” to the nuns and end what “may be the most ill-fated controversy ever launched across the Tiber.” (Rome did wind the probe down in April, with an olive branch and apparently little to show for its efforts.)

But Walsh was also, and always, a Catholic of deep faith and devotion, and that came through in her writing, and her characteristic good humor.

Earlier this year, reflecting on her devotion to praying the rosary — sometimes the only task she could manage as she grew weaker — Walsh quipped that the Marian prayer became a serious habit during her commute in traffic in Washington. “I used to say that the rosary was my antidote to road rage,” she said. “You can’t swear and say a Hail Mary at the same time.”

In an account of her illness written by her community, Walsh called her final months “a living wake” as she received prayers and good wishes from so many people she had known through her life, and as she struggled to let herself be taken care of, instead of the other way around.

“I find it hard to receive mercy,” she said in a brief video posted by the Mercy sisters. “I’m used to being independent, and if somebody helps me put on my shoes, for example, that’s humbling. I don’t expect it.

“Mercy has jumped in from every corner to help me, in ways both large and small,” she said. “I want for nothing.”

MG END GIBSON