How will evangelist Billy Graham (1918-2018) be remembered? And is his son Franklin damaging the religious leader’s legacy with his excessive politicizing for the Republican Party and Donald Trump?

How will evangelist Billy Graham (1918-2018) be remembered? And is his son Franklin damaging the religious leader’s legacy with his excessive politicizing for the Republican Party and Donald Trump?

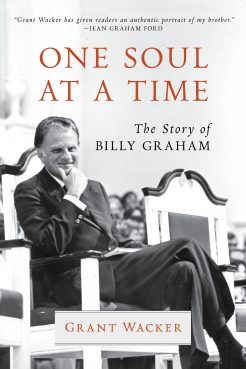

In the new biography “One Soul at a Time,” historian Grant Wacker, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, builds on his previous work about Graham to explore the man behind the legend, and positions his six decades of ministry within the larger contours of American religious history. It’s a great read.

I talked with Wacker recently. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You already wrote “America’s Pastor,” a definitive religious biography of Billy Graham. Why did you want to write “One Soul at a Time“?

Well, my wife assures me this is the last word I will ever write about Billy Graham if I want the marriage to persist, and I do! So this will be the end.

It was rewarding to go back over a project that I started off years ago as the more academic study of Graham in America, and then reconceived as a narrative that focused on the man himself. It gave me a chance to integrate some of the research that my students had done.

It was satisfying in that I was able to bring in new scholarship, and also to change my mind about some aspects of Billy Graham. I became more aware of his complexity, that he was a truly great man but that he also had flaws and imperfections. This is what happens: Great men and women are always deeply flawed people as well.

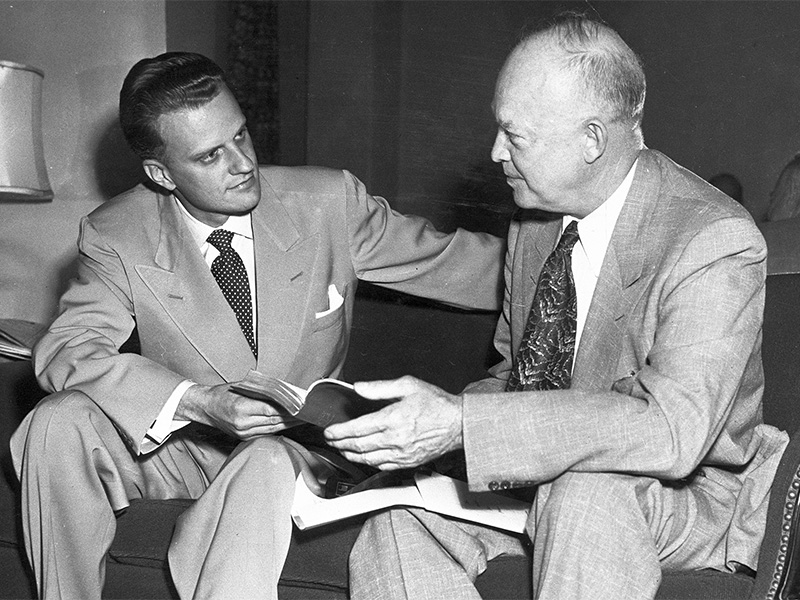

Billy Graham and President Dwight Eisenhower in an undated photo. Photo courtesy of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association

What were some of those flaws?

First, the strengths outweigh the flaws, greatly, or else I would not have spent so many years of my life working on him. Would you write about a person that you fundamentally disliked, or thought had done great harm? For me, the answer is no: Life is limited, and I’ve only got so many hours. I fundamentally like and admire Billy Graham and think he was a great man. It struck me, the more I worked with him, that what was most attractive for me about Graham was how people’s lives changed positively because of him. Wherever I went, I’d get the same story over and over, of ordinary folks telling me, “My life was off the rails, and then I saw Billy on TV, or I went to a crusade, and it changed my life.”

What I found hard about him, first, was his evasiveness. If you like him, you can say it was “adaptability,” but if you don’t like him you see it as an inability to take a stand on important issues. He uttered so many qualifications on so many issues that it’s troubling. You want him to just drive his stake in the ground and stand by it. If you like him, you say he was irenic. If you don’t, you say he was a chameleon.

The second, which is related, was his susceptibility to glamour and power. One of his associates said it very well: Billy was like a cushion who bore the imprint of the last person who sat upon him. He was susceptible to people who were famous and rich. That was the heart of his now-notorious private conversation with Richard Nixon about Jews controlling the media. There was not an anti-Semitic bone in Billy Graham’s body. He was being obsequious to Nixon.

And then, closely related, would be the name-dropping. The times I was with him, it would be instant. Why would he want to do that? He’s Billy Graham! He doesn’t have to establish his credibility with us by telling us about Gorbachev, or Nikita Khrushchev or Frank Sinatra.

But on the other hand, what came through was the sincerity, the integrity. People constantly press me on this question of the Graham Rule. There never was a hint, no matter how hard people pushed on it, that he ever veered away from that rule in his private life. And that takes a lot of strength.

Historian and author Grant Wacker. Courtesy photo

Will there ever be another Billy Graham? Or has the culture changed too much, become too fractured, for one person to carry that whole mantle?

I do not think that there will ever be a single person who will fill that role. The culture has changed; the media has changed. Graham was an artifact of the second half of the 20th century. As the century has moved away from us, I can’t see anyone else emerging. There are also the confrontations that have emerged from (his son) Franklin Graham, and that is clouding the picture.

Having said all that, when he was asked this question, he said: “Yes, there will be a thousand Billy Grahams, and none of them will have heard my name. A lot of them will be pushing bicycles through jungles.” What he meant was that his message would endure.

And I like to think that’s true. I mean, I’m an evangelical. The most fundamental message — that of redemption and hope — will endure and other people will carry it.

RELATED: Franklin Graham on impeachment: ‘Our country could begin to unravel’

President Donald Trump speaks to the Rev. Franklin Graham as they attend a ceremony to honor the late Rev. Billy Graham in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, on Feb. 28, 2018, in Washington. (Chip Somodevilla/Pool via AP)

You mentioned the way Franklin Graham is “clouding the picture” of his father’s legacy. What do you mean?

I fear Franklin’s politicizing of the evangelical message. I do think that Franklin himself does a lot of good with Samaritan’s Purse and humanitarian organizations, and that part of his work will help to sustain the legacy. But he has politicized the message in a way that his father, at least in his later years, would find abhorrent, and that aspect of Franklin Graham’s work will harm the legacy.

How will Billy Graham be remembered?

He was complicated, and he also changed over time. That’s another reason I admired him enough to give him years of my life. He changed. He was able to account for new data. The most striking change was in how he felt about communism. By the early 1980s, he had made a dramatic change to help all nations get along.

And he was criticized for it. George Will said, when Billy Graham came back from Russia in 1982, that Graham was America’s most embarrassing export. But Graham thought the Soviets and the Americans were like little boys playing with matches in a tub filled with gasoline. He made major attempts to depoliticize in those later years. He fell back into political comments in later years, but at least by then he knew the danger.

So I hope people recognize that he changed, and also that he kept his personal moral life straight. What will survive about Billy Graham is the deeper message about the possibility of a new life, and the importance of faith, repentance and keeping your priorities straight.

I was intrigued by new research in the book that shows how Billy Graham’s sermons changed over the decades. His early preaching had a lot of Old Testament quotations, but he became far less “fire and brimstone” in his later years.

That fact came from curators at the Museum of the Bible, Anthony Schmidt and Allison Brown. They crunched the numbers on the sermon texts, which we can do now that the sermons are digitized. And what we find is that Graham became remarkably more inclusive over time.