WASHINGTON (RNS) — When Mitt Romney announced his campaign to become Utah’s next U.S. senator, he drew a stark contrast between the accomplishments of the state he wants to represent and those of lawmakers in the nation’s capital.

In a slick 2-minute video released Friday (Feb. 16), the former Massachusetts governor and onetime GOP presidential candidate pointed to how the state exports more than it imports, balances its budgets, and embraces immigrants — things, he said, national politicians fail to do.

“On Utah’s Capitol Hill, people treat each other with respect,” Romney, already an overwhelming favorite, declared in a possible swipe at President Trump’s insult-ridden style of politics. “Utah is a better model for Washington than Washington is for Utah.”

But there was one difference he didn’t mention: the prominence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah, where 55 percent of the population claims the faith — including Romney.

That, experts say, likely isn’t an accident, nor does it make him any less Mormon. If anything, it’s one of the most Mormon things he could have done.

Romney’s pitch reflects a Mormon tradition of polite politics and reservedness about one’s faith that differs from other American religious conservatives, in particular evangelicals.

And his campaign is shaping up to be a battle for the soul of Republican Mormons in Utah and beyond, potentially pitting the former governor against Trump and his supporters. But political observers say Romney is tapping into a long tradition of Republican Mormons in the Beehive State to offer an alternative to Trump’s new breed of politics.

Much has been written about how Mormons — the most reliably Republican major religious group in the United States — have been unusually slow to warm to Trump compared to other Republican presidents. Although a recent Gallup poll showed that more than 60 percent of the group approves of the president, experts argue that should be much higher, and Trump only secured 45.1 percent of the vote in the state during the 2016 general election — enough to win, but nowhere near the 72.8 percent Romney secured there when he ran in 2012. This resistance has endured: LDS church officials remain vocally supportive of immigrants in ways that sometimes contrast to Trump, and a 2017 PRRI survey found Republicans who identify as “Never Trump” are significantly more likely than other subgroups to be Mormon.

Romney, for his part, has been openly critical of Trump since the early days of the 2016 election, telling attendees at a Hinckley Institute of Politics forum during the campaign that Trump “has neither the temperament nor the judgment to be president” and that his policies would lead to a recession and “make America and the world less safe.” He has continued to blast the president since his election, demanding in 2017 he apologize for asserting that “both sides” were to blame for the racist violence in Charlottesville, Va.

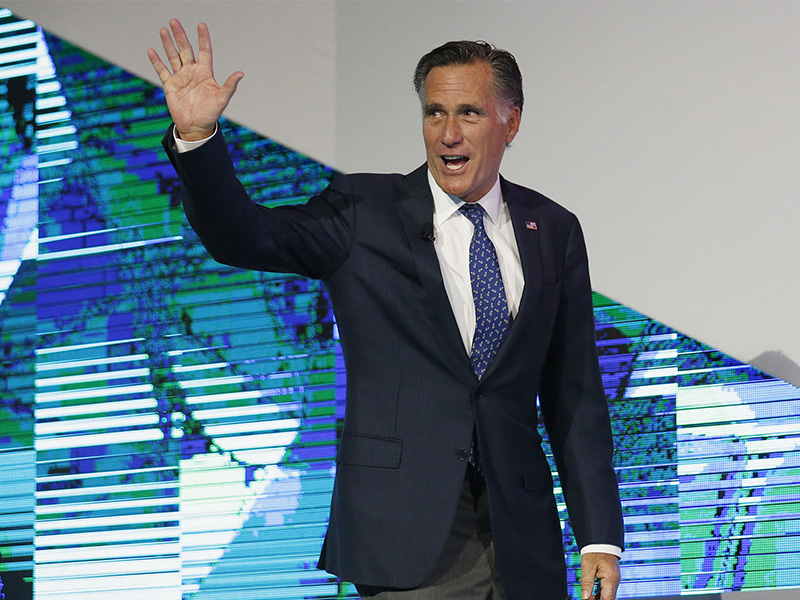

Former Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney waves after speaking about the tech sector during an industry conference in Salt Lake City on Jan. 19, 2018. Romney announced his Senate candidacy on Feb. 16, 2018. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

In Mormon circles, he’s in good company. The LDS church itself took the rare step of issuing a statement in December 2015 implicitly condemning Trump’s proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country. More recently, Mormon Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., delivered a speech from the Senate floor in January condemning Trump’s attacks on the press, concluding by invoking “Oh Say, What is Truth” — an old Mormon hymn.

Taken together, a perception has emerged that while Mormons continue to skew conservative, many remain uncomfortable with Trump — something Romney could capitalize on.

“Mormons have a reputation, and I think mostly rightly, for being generally polite and clean-cut and straight-laced — and none of these things are things Donald Trump embodies,” said Jessica Preece, associate professor of political science at Utah’s Brigham Young University. “There is a style issue that is distasteful to Mormons who are socially conservative and appreciate more traditional ways of doing politics.”

But Utah political observers say they don’t expect Romney, who served for years in Mormon lay positions such as bishop and stake president, to make a big show of his faith on the campaign trail — a posture that is, ironically, deeply Mormon.

Boyd Matheson. Photo courtesy of Sutherland Institute

Boyd Matheson, who recently ended his tenure as president of the Sutherland Institute, a Utah-based conservative think tank, said Republican voters in the state who belong to the LDS church prefer candidates who show their Mormonism through their actions, not their words.

“People want to know your principles and your values, but … if you’re perceived as leveraging your position in the church or affiliation with the church, that is a real turnoff,” said Matheson, who now works as an opinion editor at the LDS-owned Deseret News. “If you have to declare it, you’re not it — that’s sort of how it plays here. It’s much more of a ‘by their fruits ye shall know them’ kind of state.”

Some have highlighted the tradition’s history as a minority faith to explain this accommodating spirit.

But Kathleen Flake, professor of Mormon studies at the University of Virginia, explained the Mormon tendency to be “emphatically neutral” about faith grew out of a controversy in the early 1900s over an earlier Mormon senator from Utah, Reed Smoot.

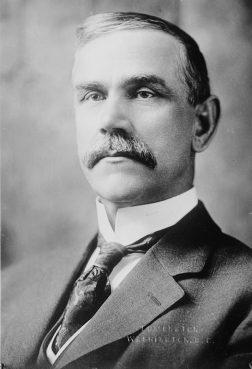

When Smoot, who was also an apostle in the LDS church, was elected, he was beset with accusations such as being too closely tied to the church or being a polygamist — a practice the church formally abandoned years before. Lawmakers convened a series of congressional hearings to determine his ability to serve and called a number of witnesses, including then-LDS President Joseph F. Smith.

Reed Smoot served as a U.S. Senator from Utah from 1903 until 1933. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

“They worked out a particular stance with the federal government in the early 20th century and they’re sticking to it,” Kathleen Flake said. “It’s basically, ‘You obey the law, you act for the common good, and you show tolerance to everybody else — you don’t get in the way of others.’”

The vote to unseat Smoot ultimately failed, and he went on to serve in the Senate from 1903 to 1933 and become influential in the Republican Party. But the UVA professor said the process cemented a certain posture for Mormons when it comes to politics — one that Romney is likely to emulate in ways that set him apart from the president.

“(Many) Mormons finally found a Republican they don’t like — and that’s Trump,” Flake, who wrote a book on Smoot, said.

Preece echoed the notion that Romney’s embrace of this traditional stance is suddenly radical in 2018, as it offers a direct contrast to Trump.

“That’s where the Mitt Romney race is really interesting for Utah: If he holds the line on the traditional Republican — sort of business Republican — perspective, that gives an alternate leader to follow (for Republicans),” she said. “Because Mitt Romney is widely trusted — not exclusively, but is widely seen as an admirable person — the stances that he takes are likely to deeply shape Republicans in Utah.”

Some Utah insiders wonder if Romney’s end goal — assuming Republicans manage to keep control of the Senate this year — is to become majority leader, allowing him the posture of a direct alternative to Trump from the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Still, experts say Romney will likely keep the race Utah-focused, concentrating on local issues such as public lands, education, and air quality. Romney is already facing blowback from fellow members of the GOP for this stance on Trump: Utah Republican Chairman Rob Anderson blasted Romney in a Salt Lake Tribune interview on Wednesday ahead of his announcement, saying, “he has never been a Trump supporter.” (He later walked back his remarks.)

What’s more, Jason Perry, director of the Hinckley Institute of Politics, said that Utah is not exclusively Mormon, and Romney likely wants to court non-LDS members as well.

Even so, he acknowledged appeals to local issues often overlap with Mormon interests.

“Utah does see itself as being a major international player — not just from the business perspective, but because the LDS church sends people all around the world on missions,” he said.