Morgan Atkinson is already the world’s living expert on “the Thomas Merton documentary.” He’s the filmmaker responsible for Soul Searching: The Journey of Thomas Merton, which was picked up by PBS in 2006, and The Abbey of Gethsemani, an in-depth look at the monastery where Merton spent most of his adult life.

Now, however, Atkinson is zeroing in on Merton’s critical final year, which was also one of the most tumultuous years in American history: 1968. Here we see Merton agitating to leave Gethsemani and engage with the world: specifically, to travel to Asia for interfaith dialogue and a chance to meet the Dalai Lama.

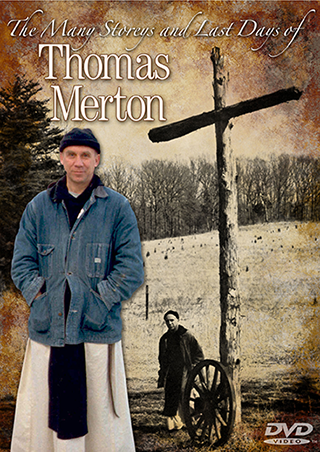

I’m excited to see the documentary The Many Storeys and Last Days of Thomas Merton when it premieres in Cincinnati on Thursday; it’s also one of the highlights of this week’s Festival of Faiths in Louisville, which will celebrate Merton’s 100th birthday. — JKR

RNS: Why did you want to focus on the last year of Merton’s life?

Atkinson: If I could nitpick about the first documentary – and people tend to nitpick at their own work – a shortcoming I felt most keenly was that I didn’t do much justice to that last year of his life, and his going to Asia. That was such a significant event not only for him, but also for people within the Catholic Church and of general spiritual interest. He was one of the pioneers of interfaith dialogue.

Also, I am a child of the 60s, so that year 1968 had a lot of power for me. There were so many significant events, both good and tragic, that happened in that year to shape our country. In a monastery you are to some extent cloistered, but still, all these events going on in our country were things Merton was well aware of. Merton refers to 1968 as a beast of a year. Of course, he wouldn’t have known that his own death would make it a beast of a year.

RNS: Will viewers be in for any surprises?

Atkinson: A lot of people might not be aware of the tension he had within his own monastery with his abbot, with whom he had – I wouldn’t say a love/hate relationship, since there was no real hate there, but maybe love/resentment. The abbot’s job was to run a very structured and orderly monastery, and Merton didn’t always fit into that. It’s not that he was too good for the monastery, but his temperament was so different from the other monks in the community. So when you read his correspondence with the abbot, you see this real tension. So when he finally received permission to go on this trip, it was very liberating.

RNS: So the abbot placed restrictions on Merton’s travel?

Atkinson: Yes. The restrictions should not have come as any surprise to anyone in a Cistercian or Trappist life. They are known for being very cloistered and disciplined. But Merton wanted to travel. He was always being invited to conferences and things of that nature, and the abbot rarely let him go. While James Fox was abbot, he never let Merton go. And some of the other monks at Gethsemani did get to go, and this bothered Merton. You see in his journals that some days he would be really bitterly complaining about it, and then a week later he would say, “Well, I guess I kind of understand it.”

RNS: Merton’s life ended on his trip to Asia at the end of 1968, where he’d gone for interfaith dialogue with Buddhists, including the Dalai Lama. Is that trip discussed in the film?

Atkinson: Yes. One of the interesting things about this documentary is that I got to interview the Dalai Lama about the time that he met with Merton in India in late October or November of 1968. They initially were supposed to have one meeting, and I think they were both a little leery of it. Merton made one remark that he had already met so many officials, and that he was wary of meeting another “suit.” And the Dalai Lama had said, earlier in his life, that so many of the Christians he had met were only interested in trying to convert him to Christianity. So they met with a little bit of their guards up, but it went very well. What was supposed to be one meeting stretched into three. The Dalai Lama was very interested in Western monastic practice, and Merton was very interested in Buddhist monasticism.

When we had this audience last year with the Dalai Lama [for the documentary interview], he just lit up talking about it. And their meeting was 45 years ago. He told someone else that he’d had three great teachers in his life, one of which was Thomas Merton, who had presented Christianity and Western spirituality in a new way.

The news of Merton’s death saddened him very much, and he felt it was a responsibility. He said when you have two people with similar drives and values, if one of them dies, it’s the other person’s responsibility to carry out that work. I must confess to some degree of skepticism about this, but he was so genuine in the way he said it, and the way he just lit up when he talked about Merton. This wasn’t calculated to please our ears, but something he very much meant.