(RNS) — When Waleed Ahmad feels his stomach clench with hunger during Ramadan, he thinks of the pangs that impoverished people — who don’t have a filling iftar meal to look forward to — must feel.

“The purpose of fasting is to connect with your creator spiritually,” said Ahmad, the director of programs at Humanity First USA, a Muslim-led aid organization. “But it’s also to realize there are people in the world who don’t get those two meals a day. So let’s at least give our lunch money to them.”

Now in its third year, Humanity First USA’s Fasting to Feed campaign aimed to collect $100,000 during Ramadan’s final 10 days to support its network of food pantries and soup kitchens across the country.

The organization’s push is part of a wider point that many Muslim charities and NGOs are trying to make during the holy month.

“As Muslims we know that blessings and reward and forgiveness from God can be multiplied in this month,” Ahmad explained, citing a saying of the Prophet Muhammad that describes Ramadan as a time when Satan is chained in hell and the gates of heaven are thrown open. “That’s why they contribute more in Ramadan.”

It’s also why mosque leaders take a pause during Ramadan taraweeh prayers to make fundraising pitches for renovations, expansions and upkeep on their houses of worship. And it’s the reason Muslims around the country find their inboxes and WhatsApp groups are filled with more requests for donations than ever before.

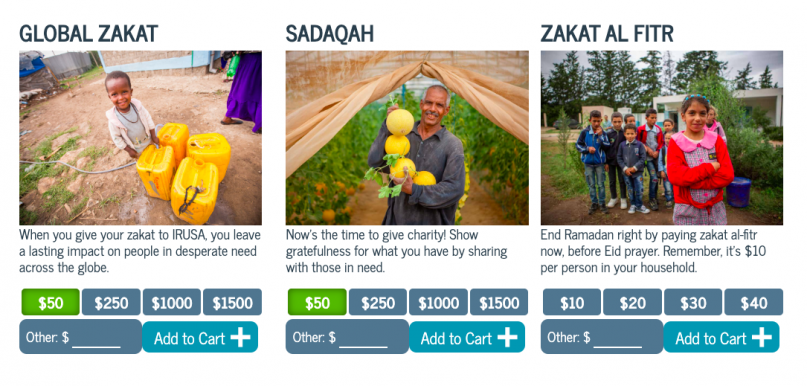

Muslim charitable organizations put particular emphasis in Ramadan on the various obligations Muslims have to support the less fortunate: zakat, an obligatory wealth tax; sadaqah, acts of voluntary charity; fidya, a donation by those who are unable to fast; and fitrana, a small donation that must be given by the end of Ramadan so that needy Muslims can celebrate the festival of Eid al-Fitr with the rest of the community.

Some have crafted special programs to capitalize on Ramadan. The popular Muslim crowdfunding site Launchgood allows users to automate their giving for each day of the month during its annual 30 Days of Giving challenge. The website MyTenNights, launched two years ago, automates donations during the last 10 days of Ramadan so that Muslims don’t miss out on the opportunity to give on Laylat al-Qadr, considered the most blessed night of the year. NGOs, from humanitarian organizations like the Islamic Relief USA to civil rights advocacy groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations, put zakat calculators on their websites to help Muslims fulfill their religious obligations.

Research on U.S. Muslim philanthropy remains thin, however.

Rafia Khader. Courtesy Lake Institute on Faith & Giving

“There’s still a lot about Muslim giving that we don’t know,” said Rafia Khader, who helps lead the Muslim Philanthropy Initiative at Indiana University’s Lily Family School of Philanthropy. Until recently, she said, few who study philanthropy were interested in Muslim giving, and Muslim institutions didn’t have the bandwidth to do so.

That is changing, according to Khader, as Muslims themselves begin “writing (their) own narrative.” Projects like the Indianapolis non-profit Center on Muslim Philanthropy, founded in 2014, aim to research and advance the field of Muslim giving. (Last month, its founder, Shariq Siddiqui, was also named director of the Muslim Philanthropy Initiative.)

There’s also the Pillars Fund, a donor-advised fund founded in 2010 to focus on funding American-Muslim projects and storytellers, and the American Muslim Fund, begun in 2016, which largely funds mainstream charitable organizations.

“I think American Muslims have a responsibility to showcase what it means to be Muslim,” said Muhi Khwaja, co-founder of the American Muslim Fund. “We can’t expect other people to do that for us. We have to be proactive and show how we’re giving back through philanthropy. It’s our civic duty to represent Islam.”

Muhi Khwaja. Courtesy American Muslim Fund

AMF has distributed more than $1 million to food banks, hospitals, shelters, museums and mosques across the country. When organizations receive funding through AMF’s funds, as the Houston Food Bank did after Hurricane Harvey, they receive a check that identifies the donor as an American-Muslim family.

“I wanted to create something that would have a longer-lasting impact in the Muslim community,” Khwaja said. “The value we provide is being able to showcase Muslim philanthropy, Muslim generosity and the collective impact we have.”

But Islam’s place in U.S. culture — not to mention its unique theological understanding of charity — also makes it harder to quantify Muslim philanthropy.

Since 9/11, surveillance of large Muslim-run charities for possible terrorist ties has left many U.S. Muslims scared to donate for fear of being prosecuted for unknowingly providing material support for terrorism. In response, Muslim leaders requested federal guidance on which charities Muslims may safely give to but received no answers.

Instead, research has shown, Muslims have donated in cash and begun shifting their donations toward domestic civil rights organizations.

Further complicating the attempt to quantify the community’s giving is the feeling among many Muslims that they should not report their giving publicly, Khader said. Anonymous giving is also typically considered more righteous in Islam, so as not to tempt the donor to show off or humiliate the recipient of the charity. A famous saying of the Prophet Muhammad encourages giving charity so quietly that one’s left hand does not know what the right hand has spent. But some verses in the Quran also recommend public donations, to help set an example for others in society.

For Muslims, philanthropy is baked into the system with religious obligations like zakat and is not simply about a donor’s individual goodwill, Khader explained.

“A lot more Muslims are trying to not just feed poor people abroad, but the poor people that are living in their own community and even just hosting local Muslims for iftar,” she said. “That also is a kind of giving, although it’s considered informal philanthropy and nobody really studies it. According to the definition we have, any action done for the sake of God and for the public good is considered philanthropy within Islam.”

For Muslims whose families immigrated recently to the U.S., it’s common to send their zakat and sadaqah abroad, back to the communities they grew up in or to Muslim-led NGOs addressing humanitarian causes. Such projects include the Karam Foundation, which has raised more than $100,000 during Ramadan to distribute food kits and warm meals to families in Northern Syria, and Penny Appeal’s campaigns for water wells, orphanages and more, from Gambia to Pakistan.

But early Islamic scholars as well as contemporary leaders have emphasized the importance of distributing zakat locally to fulfill one’s obligations to one’s own community. Organizations like the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding have recommended that Muslims exercise serious caution when sending their zakat abroad to reduce the risks of running into counter-terrorism financing laws.

Now, as Muslim institutions develop a stronger foothold in the U.S., Khader said, Muslims are increasingly using their zakat to fund domestic projects, from local Muslim women’s shelters to projects training Muslim political leaders. A small informal survey conducted by Zakatify, an app launched last year by serial entrepreneur Shahed Amanullah to make giving zakat easier, found that about the same number of American-Muslim respondents now give as much locally as internationally.

A fundraising email from the Muslim Public Affairs Council on May 31, 2019 showed potential donors that the organization was zakat-eligible.

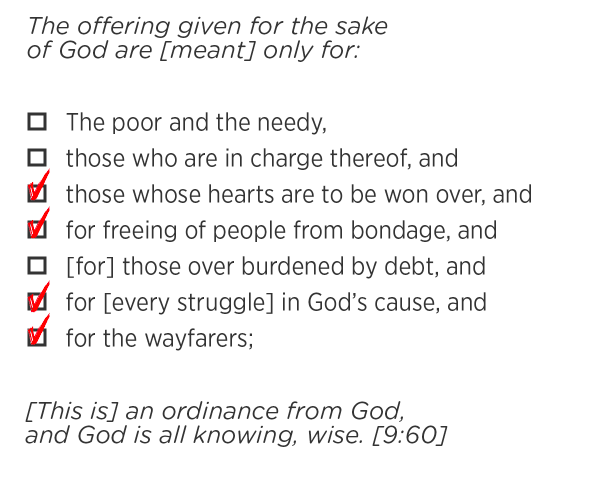

They are also seeing a wider range of activities as eligible for zakat. In the U.S., Islamic scholars have also increasingly interpreted the Quranic guidelines on zakat to include funding mosques, Islamic schools and even non-profits advocating for Muslim civil rights.

The Quran’s instructions to give zakat to the enslaved, for instance, is interpreted by some scholars and activists, including those at Believers Bail Out and the Tayba Foundation, as a modern call to action to help incarcerated Muslims. Organizations that research Islam and Muslims, such as the Yaqeen Institute in Texas, also say that they fit into the category of zakat beneficiaries that “win over hearts.”

“In the past, a lot of Muslims would have said, ‘Well, I don’t know that you’re zakat-eligible,’ Khader said. “But as these organizations and scholars are making these arguments, more Muslims are feeling comfortable giving zakat in all these other ways.”