(RNS) When Laila Alawa woke up on a recent morning, her phone wouldn’t stop pinging with Twitter notifications.

“You’re not American, you’re a terrorist sympathizer immigrant that nobody in America wants and for good reason,” one user tweeted.

“This c**t needs to be packed in a freight container, deported+ dumped mid-ocean like the garbage she is,” wrote another. Still others called her a traitor, a terrorist, a pig.

“Five minutes would go by and I would refresh my Twitter, and 20-plus new tweets would have come in,” Alawa, who wears a hijab and runs a Muslim-led feminist media company in Washington, said. “Each one was more hateful than the last.”

Muslim women like Alawa have worked to create a vibrant space for themselves in the online world. But increasingly, many groups — from Islamophobes to conservative Muslims to feminists — are using social media’s anonymity and lack of accountability to pry that from them.

Photo courtesy of Laila Alawa

It didn’t take long for Alawa, 24, to pin down the cause of the firestorm: a single post on a right-wing blog. A writer there had seen her association with a new Department of Homeland Security counterterrorism report, then scoured Alawa’s social media until he found a 2014 tweet that said 9/11 had changed the world “for good.” (The phrase “for good” can, of course, mean “permanently” rather than “for the better.”) The tweet spawned dozens more, including one by leading anti-Muslim blogger Pamela Geller.

The net result: a phone buzzing with thousands upon thousands of inflammatory tweets, Facebook messages, emails, Instagram notifications and more. Most were filled with insults, threats and rants on everything from genital mutilation to Shariah law to comparisons between Alawa and the Orlando, Fla., nightclub shooter. But many came in solidarity, too — from fellow Wellesley alumnae, Muslim American writers and Alawa’s smartphone-armed sisters in faith.

Moving online

In the last decade, young Muslim women have developed a strong digital presence that has paved the way to greater public engagement with the media by way of hijab video tutorials like those of British fashion superstar Dina Torkia, or viral Twitter hashtags like the feminist #YesAllWomen.

“A lot of times Muslim women have no choice but to go to the online space,” said Wardah Khalid, a Middle East policy analyst who spent years writing the Houston Chronicle’s Young American Muslim blog and regularly gets messages calling her a “raghead” or saying she is oppressed. “If you look at some of the traditional institutions that are purporting to speak for Muslims, the vast majority of their boards are male. That’s why Muslim women have taken such a large online presence. They created that space for themselves.”

But as a result, Khalid said, they are dealing with more abuse online than they might get sitting on the board of an organization like the Islamic Society of North America.

Wardah Khalid speaks at “No Way to Treat a Child” interfaith vigil on Capitol Hill on June 1, 2015. Photo courtesy of Emily Sajewski, FCNL

As media and networking have moved online, so has harassment. Earlier this month, The New York Times’ Washington bureau editor quit Twitter, saying the platform had not done enough to combat surging anti-Semitism. About 65 percent of young adults on the web have faced some level of harassment there, according to a 2014 Pew report. The numbers are especially bleak for young women: in a 2016 Australian study, more than 75 percent of women under 30 reported experiencing some form of abuse or harassment online.

The trend holds in the Muslim community. More than 70 percent of verified incidents of anti-Muslim abuse reported to the British organization Tell MAMA (Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks) took place online, and more than 80 percent of online attacks consist of verbal abuse and hate speech. One study participant said she never received any hate on her Twitter account until she began using a photo of herself wearing the hijab as her profile picture. Now, she receives “regular abuse” on the site.

Another participant said she tightened her Facebook privacy settings because of such abuse. For yet another participant, much of the abuse came from the “cyber mob” of right-wing, anti-immigrant English Defence League sympathizers. She reported the abuse to Tell MAMA after trolls threatened her with physical violence and tweeted photos of her with the words “You Burqa wearing slut.”

It wasn’t just EDL supporters. “They come from all walks of life and all backgrounds which is alarming,” one Muslim woman told Tell MAMA researchers. “They will set up a hoax ID and from there they can abuse anyone with complete anonymity and hiding behind a false ID.”

Anti-Muslim perpetrators, who are generally white males aged 15 to 35, often say they’d never attack a woman, Tell MAMA founder Fiyaz Mughal told VICE reporters earlier this year. “But they feel like they can target Muslim women, because they didn’t see them as female. They’ve dehumanized them so much that they can’t see their identity in a gendered way anymore.

“The only thing they see is that they are Muslim.”

Easy targets

Why are visibly Muslim women like Alawa so often targets of harassment online? “Muslim women are the most visible targets, as well as Sikh men,” said Alawa. “Their identities are on a platter for the rest of the world to pick apart.”

In the wake of #GamerGate, a controversial online movement highlighting shocking sexism and harassment in video gaming culture, trolls told one Muslim woman she was too “oppressed” to think for herself and that she “should focusing on ‘freeing’ (herself) instead of calling out #GamerGate’s misogyny.”

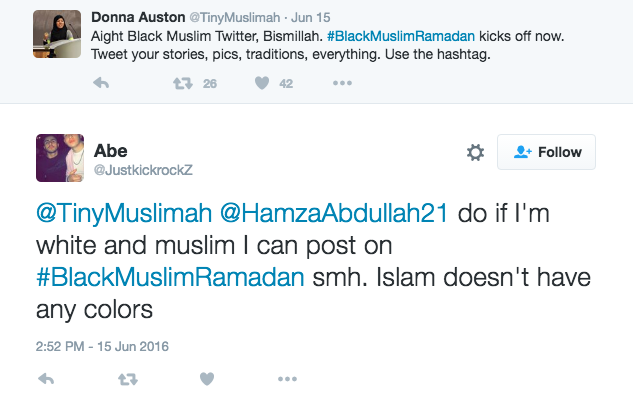

Photo courtesy of Donna Auston

And the more marginalized a person’s identity, the more trolls pile on.

Donna Auston, the 43-year-old creator of the #BlackMuslimRamadan hashtag conversation, knows that well.

She’s known on Twitter as @TinyMuslimah; she tweets often about the intersection of race, religion and activism. Much of her research as a Rutgers University doctoral candidate in anthropology involves monitoring digital spaces to see how social justice issues like #BlackLivesMatter unravel online.

This month, she held the second annual #BlackMuslimRamadan chat. “I’ve had so many Muslims in my Twitter messages and mentions talking about how it’s somehow un-Islamic to say that I’m black or to acknowledge my different cultural practices.”

Race is not the only dividing line. Six years ago, 35-year-old writer Ayesha Noor penned an op-ed for a local Virginia paper about Pastor Terry Jones’ planned “International Burn a Quran Day.” In it, she pointed fingers at the Muslim leadership’s failures, too. So when she started getting hate-filled messages from anti-Muslim readers, she was surprised. “Even if you say what they have been saying — even if you agree with them, you still get hate.”

Noor is no stranger to angry messages. As an Ahmadi Muslim, part of a minority sect declared heretical by orthodox Islam, she fields both standard anti-Muslim trolls as well as those declaring her a “kafir,” or disbeliever. “It’s been a couple years since I’ve stopped responding to people telling me, ‘oh, you are not a Muslim’ or ‘all Muslims are bad,’” she said.

In addition to her personal Twitter account, Noor runs @EqualEntrance, which shows Ahmadi mosques where women have equivalent praying facilities to those of men. The backlash can be broken down into three categories: “You can’t call this a mosque because Ahmadis aren’t Muslim,” “So this is where you come for jihad?” and “This isn’t feminist enough.”

The last one is almost comical. On one hand, she says, many feminists, atheists and self-proclaimed Muslim reformers say Muslim women are second-class citizens. “Then they go after me for saying Muslim women are actually people with their own minds and their own space,’” Noor said. “And they were saying, ‘Oh, but you can’t pray together! And it’s like, ‘But we don’t want to pray together.’ They put words in our mouth.”

Khalid, the Houston-based Middle East policy analyst, has felt the barbs of Muslim reformists, too. In March, she published an article on Vox criticizing the media’s use of what she termed “pseudo-experts” on Islam, and pointing out such names as ex-Muslim Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Muslim Reform Movement co-founder Asra Nomani.

The resulting Twitter backlash from reformists and their supporters was the first time she had ever been targeted on such a personal level, she said.

“They were saying I’m silencing their free speech, they were calling me a tribalist, they were trying to dig up dirt on me,” Khalid remembered. “They would reach out to other journalists who had interviewed me and say ‘hey, do you know this girl you’re writing great things about tried to smear our reform campaign?’”

The messages used to hurt her, she admits. “But then I realized that I’m the one who wrote the article, and I got to say what I wanted to say, and what I said obviously struck a nerve.”

Pushing back

There was a point, about four years ago during a national Ahmadi convention, where Noor was dealing with so many messages from anti-Ahmadi trolls that she considered leaving Twitter.

“When one troll comes, he brings ten trolls with him,” Noor said. “You think you’re talking to a different person and it’s exactly the same one. You only get rid of it when you block all of them.”

She used to reply to as many users as she could, muting those she found abusive, but when one exchange went on for about 200 tweets, she realized: “Maybe I should just stop doing that.” Now that’s she’s quit engaging the trolls, she sees social media as a positive experience, where she can learn about and respond to misinformation about her faith.

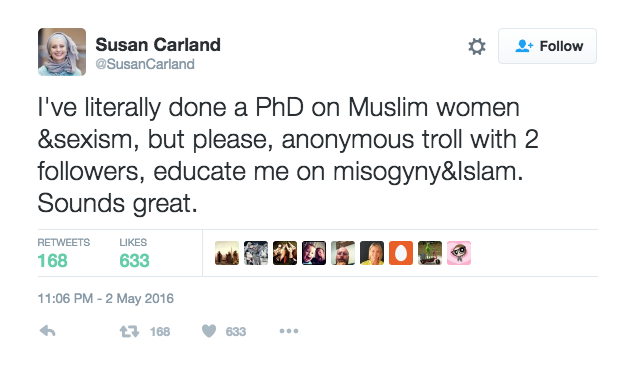

Last year, Susan Carland — a hijab-wearing Australian academic — made headlines with her strategy. “I donate $1 to @UNICEF for each hate-filled tweet I get from trolls,” she wrote in a tweet that quickly went viral. “Nearly at $1000 in donations. The needy children thank you, haters!”

In her three years on Twitter, Auston has developed another strategy: rebut and block. She turns the tables on trolls by retweeting (so that her own followers can deal with the troll as they choose), adding a snarky one-liner, and hitting the block button. She ends up blocking trolls several times a week — during events like the Orlando shooting rampage, it can end up being a daily task.

“We don’t take this stuff seriously until it escalates, but I don’t take any of this lightly,” she says. “People talk a lot about how this is because of the anonymity of the internet or whatever — I’m sorry, but that’s not an excuse. And if you feel empowered under any circumstances to speak to someone in a way that disrespects them or threatens violence, then it’s already a serious offense.”

In a world where anyone can suddenly find herself a victim of doxing — when a malicious hacker finds and publishes private information about someone online, often in an act of vigilante justice — responding to trolls is not always the safest strategy, some say.

Wardah Khalid. Photo courtesy of Christine Letts, FCNL

“If someone’s being hostile towards you and your hijab, a lot of times it’s best to just to walk away,” Khalid says. “I don’t want to further something that will only create more headaches for me or hurt me later on. I have no idea if the legal system is going to protect me or not, and even if it does, then by then it might be too late.”

While anti-Muslim attacks are nothing new, legal protections from online versions are limited. Both laws and law enforcement are often unequipped to deal with digital forms of harassment. When Alawa called Washington’s non-emergency hotline, the police didn’t seem to understand that tweets could be actual death threats. “I don’t get what’s going on but I’m trying to understand,” Alawa recalled the policewoman telling her, in disbelief.

“I just sat there and felt kind of deflated,” Alawa said. “It’s 5 a.m., you’re barely keeping it together and you have to explain this to someone who’s supposed to protect you.”

The social platforms themselves can be dangerously slow to respond. When a Twitter account purporting to be Alawa sprung up tweeting racist and homophobic statements, Twitter took more than a day to remove it and publicly verify her real account.

In its 2015 report, Tell MAMA researchers said it is critical for social media companies like Twitter and Facebook to make their systems of reporting hate crimes and online more user friendly. The organization recommended adding distinct tools aimed at reporting incidences of bigotry, hate speech and prejudice. Several study participants told researchers that the companies were either slow to act or ineffective, as perpetrators simply changed their names and made multiple accounts.

“I don’t think that Twitter has set up proper safeguards for people to feel as though there is some sort of community,” Alawa said. “Honestly, I wish Twitter understood what it means for someone to start tweeting out false rumors about me and start taking those threats seriously.”