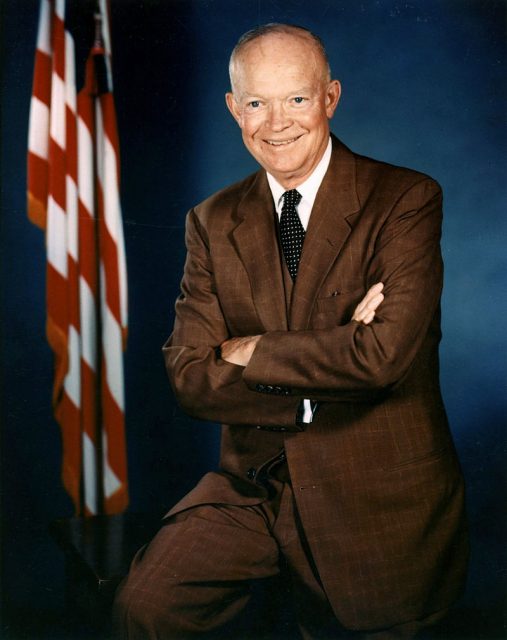

You can still get a chuckle when you quote Dwight Eisenhower’s remark, “[O]ur form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” But what he said next makes clear that his point was not that some religion, any religion, is good for America.

With us of course it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with all men are created equal.”

Ike was saying that democracy (our form of government) depends on a fundamental religious belief in human equality—a debatable proposition perhaps, but hardly a trivial one.

The remark, from a speech he gave shortly after his election as president in 1952, bespoke the country’s mid-century anti-totalitarian project. America had helped defeat Nazism and Fascism in Europe, Japanese imperialism in Asia, and was now engaged in a struggle with Soviet communism—all in the name of democracy and its values.

Religion was part and parcel of the project, not just as a freedom to be defended but as essential to the nature of our form of government.

In 1950, for example, the editors of the Southern Baptist periodical Commission justified promotion of democratic values in their missionary work by declaring, “Political democracy is a by-product of Christianity. It has its roots in the Christian concept of the God-given dignity of every human being.”

That statement is quoted in Saving Germany, James C. Enns’ excellent new book about Protestant missions to Germany in the postwar period. Enns shows how these missions, whether ecumenical, denominational, or revivalist, all put their shoulders to the cause of building democracy in a country that had to be at once denazified and made into a bulwark against the Communist threat.

Today, democracy is again on the ropes. The Führerprinzip is alive and well, and not only in Russia and China, in Turkey and the Philippines. Populist parties across Western Europe declare their admiration for strongman government. The leader of the United States is enamored too, musing the other day about how the U.S. might, like China, think about a life term for its president.

Where Billy Graham once used his crusades to warn against the Soviet threat to democratic values, today his son Franklin celebrates Russian dictator Vladimir Putin as a defender of traditional ones. Nor is Franklin alone among his Christian tribe.

It’s easy to make fun of America’s Cold War religious rhetoric, to disdain it as an unholy subordination of the spiritual to the nationalistic. But with democracy under more serious threat than it’s been since the 1930s, it’s hard not to feel some regret for the passing of that old time civil religion.