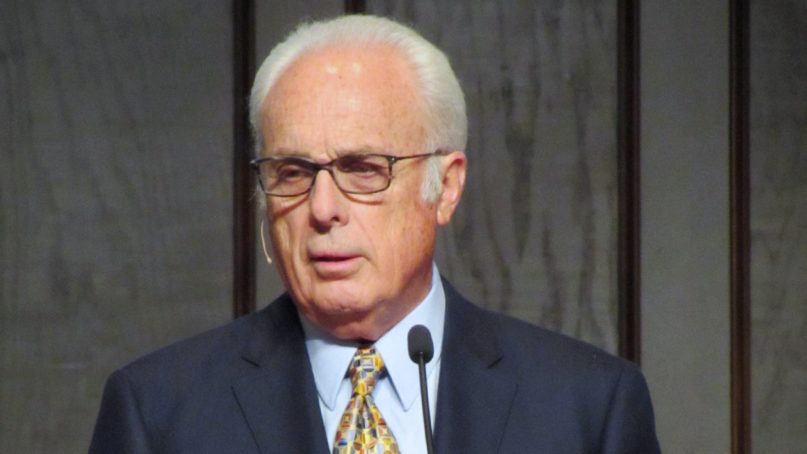

(RNS) — In the past two weeks, a video of the evangelical pastor and radio host John MacArthur, in conversation with two other male panelists at a conference at MacArthur’s Grace Community Church in California, has caused quite a stir in Christian circles.

In the first minute of a seven-minute recording, MacArthur is asked for a pithy response to the name Beth Moore, herself a conservative Christian author who has recently been in hot water with male leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention for speaking engagements that border, in their minds, on preaching.

“Go home,” said MacArthur.

Women, specifically white women, were up in arms.

RELATED: Accusing SBC of ‘caving,’ John MacArthur says of Beth Moore: ‘Go home’

My views are exceedingly different from those of the conservative Calvinist MacArthur, beginning with his theological framework, which would say that my own presence in the pulpit is not biblically warranted. I was not surprised by what I heard on the recording.

I was surprised, however, by how many people were horrified by what they heard. Taking it a step further, I was deeply disappointed that the only thing that sparked widespread outrage was MacArthur’s comment about Moore.

Later in the recording, MacArthur criticizes a suggestion that Latinos, African Americans and women should henceforth be necessary members of Southern Baptist Bible translation committees. He also objects to a resolution agreed to at the Southern Baptist Convention’s 2019 national meeting that deems intersectionality — the theory, developed by Black feminist scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, that describes how overlapping social identities create interconnected systems of oppression — as a useful tool for biblical interpretation.

John MacArthur, center, speaks at a panel discussion at the “Truth Matters” conference at Grace Community Church in Sun Valley, California, Oct. 18, 2019. Video screengrab

The infuriated white feminists had heard one part of the conversation and left. In fairness, many who were infuriated by the recording shared that after MacArthur had dismissed Moore they were too disgusted to continue to listen.

But this is where the dis-ease in my spirit began: So many women in my life, women I know and love, continued to listen but didn’t lean in. Because if they had, they would have heard a man go on to attack diversity, intersectionality, culture — and me. Because I embody diversity, and intersectionality is a constant reality for me.

RELATED: Rozella Haydée White: ‘Revolutionary’ relationships can heal the world

I’ll never forget the first time I learned that my body and my experience as a Black woman mattered to God. I was sitting in a womanist theology class at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia (now United Lutheran Seminary). The professor was lecturing on “Sisters in the Wilderness,” the seminal work by Delores Williams that explores the life of Hagar as a prototype for Black women’s experience of the world.

Have you ever had a moment in your life where something clicked? When you recognized a deep-seated truth that you maybe knew but didn’t quite believe? When things started to make sense even as they led you to more questions? My seminary experience provided these moments. Every class, every assignment, every professor, every conversation. They all stirred me to life and led me to uncovering truths — things that were true in that they brought about restoration, healing and wholeness of my heart, mind, body and soul.

These truths led me to connect with a God who expansively shares love and grace, a God who calls us to the work of co-creation, liberation and sustainability. I came to understand and experience truth as always life-giving. It is never death-dealing. For the first time, I recognized that who I was absolutely mattered to God. My faith, my religious convictions and my theological frameworks could no longer be divorced from my embodied reality.

Womanist theology in particular led me to see my life as a valid lens through which to understand and interpret my Christian faith. I am a practical theologian by training, one who begins with humanity’s experience as a starting place for interpretation.

This is only one theological avenue used by scholars. Biblical theology, historical theology, ethical theology, systematic theology and dogmatic theology all offer valid starting points to engage in the study of God. But as a practical theologian, I am concerned with the intersection of the biblical narrative with the experiences and practices of humanity.

What I know from my work is that it is a fallacy to believe that objective study of the Bible and of faith is possible, that we don’t bring our understanding of self and our own biases to Scripture. Indeed, it has been argued that objectivity is in and of itself a mark of white supremacist culture, as it leads us to believe that there is only one worldview that everyone subscribes to.

It only takes time spent in different cultures and in relationship with people from varying backgrounds to know that there is not a singular story of anything. Everything is viewed through the lens of our experiences and I believe that God designed it this way. God not only desires diversity; God is diversity: In the Trinity we encounter a God who is three persons, a God who is composed of diverse characteristics and creates humanity in this very image.

Diversity is always a gift. It allows us to experience the fullness of God that would otherwise be limited to our own worldview. Our lived experiences and embodied realities invite us all to turn to wonder and curiosity as we imagine what we have not yet learned — and who, in the words of Sikh activist Valarie Kaur, we have not yet tried to love.

Instead, MacArthur’s statements revealed that he considers my experience, my life, to be at best irrelevant, and at worst an abomination when it comes to the interpretation of the faith.

Women who registered outrage only on behalf of Beth Moore did what white women have been doing for centuries: took the part that impacted them most and left their Black sisters in the struggle to fend for ourselves.

In this moment, their cries for diversity seem like a passing fad. They showed that they have never truly committed to and connected with undoing the totality of what needs to be undone. They ignored my reality as if it’s not as important as theirs.

This is a glaring sign of privilege — turning away from that which you don’t want to hear and only taking up arms for that which impacts you immediately.

As long as any of us only focus on our lived experience, we do a disservice to who God is and how God calls us to be in relationship. We must constantly ask questions and be curious about everyone’s experiences.

Author Rozella Haydée White. Courtesy photo

I am not interested in the tokenization of people in the name of nurturing diversity. I am prejudiced toward and passionate about justice that deconstructs all oppressive beliefs and dismantles ideologies, systems and structures that perpetuate interlocking systems of oppression. My life and the lives of those who have always been on the margins are at stake.

(Rozella Haydée White is the author of “Love Big: The Power of Revolutionary Relationships to Heal the World” and is a coach, creator and consultant focused on nurturing life-giving love in this world. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)