(RNS) — October is upon us, and with it the beginning of the pre-Halloween media season — for magic, the occult, witchcraft and, not least, the final season premiere of “American Horror Story,” TV’s homage to the slasher films of the 1980s.

But the truth is we have been in an extended season for witches since at least the election of Donald Trump. The “witch aesthetic,” which features transgressive makeup and Goth-inflected fashion, is a counterculture look that says #resistance.

But the witch trend also says something more profound about the current generation’s ideas about glamour and our dependence on technology to fashion selves we can identify with and love.

RELATED: Is Tumblr witchcraft feminism – or cultural appropriation?

If feminist empowerment doesn’t sound exactly glamorous, you haven’t been watching Disney lately. Sexy female villainy is in. M.A.C. Cosmetics has a line of “Venomous Villains” inspired by dark Disney characters like Maleficent. Makeup brands like Urban Decay regularly give their products titillating names like Vice and Tryst.

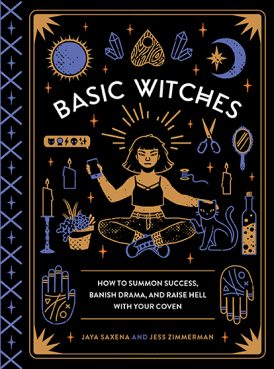

Courtesy of Quirk Books

More pertinently, the word “glamour” itself is a witchy one, as Jess Zimmerman and Jaya Saxena explain in their 2017 how-to guide, “Basic Witches: How to Summon Success, Banish Drama, and Raise Hell with Your Coven”: “It’s no coincidence that glamour — the term for an appearance-changing charm in early English tales of witches and fairies — has become a modern word denoting charisma, beauty, and élan.”

Glamour, they continue, is a reclamation of a magical force. “Beauty is something that women alone are expected to perform, involving mysterious rituals, talismans, and bottled potions.” These days, technology is enlisted alongside these traditional aids. Never mind that women’s affection for cosmetics is often held up for ridicule, not respected as dangerous. “The beauty arts are scoffed at precisely because they make women powerful,” the authors write.

In a curious turn, however, glamour is ultimately not about artifice, but authenticity. “In reality, you’re not deceiving people when you indulge in cosmetic shape-shifting,” Zimmerman and Saxena conclude. “Rather, you’re letting your true self shine through.” Shape-shifting is only the art of making your external self resemble a vision — your vision — of who you want to be.

Of course, every act of self-creation doubles as an act of subversion. In a culture that demands women look “pretty,” it allows women to reclaim sexual and personal power. So while glamour is the goal, Saxena and Zimmerman recommend that would-be witches place a “hex” on standard expectations of femininity by shaving their heads.

“We witches cackle in the face of perfect femininity,” Saxena and Zimmerman write. “We aren’t interested in conforming to standards so much as triumphantly watching people squirm when the standards are destroyed. Your witchy hairdo can be an engine for confidence and power— power that comes from you alone.”

Photo by M Jurcevic/Creative Commons

Besides the subversion of society’s beauty standards, the witch aesthetic is a statement of another profoundly millennial value: a scorn for the unadorned body as fundamentally devoid of meaning. Only once artifice — magic — is applied do our bodies have legible meaning.

In this way, modern witch culture inherits much from the anti-nature ideology of 19th century French poets like Charles Baudelaire, who wrestled with the fascinations and problems of technology in a newly industrialized Paris. Baudelaire dedicated an essay in his 1863 book “The Painter of Modern Life” to the power of makeup, and in particular the way in which creating beauty revealed a greater fundamental truth about the world.

“Everything beautiful and noble is the result of reason and calculation,” Baudelaire wrote. “Crime, of which the human animal has learned the taste in his mother’s womb, is natural by origin. Virtue, on the other hand, is artificial, supernatural.”

RELATED: Can witches and consumer culture coexist? (COMMENTARY)

This same ideology holds true across various pockets of millennial culture. Our techno-utopian obsession with “life-hacking,” in which we perfect ourselves through meditation apps and Fitbits; our self-projections as perfect people on social media; our obsession with witchy glamour: It all comes from our sense that we have the right, even the obligation, to harness our bodies, via technology, to re-create ourselves as the people we want to be.

Who we are, we want to say, is not who we are determined to be by biology, but who we determine ourselves to be.