(The Conversation) — Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first-ever democratically elected president, died unexpectedly during a trial in June 2019. He was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, an almost century-old Islamist group that rose to power after the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.

Its political tenure was short. Morsi was deposed by a coup in 2013, on the one-year anniversary of his election. Egypt’s new military regime declared the Muslim Brotherhood, whose political coalition received 38% of the votes in the 2011 parliamentary elections, a terrorist organization. Its members have been arrested, jailed and tortured. Morsi was sentenced to death, though the sentence was overturned on appeal.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s fall recalls the sudden decline of another once-powerful Islamic group: Turkey’s Gulen movement.

In July, Turkish president Tayyip Erdogan marked the third anniversary of a failed coup accusing Fethullah Gulen – a former ally and leader of an influential Islamic movement – of masterminding the attempted overthrow of his government.

Gulen, a Turkish scholar and cleric who has lived in the United States for 20 years, has consistently denied involvement in the coup. He founded an Islamic community in the 1970s. By 2013, his movement had millions of supporters worldwide, as well as media institutions and schools in over 100 countries, including some 150 charter schools in the United States.

The New York Times once presented the movement as promoting “a gentler vision of Islam.” In 2014, the BBC called Gulen “Turkey’s second most powerful man,” after then Prime Minister Erdogan.

Now, Erdogan has declared the Gulenists to be terrorists. Those who are affiliated with the movement have been systematically purged and jailed.

How did the Muslim Brothers and the Gulenists fall so far, so fast?

The authoritarian state

My research on Islam and authoritarianism indicates that both groups were victims of the same dangerous combination: an authoritarian state, Utopian ideas about Islam and unreliable friends.

Both in Egypt and Turkey, Islamic movements have struggled to survive in authoritarian regimes that exert strong control over religious practice.

Egypt’s autocratic presidents keep mosques and Al-Azhar, a leading educational institute of Sunni Islam, under their thumb.

In Turkey, a government agency called the Diyanet oversees religious affairs and defines for the Turkish people what “correct Islam” is. Under the strongman regime Erdogan has built since 2013, which combines religious conservatism, nationalism and authoritarianism, the Dinayet has been a crucial instrument of social control.

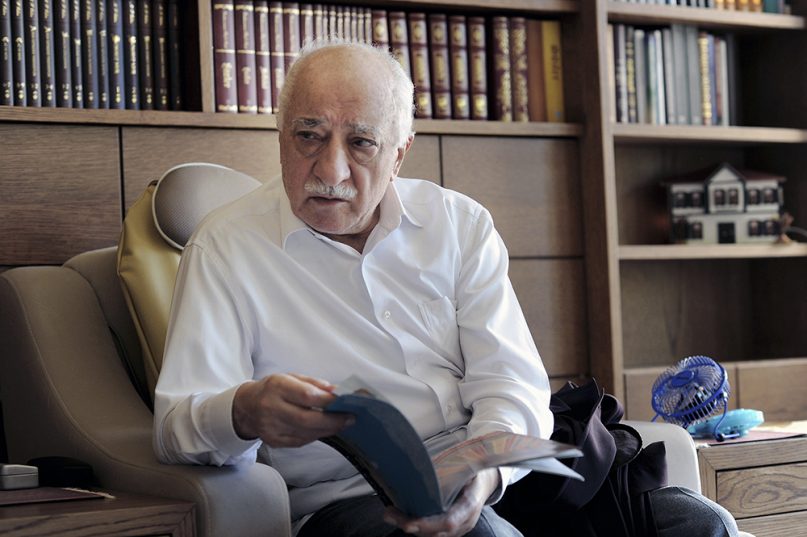

Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen at his residence in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, in September 2013. Gulen has lived in exile in the U.S. for two decades. Photo by Selahattin Sevi/Zaman Daily via Cihan News Agency

Given these political conditions, both the Muslim Brothers and the Gulenists have since their founding had a well-founded fear of persecution. Their leaders, several of whom I interviewed in 2013 during my book research, assumed that these groups could not survive unless they became powerful enough to control state institutions entirely.

That fear has proven to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Their efforts to capture the state institutions were initially so successful that they created a backlash. Political elites in Turkey and Egypt turned against these powerful groups, designating them enemies of the state.

Utopian Islam

The comparison I’m developing here will be unacceptable for most Gulenists.

Gulen’s followers see themselves as nonpolitical, a civil society organization – sharply different from the Muslim Brothers, an Islamist political organization with an explicitly political agenda.

And it is true that the Gulenists never established a political party. But their initial alliance with Erdogan – and, later, their conflict with him – demonstrates that Gulenists are a deeply political force in Turkey.

Like the Muslim Brothers, the Gulenists have a certain Utopian vision of their religion. Both groups see Islam – albeit different versions of it – as the solution to all society’s ills.

Religion is, for these organizations, a blueprint that should guide Muslims in every detail of their life, from restroom manners to governance. The judiciary, military and police, too, should be “Islamic.”

In their quest to control everyday life in Turkey and Egypt, the Gulenists and the Muslim Brothers made enemies. They alienated secular citizens, who rejected the “Islamization” of their country. They also angered other Islamic groups, who felt themselves being edged out of power.

Wrong partners

Even one-time allies have turned against these groups.

This is a sign of the third feature that, I found, contributed to the downfall of the Gulenists and the Muslim Brotherhood: Neither is very good at choosing their friends.

Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, former head of the Egyptian armed forces. Photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo/Creative Commons

Within a month of winning the Egyptian presidency, Morsi promoted to defense minister and head of the armed forces General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a young general. Morsi thought al-Sisi had strong enough Islamist leanings that he would be friendlier to the Muslim Brotherhood than other high-ranking officials in the Egyptian military.

A year later, al-Sisi staged the coup that overthrew Morsi. Once in power, he designated the Muslim Brothers a terrorist organization.

The Muslim Brothers have made this mistake before. In the 1950s, they believed Gamal Abdel Nasser – the military mastermind of Egypt’s 1952 revolution – was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. But after using the group to seize power, President Nasser persecuted his former partners.

The Gulenists have made similarly disastrous partnerships.

Between 2006 and 2011, they allied with Erdogan, helping him eliminate Turkey’s secular political establishment. But once Erdogan consolidated his personal power, he turned against all his former allies – the Gulenists included.

Concerned about Erdogan’s persecution of their movement, some Gulenists came to see General Hulusi Akar, then the head of Turkey’s armed forces, as the man to check the Turkish president’s dictatorial tendencies. Arguably, they expected some sort of military intervention against Erdogan.

Whether Akar actually played a role in the 2016 coup attempt is still a mystery in Turkey. He insists he had nothing to do with the effort to overthrow Erdogan.

In 2018, Erdogan promoted Akar to defense minister. With Akar’s support, more than 16,000 military officers have been fired for allegedly being Gulenists.

Lessons to be learned

Just a few years ago, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Gulenists were powerful enough to imagine that their Utopian goal of remaking society in their image was within reach.

Today their leaders are exiled, dead and jailed. Their properties have been seized, their reputations tarnished.

The downfall of these two Islamic organizations is a cautionary tale for other religious groups with political ambitions in the Muslim world.

Trying to run a country based on a single Utopian vision of what an ideal Islamic society looks like is risky business. Add authoritarianism to the mix, and the chances of failure grow. Choose the wrong allies, and the result can be deadly.

(Ahmet T. Kuru is a professor of political science at San Diego State University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)