(RNS) – Nushmia Khan has been to a lot of weddings.

A former visual journalist and wedding photographer, she has watched dozens of Muslim brides and grooms sign marriage contracts at their nikahs, or Islamic marriage ceremonies. The agreement, known in Urdu as a nikah nama and in Arabic as aqd zawaj or katb-al-kitab, is typically a plain paper document covered with legalese. Couples often signed off without much care.

Most of the agreements looked as though they had been composed on Microsoft Word. But she noticed that a few brides had commissioned artists and calligraphers to create expensive, customized contracts for their ceremony – so elegant, Khan said, that you would want to frame it in your entryway at home. When it came time for her own nikah in 2013, she wasn’t satisfied by the basic template so many of her friends had used.

Nushmia Khan. Courtesy photo

Khan, now a 29-year-old mother living in Allentown, Pa., spent hours going to craft stores, decorating the document with colorful embellishments, fancy paper and an elegant envelope. But she was a busy bride with limited time, and things didn’t quite go the way she hoped.

“It was so frustrating,” she recalled. “I was spending so much time finding all these beautiful texts to include in my nikah nama but it just looked like the ugliest thing in the world. It’s hidden away somewhere now. I would be so embarrassed now to dig it up and show it to you.”

Khan didn’t want other couples to have the same experience. So last month, she launched a business called Nikahnama to make high-quality, decorative Islamic marriage contracts accessible to Muslim couples across the globe.

“It made me so sad that my own nikah contract wasn’t beautiful and that such options weren’t easily available,” she said. “There’s clearly a need for beautifully designed nikah namas, but there’s a void in the market.”

Working with Pakistani miniature artist and calligrapher Muhammad Farooq Ishaq, Khan created three hand-painted designs that are custom printed with the couple’s name and wedding date.

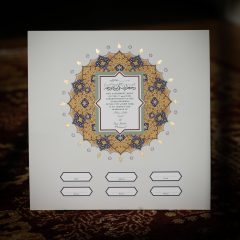

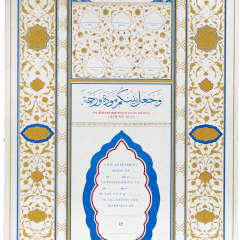

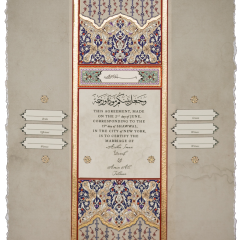

One design is modeled after the nikah nama of Princess Ziya-i-Sultaneh, an Iranian royal in the Qajar dynasty from the 1800s; another is based on the design of an antique Malaysian illuminated manuscript; the third is inspired by a Mughal folio.

“I wanted to create a project that makes being Muslim a more beautiful experience,” she said.

- An example of Nikahnama’s rosette design. Photo courtesy of Nushmia Khan

- An example of Nikahnama’s ziya design. Photo courtesy of Nushmia Khan

- An example of Nikahnama’s Nusantari design. Photo courtesy of Nushmia Khan

To be sure, an eye-catching contract is hardly necessary for an Islamic marriage. In fact, Muslims are not even required to have a written contract.

The contract’s chief purpose is to make the couple’s union Islamically legal through a public declaration.

“By the mere act of entering into a nikah … the heavens smile, and what was once forbidden becomes rewarded,” Khan said. “Muslims believe that God himself lifts a divine prohibition on intimacy between two unmarried individuals.”

The nikah makes the public stand as “witnesses that the marriage is legal and all its natural consequences are legitimate,” explained Imam Abdullah Dibba, who leads Philadelphia’s Bait-ul-Aafiyat Mosque. “Likewise, through the announcement, in case of any dispute that may involve children or lead to separation, every right of the woman would be protected.”

A nikah contract is also an opportunity for the couple to negotiate their relationship and their rights — particularly protecting the bride’s financial security by establishing her groom’s responsibilities to her.

Chief among those responsibilities is financial support in the event of a divorce or widowing. A bride can request a regular allowance, for example, or claim her right to work or continue her education. The couple can also negotiate their physical relationship or other details.

“It makes you feel comfortable and protected,” Khan said. Her own nikah contract included stipulations that she would not have to work if she did not want to and to limit her husband’s ability to take a second wife.

But many couples forgo these protections and rush through the nikah.

Many Muslim women in Pakistan, where Khan’s family hails from, sign their nikah contracts without reading them and accidentally sign away their rights.

Her own cousins and aunts in Pakistan say they not only were unable to read their contracts, but their local imam had stricken through language in the contract that would allow them the right to file for divorce without returning their haq maher – the mandatory payment a husband must give his wife, the amount of which is negotiated in the nikah contract.

That’s a common story among Pakistani women.

Miniaturist Muhammad Farooq Ishaq works on a calligraphy design in Lahore, Pakistan. Photo by Nushmia Khan

“I want Muslim couples to really, really think about what they put in their nikah contracts, not just who they’re going to invite to their wedding or what they’re going to wear,” Khan said. “When you’re intentional about your contract, your marriage will have a more solid foundation so you don’t have to fight through this stuff.”

That’s part of the reason why Khan is so vested in Muslim couples’ proactively thinking about their marriage contracts. A better, more thoughtful nikah contract can act like a prenup that means a stronger, healthier marriage, Khan says. Such a “holy sacrament” deserves to be honored as the most important part of an Islamic wedding, not hidden behind the scenes, she said.

And if it takes attracting people with pretty calligraphy to make them realize the importance of the nikah contract, then so be it.

Client Rashid Hussain, who got married in March 2018, told Religion News Service that incorporating a decorated contract into his wedding was an opportunity to resurrect a lost Muslim craft.

“I value tradition and saw ordering the nikah nama as a way to honor both our religious heritage and culture,” Hussain said. He and his wife now keep Khan’s custom design on display in their home.

Under Iran’s Safavid and Qajar dynasties, particularly in the 19th century, marriage documentation emerged as a unique art form. Elite Persian Muslims led the way in producing gilded marriage contracts richly decorated with elaborate illuminations and calligraphy in vibrant pigments of lapis lazuli, cinnibar and gold. They served not only as wedding souvenirs, but also as a way to document the wedding – the couple’s introductions, the haq maher payment and the wedding’s required witnesses – while lavishing the newlyweds with extensive prayers and blessings.

Nikahnama marriage contracts await the right couple. Photo courtesy of Nushmia Khan

In researching these Persian marriage contracts, Khan learned that the marriage contracts of many Persian Jews were influenced by the Islamic art of their neighbors. The tradition of artistic Jewish marriage contracts, or ketubahs, was largely rooted in Sephardic Jews but became popular among American Jews in the 20th century.

Today, many Jewish couples around the world sign a lavishly decorated ketubah in their wedding ceremony and display the document in their homes. For some Jews, if the ketubah is lost or damaged, the couple cannot live together until it is replaced.

In one recent interfaith wedding, a ketubah performed double duty as a nikah contract for a Jewish-Muslim couple. Sellers on Etsy offer ketubahs in Arabic and Hebrew for interfaith weddings, and in 2011, The New York Times reported on a growing movement of Christian couples using ketubahs in their weddings.

“We wanted a permanent reminder of the covenant we made with God,” one woman told the Times. “And this piece of paper, this beautiful piece of art, is the sign of our covenant.”

Unable to find options in their own community, some Muslim couples have turned to ketubah designers to produce their own keepsake nikah contracts, Khan said. Others have found alternative routes. A Muslim attorney created the website NikkahBuilder.com to help couples draft customized nikkah agreements based on various free templates, and his service offers keepsake versions of the contract. A Canadian designer worked with his imam and his sister, a calligrapher, to design a now-viral marriage certificate for her wedding.

Now, Khan is fielding requests from married Muslims who say they wish they had been able to have a keepsake marriage contract. So she’s created an option for anniversary contracts – “like a vow renewal,” she explained. She hopes to soon offer illustrated birth certificates and handmade, artisan prayer rugs.

“For people to feel strong in their faith, they need to feel like their religious practices are beautiful,” she said.