(RNS) — When confronted with the views of a candidate from “the other” party, have you ever felt so upset that you had to change the channel in anger or disgust? Have you ever become profoundly anxious at the prospect of having to engage with your family about politics?

Have you ever transferred out of a course because you couldn’t handle the ideology of the instructor? Have you left a church community because you disagreed with the views of the pastor or your fellow worshippers?

Many have. Many of us refuse to have our perceived enemies, even thoughtful ones, challenge our safe, comfortable views. We prefer not to engage.

We might be tempted simply to dismiss this state of affairs as what any pluralistic Western republic has to put up with. After all, if a culture genuinely tries to welcome multiple and even antagonistic understandings of the good, could there really be another outcome?

Maybe. Three years ago, in the heart of the 2016 presidential election cycle, Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles said, “It is clear that we need a new politics — a politics of the heart that emphasizes mercy, love and solidarity.”

This kind of politics is especially important, perhaps, to Christians caught up in the country’s polarization and incoherency. These plagues don’t just shove today’s complex issues into a simplistic right/left framework; they prompt us to view our ancient theological traditions through the lens of the culture wars.

Christian liberals and Christian conservatives as a result often hold views indistinguishable from those of secular liberals and conservatives, putting Christianity at the service of America’s political tribes.

There are a few reasons for hope.

As Eugene Robinson recently stated, “My view is that the traditional left-to-right, progressive-to-conservative, Democratic-to-Republican political axis that we’re all so familiar with is no longer a valid schematic of American political opinion. And I believe neither party has the foggiest idea what the new diagram looks like.”

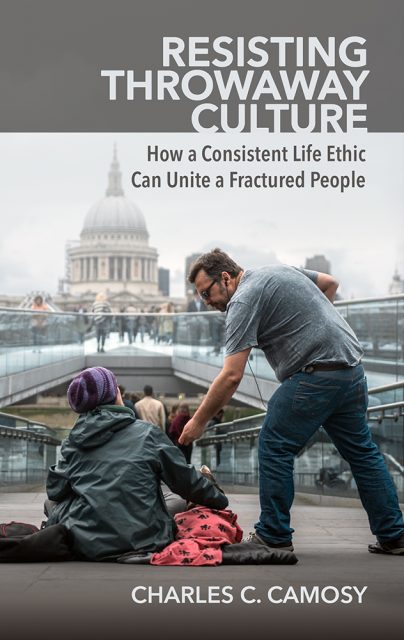

“Resisting Throwaway Culture” by Charles A. Camosy. Image courtesy of New City Press

The old coalitions do seem to be falling apart. Donald Trump, who won without being clearly liberal or conservative, has remade the Republican Party (if it still exists at all) into a very different thing.

At the same time, many evangelical Christians, whose “moral majority” generated the last iteration of the Republican Party in the late 1970s, are increasingly uncomfortable with today’s GOP.

Southern Baptists have also begun to distance themselves from the Republican Party, as evidenced by the protests surrounding Mike Pence’s speech last year to the Southern Baptist Convention.

Working class Catholics — once the Democratic base — have been pushed out by a hyper-secular party driven by sectarian identity politics. Large numbers of Latinos and Latinas, despite the Democratic party’s “all-in” stance and purity tests on abortion, strongly identify with the goals of anti-abortion pro-lifers.

Many pundits see the trend reflected in the 2018 midterm elections, arguing that the voting reflected not a so-called “blue wave” but, rather, the uncertainty and turbulence of a country undergoing a profound political realignment.

If the ranks that took shape in the 1970s and 1980s culture wars are finally breaking apart, it may be younger people who finally make them scatter. Half of all millennials refuse to identify as Democrat or Republican, and 71 percent see a need for a major third party. They are fiercely committed to social change and don’t see government as a primary way of effecting it.

There is no script for replacing a political culture. Some worry that radical moral diversity will leave us so fragmented that we will never find a way to write such a script together.

Indeed, if we plow ahead too quickly — if we settle for politically motivated “10-point plans” or “contracts with America” — we will miss a rare opportunity to do something lasting and significant.

In speaking recently to anti-abortion groups, I’ve suggested that maybe the most important thing we can do right now is to take a deep, cleansing political shower. Scrub away grime that has built up over years or even decades. Step away from the anxieties of the news and election cycles and focus instead on fundamental questions.

What do we value most in life? What grounds those values? How do those values suggest a way of living together with our neighbors?

A revitalized Consistent Life Ethic — especially as understood and articulated in the Roman Catholic tradition by Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and (especially) Pope Francis — could provide a path to unifying a fractured culture around a vision of the good.

Pope Francis arrives for his weekly general audience in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican, Wednesday, April 24, 2019. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Through the church’s CLE, rightly understood, a new generation can not only challenge our impoverished and incoherent political imagination but also can begin the hard work of laying out the foundational goods and principles upon which whatever comes next can be built.

To many, the CLE is equated simply with a pro-life or anti-abortion stance. But in the encyclical “Caritas in veritate,” Benedict said that it is false to distinguish between “pro-life” issues (where the church is thought to have more conservative views) and “social justice” issues (where the church is thought to have more liberal views).

Abortion, euthanasia and embryo-destructive research are to be understood as social justice issues — just as global consumerism, ecological concern and care for the poor are to be understood as life issues.

What the CLE really opposes is what Pope Francis calls “throwaway culture” — a mentality in which everything has a price, everything can be bought, everything is negotiable. This way of thinking has room only for a select few, while it discards all those who are unproductive.

Such a culture reduces everything — including people — into mere things, whose worth consists in being bought, sold, or used, and which are then discarded when their market value has been exhausted. Francis insists that the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” applies clearly to our culture’s “economy of exclusion.” In the pope’s view, “Such an economy kills.”

In a throwaway culture, a primary value is maintaining a consumerist lifestyle. To cease caring about who is being discarded, most of us must find a way to no longer acknowledge their inherent dignity. Instead of language that affirms and highlights the value of every human being, throwaway culture requires language that deadens our capacity for moral concern toward those who most need it.

The values of the CLE, in other words, are the irreducible dignity of the person, nonviolence, hospitality, encounter, mercy, conservation of the ecological world and giving priority to the most vulnerable.

These are not necessarily Catholic values alone but are written on the hearts of many kinds of people. Speaking at a Georgetown conference on political polarization, David Brooks, a non-Catholic thinker, suggested that a Catholic social vision is “all we have” to resist the forces that are tearing us apart.

Significantly for this project, millennials of many different religious and political stripes view Pope Francis in positive light. His pontificate has demonstrated that the Catholic tradition’s insights and values are attractive outside the church. And because CLE principles come from the Gospel of Jesus Christ as revealed in scripture and other parts of the Christian tradition, biblically focused evangelicals will find much that resonates with them.

Furthermore, because CLE often addresses its arguments to “all people of good will,” those who have faith in something other than Christianity (including those who have no explicitly religious faith) will find much to engage as well.

The seeds of morality necessary to generate a new politics can take root only if we focus first on living out the CLE in our daily life choices, if we take seriously Francis’ insistence on a culture of encounter, whereby we meet the vulnerable and marginalized personally by disrupting our routines and going to the peripheries of our familiar communities.

In the larger scheme of things this may seem small, especially for those who focus on big policy debates. But small seeds produce saplings, then trees, then forests — in this case, the trees and forests necessary to support a new and healthy political ecosystem.

(Adapted with permission from “Resisting Throwaway Culture” by Charles A. Camosy, published by New City Press. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)