Rwandans sing and pray at the Evangelical Restoration Church in the Kimisagara neighborhood of the capital, Kigali, Rwanda, on April 6, 2014. Rwanda’s government closed hundreds of churches and dozens of mosques in 2018, as it seeks to assert more control over a vibrant religious community whose sometimes makeshift operations, authorities say, have threatened the lives of followers. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

NAIROBI, Kenya (RNS) — After closing more than 700 churches and some mosques in March, Rwandan government officials have moved to institute guidelines for how faith groups operate in the majority-Christian East African country.

Rwanda’s minister in the office of the president has brought to Parliament a draft law that would require Christian and Muslim clerics to attain university education before preaching in churches or mosques. The law would require clerics to have a bachelor’s degree and a valid certificate in religious studies. It would also bar clergy who have been convicted of crimes of genocide, genocidal ideology, discrimination or other sectarian practices.

“I agree with the law. Some of our church groups have been operating in a dangerous manner,” Evalister Mugabo, bishop of the Lutheran Church in Rwanda, told Religion News Service.

Churches and mosques would also be required to institute an internal disagreement resolution body to complement the work of their umbrella organizations and the government’s dispute resolution authority, which resolves conflicts involving different faiths.

The measure, according to government officials, will bring order among churches, some of which are suspected of misleading people.

Judith Uwizeye, minister in the office of President Paul Kagame, presented the draft law. “Everyone would wake up in the morning and call people to start a church. Setting up a faith-based organization didn’t require anything. We want to bring about better organization on the way faith-based organizations work,” she is quoted as saying.

The draft law received wide support from most legislators in Rwanda’s Parliament. It will move to the committee stage, after which it will be brought back to Parliament for endorsement.

In 1994, the country about the size of Maryland witnessed a genocide that left an estimated 800,000 ethnic Tutsi and moderate members of the Hutu tribe dead. Years later, senior church leaders were among those accused of killing citizens or aiding in their deaths and were arraigned before the International Tribunal for Rwanda in Arusha, in nearby Tanzania.

Despite its dark past, Rwanda, like many African countries, has witnessed an upsurge in churches in both urban and rural areas. But in March, its government took a radical move, shutting down hundreds of them in the capital of Kigali.

The action was replicated in other towns, amid support from some religious leaders and criticism from others. The authorities said the churches lacked basic infrastructure, security and hygiene and were contributing to noise pollution.

Those most affected by the shuttering were small Pentecostal churches. Jean Bosco Nsabimana, founder of Patmos Church, a Pentecostal congregation, questioned why government officials had not targeted bars and nightclubs.

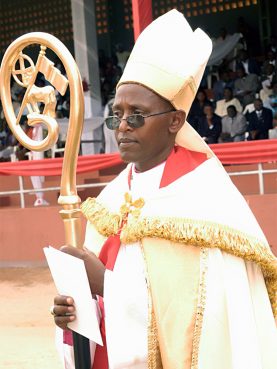

Evalister Mugabo, bishop of the Lutheran Church in Rwanda. Photo via Evalister Mugabo Facebook

But other religious leaders see wisdom in the government move. “Churches are mushrooming too quickly and are exploiting poor people. If they are not controlled, more and more will continue to come up,” said Innocent Maganya, head of the department of mission and Islamic studies at Tangaza University College. “They are being started for personal gains, not for that of the followers. Without discrimination, a bit of sanity is needed.”

Maganya noted that other countries require pastors to have a degree or certificate. “On the surface, I don’t think they are interfering with freedom of worship, unless there is a hidden motive,” said Maganya.

But Mugabo said the requirement that clergy have a bachelor’s degree will affect many young churches like the Lutheran Church in Rwanda. The Roman Catholic Church has been dominant in Rwanda, and institutions that can offer a degree in divinity for other denominations are few.

“Most of the pastors have certificates from local Bible schools,” said Mugabo. “Global missions must look at this as an emergency.”

With the new rules and regulations, Mugabo has been negotiating for affiliation with the University of Iringa, based in Tanzania. The institution is owned by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania. Mugabo has sought the use of the university’s curriculum in teaching at his church’s Bible school. The university will also award the pastors educational certificates.

“We made this plan because we can’t afford to take many pastors out of the country for study at once. We do not have enough resources, so we decided to adopt mass training from within,” said Mugabo.

(Fredrick Nzwili is a journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.)