(RNS) — The history of the moral aphorism “speak no ill of the dead” (important enough, apparently, to have its own Wikipedia page) goes back at least to the fourth century. In today’s morally fragmented culture, it is one of the few claims to garner wide support right across the political spectrum. Democrats and Republicans were united last week in condemning President Trump’s speech to workers at a tank factory in which he went after John McCain just months after the Arizona senator’s death.

These sentiments are understandable, of course, if one believes that McCain is still alive in some sense. This is presumably what is meant when some of Trump’s critics begged him to let McCain “rest in peace.”

What’s harder to understand is the criticism from those on the secular left; if McCain is simply gone, and thus cannot rest at all — in peace or otherwise — Trump’s words cannot wrong McCain because McCain no longer exists.

Instead, it seems as if what both sides might agree on is that what offends us is the attack on McCain’s dignity — or even the dignity of his death.

The problem with invoking dignity, however, is that in our pluralistic culture, not all of Trump’s critics agree on what the dignity is. Indeed, when it comes to our cultural debate over euthanasia and assisted suicide, the opposing sides very often employ the concept of dignity in support of very different positions.

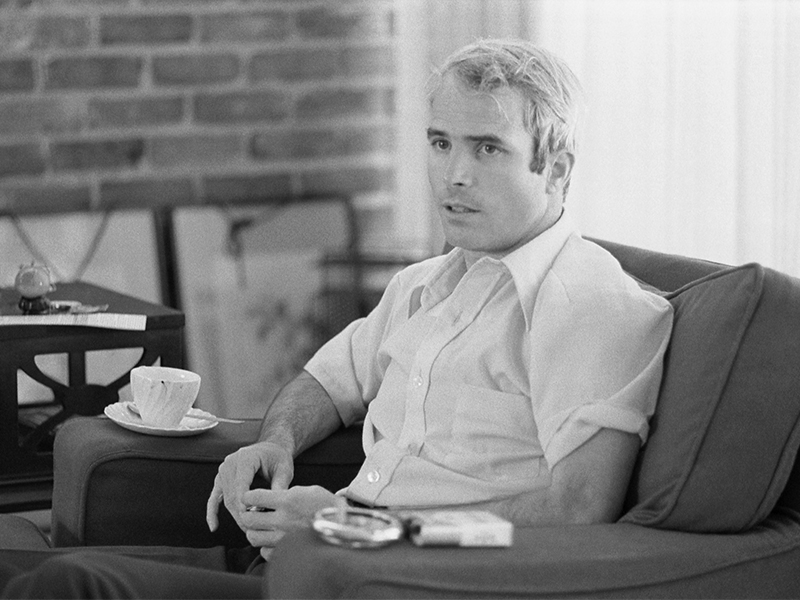

John McCain on April 24, 1973, shortly after his release from a Vietnamese POW camp. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran/LOC/Creative Commons

Those who oppose ending human life for medical reasons tend to invoke the dignity of the human person, which is violated in a radical way when someone aims at their death. Those who support these practices, on the other hand, very often claim that they want people to “die with dignity.”

Indeed, many U.S. states that have legalized these practices in recent years put the term “dignity” in the name of the legislation — like Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act.

Some prominent thinkers have even rejected altogether the concept of the intrinsic dignity of human life as a moral imperative. In a much debated 2003 article by the bioethicist Ruth Macklin titled “Dignity is a useless concept,” she argues that dignity is embodied in personal autonomy — the person’s wishes about their death. Elsewhere, Macklin has refused to acknowledge that desecration of a dead body actually harms the dignity of the body or of the person to whom it belongs. She reduces the wrong of such desecration to how it impacts other living people.

(This is akin to saying, as some have, that Trump has wronged McCain’s memory. Certainly Trump may have wronged the people who knew John McCain, his family and friends who are still with us. However, I don’t think it is what most people have in mind when they so heartily criticize Trump’s words about McCain.)

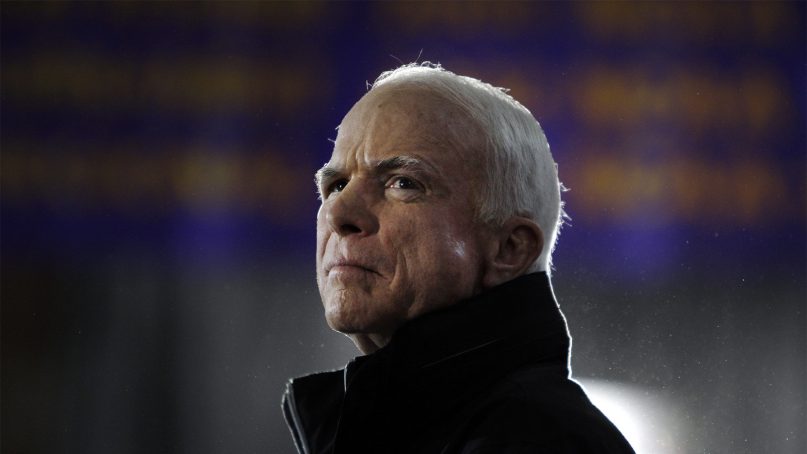

President Trump speaks in St. Charles, Mo., on Nov. 29, 2017. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

What secular thinkers are really getting at here comes clear in a 2008 article in The New Republic by Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker titled “The Stupidity of Dignity.” Pinker alleged that dignity is merely a stealthy way of importing “fervent religious impulses” into issues where they don’t belong.

And he is something close to right about this. There simply is no way to ground a certain concept of dignity without recourse to a “thick,” or very specific, articulation of the good — one that is close to a religious concept of what gives humans worth.

As our secular culture distances itself more and more from its theological roots, these kinds of concepts become increasingly difficult to ground. Once a culture severs its ties from those roots, it can hold on to key moral concepts for a couple of generations, even after losing touch with the reasons for believing in them.

But eventually the culture will push for moral coherence and root out views that can no longer be defended. We have seen this play out in our own time in the U.S. when it comes to the sanctity of human life.

In the absence of theological grounds for believing that McCain’s dignity is still at stake, Trump is simply doing what he’s been accused of doing since he took office: riding roughshod over norms, testing the basis for our pieties. Trump’s secular critics need to pause and think about what grounds their outrage. They may find that it is actually quite difficult to defend without something very much like theological premises.

(Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics and a board member of Democrats for Life. His forthcoming book “Resisting Throwaway Culture” will be released on May 15. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)