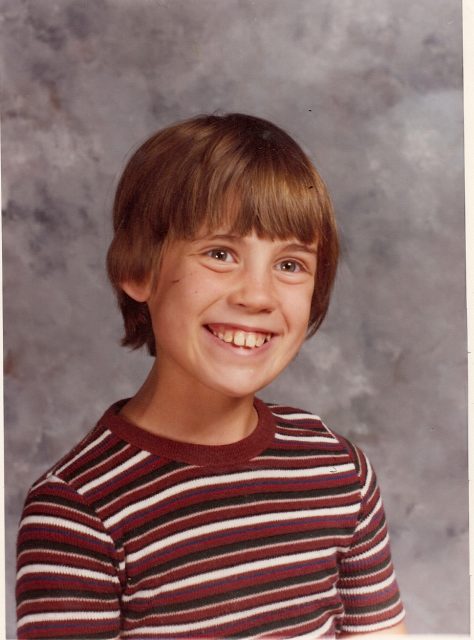

Guest blogger Mette Harrison in 1979.

A guest post by Mette Harrison

This photo shows me as I looked in fourth grade. At age nine, I made a conscious decision to masquerade as a boy as much as possible, mainly at school, because I hated being a girl. Specifically, I hated being a girl in the Mormon world. I’m aware that this evaluation at my young age lacks nuance, but I also think that it showed some keen observance of differences in opportunities in Mormonism.

What I saw as a nine-year-old was that in church, many of my interactions with women were corrections about things I was doing wrong, ways I wasn’t being a proper girl.

I didn’t do my hair and nails properly. I sat “wrong,” with my legs spread apart, forgetting that my underwear showed when I didn’t cross my legs. I hated fancy shoes and tended to wear sneakers to church if my mother didn’t notice (she had ten other children to worry about).

I got stains on my clothes, sang too loudly, talked too much. I answered all the questions and didn’t let anyone else have a chance.

Now, I could chalk most of this up to what has turned into an adult diagnosis of autism, but I think it was more than that. While autism has certain social disabilities, it also has some wonderful aspects that allow me to see through social expectations to deeper issues, including the lack of respect for women and girls that permeates almost all patriarchal cultures.

Mormonism is not exempt.

From my child’s perspective, boys didn’t have to wear uncomfortable dresses because they were supposed to look “pretty.” Boys didn’t have to cross their knees. Boys weren’t hushed and told to let other people have a chance to speak.

Boys learned that they were going to get the priesthood when they turned twelve. Boys got to pass the sacrament. Boys went on missions. Boys stood up and conducted meetings. I saw clearly even at that young age that women were invisible to the power structure of the church.

So that year, I asked my mother to cut my hair as short as a boy’s, and she obliged. She thought that all she was doing was giving me a “practical” haircut. Then I asked if I could get new clothes for school and for my birthday, which was at the beginning of the school year. My mother insisted we shop at Sears because their clothes were durable and affordable. That was fine with me. After we looked at the impractical girls’ section, I directed her to the boys’ section and collected corduroy pants and dark-colored shirts. My mother was glad to get them because they’d be easier to keep clean.

Because we had just moved and my name was mangled in translation, I became “Ette,” which I told everyone at my new school was pronounced “Eddie.” For the next several months, I had a chance to see what it was like to be a boy at school. I got to play rough and tumble and say gross things, and there was no stigma.

I can’t say that in the end, I wanted to stay a boy. It turned out there were things boys couldn’t do that I’d taken for granted as a girl: play jacks, give hugs, cry, and have close emotional friendships. At the end of fourth grade, I went back to being a girl and grew out my hair. In fifth grade, it was no longer a question since I started growing breasts and was obviously a girl.

But the experience lingered in my mind and I suppose I became a budding feminist, even if I’d have rejected that label.

I asked questions in church in my teen years about what it meant when people talked about “the path to the celestial kingdom” when what was described was a purely masculine path. All the examples given were of men, either in the scriptures or in church leadership.

Did you have to have the priesthood to become like God? Did you have to serve in a leadership position? Did you have to serve a mission, love scouting, and wear a white shirt and tie? Often, I was told to be quiet (again), that I took up too much time with my silly questions. I was told that of course there was a slight difference for women, but that it didn’t matter.

But it did matter. It mattered to me that we rarely talked about the women’s path, even in Relief Society. We lionized male church leaders, but didn’t seem to have the same view of female leaders. Be like these men, we were told. But don’t be like men. Be women. It was honestly quite confusing.

Because of all this, I think I saw gender roles as precisely that—roles people play, not inborn qualities that are attached to one sex or another.

As an adult, I see some “updates” on the roles of women in the church, but many of the same strictures that frustrated me as a child. The emphasis on women looking a particular way seems obvious in images of women in leadership who seem to wear similar outfits and even have similar hairstyles and makeup.

I hear less about the sole purpose of women being child-bearing and child-rearing, but when Mormon women quote leaders, they are male authorities. I’ve watched as feminists in the church push for more talk of “Heavenly Mother,” but am honestly not sure that this is any help if Heavenly Mother’s just refashioned in the same image of a caretaking, submissive, “proper” woman.

That was what I wanted to escape from at age nine anyway.

Also by Mette Harrison:

Also by Mette Harrison: