Disaster psychologist Jamie Aten, right, listens to a survivor of Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas, in September 2017. Photo courtesy of Jamie Aten

(RNS) — At the turn of a new year, people often anticipate weddings, births, reunions, a promotion or other joys. Few greeted 2019 this week by counting on a flooded home or a dreaded cancer diagnosis.

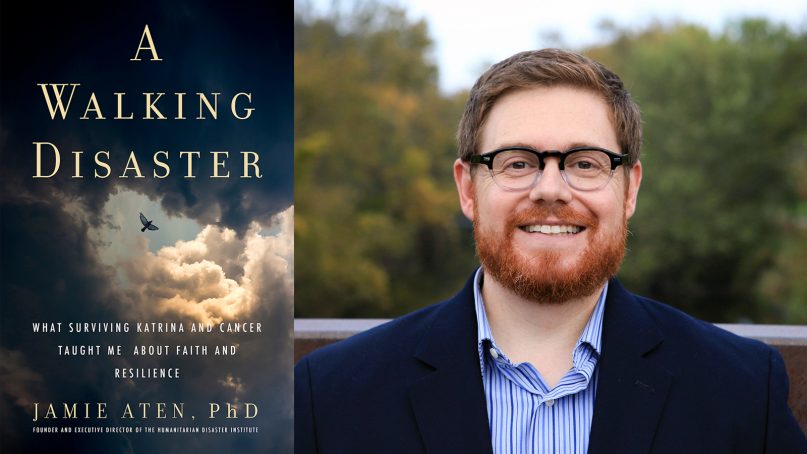

Even Jamie Aten, a disaster psychologist who founded the Humanitarian Disaster Institute at Wheaton College, wasn’t prepared for the news he received in 2013, when his doctor told him he had Stage IV colon cancer. Only 35, he had a wife and three young daughters. His academic career had just begun.

But as his oncologist told him, “You’re in for your own personal kind of disaster.”

Image courtesy of Templeton Press

Indeed, Aten would come to see his encounter with cancer through his field of study, which concerns resilience on the community level (he studied Hurricane Katrina) as well as the individual level.

Now 41, Aten has written about his journey in “A Walking Disaster: What Surviving Katrina and Cancer Taught Me About Faith and Resilience,” which will be published Jan. 14.

In it, he offers hard lessons learned from his illness, along with advice on how to lament what’s happened. He writes about how to accept help from others and cultivate a spiritual path that offers meaning and hope. As a Christian who teaches at an evangelical school in the Chicago suburbs, he tells his story through that particular faith tradition.

Aten gives a full accounting of his shortcomings, his initial denial of the gravity of the diagnosis and his wishful thinking that once the treatments and surgeries were over, everything would go back to normal.

He also writes candidly of his colostomy, the surgical procedure that followed the removal of a large chunk of his diseased colon.

The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

How is your health today?

I’m really feeling grateful. At the end of December, I had another clean scan. I now have no evidence of disease for a little over 4½ years.

Do you advise people to prepare themselves for disasters such as your illness?

It’s human nature to avoid thinking of worst-case scenarios. But the reality is that at some point in our lives, all of us will be directly or indirectly impacted by some sort of trauma. I would encourage people to think about disasters in their lives, whether it’s a mass disaster or a personal disaster like cancer.

One of the things I tried to really be conscious about was to let readers know that I didn’t always navigate this well. I do hope others will be able to take some of the lessons I learned along the way and apply it in their lives so they can live more resiliently and faithfully through the traumas and challenges they face.

You say spirituality is an important part of facing disaster. Does that mean people who aren’t believers will have a more difficult time?

An important bedrock for weathering hardship in our lives comes from being able to find meaning. That’s going to vary from person to person. One of the things the research has shown is that individuals who are able to embrace spirituality in times of hardship can add an additional layer of meaning for navigating those challenges.

Our faith can offer a way to understand the suffering we’re going through. One of the things I highlighted is the role that spiritual support can play — the way our congregation and the faith community at my college came around and supported me and my family during difficult times.

You write about the difference between optimism and hope. Explain what you mean.

I’m a pathological optimist. I’m always looking for the good in difficult situations. But we have to be careful that it doesn’t turn into blind optimism, where we’re seeing things through rose-colored glasses. Optimism played a big role in the resilience of some people I’ve seen go through disasters. But for me, I found hope was much larger and more stable. It helped me realize that if everything doesn’t turn out OK, it doesn’t mean everything has gone wrong. In my instance, it came from having hope in God that ultimately my pain and suffering would be redeemed, whether in this lifetime or the next.

Disaster psychologist and author Jamie Aten. Photo courtesy of Jamie Aten

You also write about how life doesn’t just resume the way it always has after a disaster.

One of the private practices I used to work at years ago had a sign in the clinic in the waiting room that said, ‘Normal is a setting on a washing machine.’ When we’re going through a difficulty we just want to go back to how it was. But when I was focused on wanting things go back to how it was, I realized I was missing out on living in the present. I really want to encourage those going through trauma or a challenging life experience to think about how to bring (the part of your) past that’s helpful to you, but to focus more on moving forward.

In your book, you describe how you were finally able to talk about your colostomy. Do you feel like it’s more acceptable to do so?

I definitely think society has come a long way in accepting individuals who have had colostomies. At the same time, I still think there’s a lot of stigma. It’s still the punchline of jokes.

For me, it was initially a symbol that cancer had won. I attached a lot of meaning to it. Even as I talk to you now, it’s still a struggle. It was easier to write about it than openly talk about it.

There a national, and maybe even international, organization for people who have colostomies that provides support and education around it. My wife and I had gone to a support group meeting through that organization. But it was still a challenge for me. It was one of the first times I was outwardly letting people know that I had the surgery. There was a therapist there who provided education. I ended up doing therapy with that person for a period of time and it really helped me to start to come to terms with how my body had changed. It’s still a challenge for me.

Why is it important to be upfront about it?

I tried to write the book without sharing that part of my journey. What I realized was that it was a huge part of my cancer journey. I realized that that surgery helped save my life. It’s been a tug of war coming to terms with it — at times I’m upset about it; at times grateful for the procedure. I realized if I didn’t share that part of my story I wasn’t being authentic with the reader. It was a big part of my experience.

Initially I let scars create walls in my life. Now I see the scars as doors to let others into knowing me more authentically I realized it’s our scars that allow us to connect to other people in more deep ways and perhaps even be recognized.