VATICAN CITY (RNS) — Did a just-concluded meeting of Catholic bishops here open the door to rethinking Catholic teaching on homosexuality?

The question was unexpectedly left hanging in the wake of the final report of the Vatican’s synod on young people, which ended Sunday (Oct. 28). Produced in a unique collaboration between 249 bishops and some three dozen young adults, the approved summary of the proceedings nonetheless had offered a rather diluted and uninspiring welcome to LGBT Catholics.

But as happened in the previous two synods called by Pope Francis to promote a more consultative form of Catholic governance, sex – in particular homosexuality – became a flashpoint.

In fact, conservatives inside the synod hall, aided by conservative Catholic media outlets that amplified their views, waged an intense campaign to excise any mention of the acronym “LGBT” or the word “gay” from the final document. The traditionalists, who ultimately succeeded, argued that both terms would have effectively validated homosexuality and thus could undermine Catholic teaching against same-sex relationships.

Yet their victory may prove to be more semantic than substantive. The problem for the conservatives lies in the first line of the relevant section of the final document. It reads:

“There are questions related to the body, to affectivity and to sexuality that require a deeper anthropological, theological and pastoral exploration, which should be done in the most appropriate way, whether on a global or local level. Among these, those that stand out in particular are those relative to the difference and harmony between male and female identities and sexual inclinations.”

Translation: The Catholic hierarchy is acknowledging that the church needs to update its understanding of the science of sex and gender, and that also means updating the church’s theology on sexuality and its ministry to gay people.

The rest of the passage on homosexuality did seek to reassure traditionalists by reaffirming the “determinative” church view on “the difference and reciprocity between man and woman,” and the passage said it was “reductive to define a person’s identity solely on the basis of their sexual orientation.”

But that first line, inviting “a deeper anthropological, theological and pastoral exploration,” worried enough bishops that the section on sexuality passed by just two votes out of 230 cast.

“This document opens up so many minefields,” the conservative website, LifeSiteNews, quoted a synod source saying.

Afterward, the opponents’ worries only grew.

Archbishop of Philadelphia Charles Chaput at the Vatican on Sept. 16, 2014. Photo by Tony Gentile/Reuters

This section is one of the most “subtle and concerning” problems in the entire document, Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput, a member of the U.S. delegation and a leader of the conservative faction, told the National Catholic Register.

The Catholic Church “already has a clear, rich, and articulate Christian anthropology,” Chaput told the Register. “It’s unhelpful to create doubt or ambiguity around issues of human identity, purpose, and sexuality, unless one is setting the stage to change what the church believes and teaches about all three, starting with sexuality.”

Francis DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways Ministry, which advocates for LGBT Catholics, rarely agrees with churchmen like Chaput. But on this point they were in sync:

“The statement acknowledges that the church still has a lot to learn about sexuality,” DeBernardo, wrote in a blog post after the synod.

Certainly, the Catholic research on homosexuality could use an update.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, the official compendium of church doctrine developed during the 1980s, refers to homosexuality as a “psychological” condition whose “genesis remains largely unexplained.” But explanations of the origins of homosexual orientation – as well as gender dysphoria – have advanced quite a bit in the intervening years. And though the roots of sexual identity are complex, reducing them to a purely psychological cause is considered obsolete and, advocates say, dangerous.

Ignoring biological and other factors can, for example, depict sexual orientation as a matter of willpower or a form of mental illness that can be addressed by gay “conversion” or “reparative” therapies aimed at turning homosexuals into heterosexuals, advocates and health researchers say. That practice is considered so harmful – as well as ineffective and ethically wrong – that many states are banning it.

But while the leading official Catholic ministry to gay people, the Courage apostolate, has largely moved away from reparative therapy language – it promotes a chaste life as the only virtuous option for gay people – Catholic terminology on sexual identity remains confusing and often contradictory.

A 2005 Vatican document, for example, calls on bishops to bar men from the priesthood if they have “deep-seated homosexual tendencies,” a vague phrase that provides no guidance on what “deep-seated” or “tendency” means.

Cardinals, top with red caps, and bishops attend a Mass celebrated by Pope Francis for the closing of the monthlong synod of bishops, inside St. Peter’s Basilica, at the Vatican, on Oct. 28, 2018. (Claudio Peri/Pool Photo via AP)

To see how tortured the discourse has become, it’s enough to watch Catholic leaders struggle when referring to gay people at all. “Same-sex attracted” is one option, though not among gay people themselves. Many Catholic leaders still talk about homosexuality as a choice or a lifestyle and – as conservatives at this recent synod argued – they reject the very concept of a “sexual orientation” as an ideological construct that has no basis in biology or God’s plan for complementary sexes.

“There is no such thing as an ‘LGBTQ Catholic’ or a ‘transgender Catholic’ or a ‘heterosexual Catholic,’ as if our sexual appetites defined who we are,” Chaput declared in a controversial speech to the synod. “It follows that ‘LGBTQ’ and similar language should not be used in church documents, because using it suggests that these are real, autonomous groups, and the church simply doesn’t categorize people that way.”

Gay, transgender and even most straight Catholics would disagree. So would more bishops than one might suspect. Which is why the opening provided by the synod document is potentially momentous.

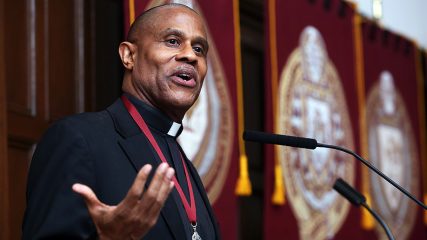

“The fact is that there are many voices on issues of sexuality present in the magisterium (official church teaching) and among the bishops themselves,” the Rev. Bryan Massingale, a theologian at Fordham University in New York, wrote in an email. “That is what this synod and those of 2014 and 2015 revealed – that the magisterium is no longer of one mind when it comes to the official teachings on human sexuality in general, and same-sex morality in particular.”

The Rev. Bryan Massingale at Fordham University. Photo by Bruce Gilbert, courtesy of Fordham University

“The great contribution of these synods is that the bishops, who previously had been chosen in large part for their ability to stifle dissent, are now being given permission – and even encouragement – to enter into the discussion and debate on human sexuality that the rest of the church has been having for the past 50 years,” said Massingale, who specializes in theological ethics.

Massingale said it is clear that the bishops know something needs to change, but he said it is equally clear that they are not sure “what that change would or should entail; that is, they are uncertain about what should be the new shape of Catholic teaching on sexuality.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean the church would change its doctrine in a radical way; it’s unlikely you’ll be seeing priests presiding over gay marriages anytime soon.

But it could help the church develop a more coherent and convincing theology for speaking about gay and transgender people, as well as more pastoral approach in ministering to them – an approach that might appeal to LGBT and young Catholics in particular rather than alienating them.

What will happen now is uncertain, as even Pope Francis admitted in his remarks to the synod on Saturday evening.

“I don’t know if this document will do something, but it should work in us,” the pontiff told the gathering. “We have studied and approved this document. Now, the Holy Spirit gives us this document to work on it in our hearts.”

(David Gibson, a former national reporter for Religion News Service, is director of Fordham University’s Center on Religion and Culture.)