(RNS) — This weekend about 10,000 religion scholars from around the world gathered in San Diego at the annual conference for the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature.

I share this reflection in the spirit of our continued work to decolonize our field and to decolonize our world.

My favorite thing about the conference is catching up with friends in the field, professors, classmates and colleagues alike. I also enjoy meeting new friends and colleagues who share similar interests.

This year, however, I had a couple of interactions that left a slightly bad taste in my mouth. During the conference, I met two new people who questioned the appropriateness of my teaching Buddhism.

“Isn’t that a conflict of interest?” one of them asked.

“But you’re not even Buddhist!” the other one exclaimed, before offering a quick laugh.

Here’s the thing. There are many people in our field who do not teach the religions they practice or that are associated with their family background. It’s actually a norm in our field: One can study and teach a tradition as an insider or an outsider. Where we stand in relation to religious traditions does not preclude our ability to study them.

This is not to say, though, that our relationships to these traditions don’t affect how we see them. Of course they do. We each have our own life experiences that inform how we see and understand these traditions. It’s reasonable to assume that a devout Buddhist would view the life of the Buddha differently than I do as a practicing Sikh. Or that a Christian would have a different perspective on the Quran than a Muslim.

When it comes to the study of religion, both of these perspectives, the outsider’s and the insider’s, have important insights to contribute.

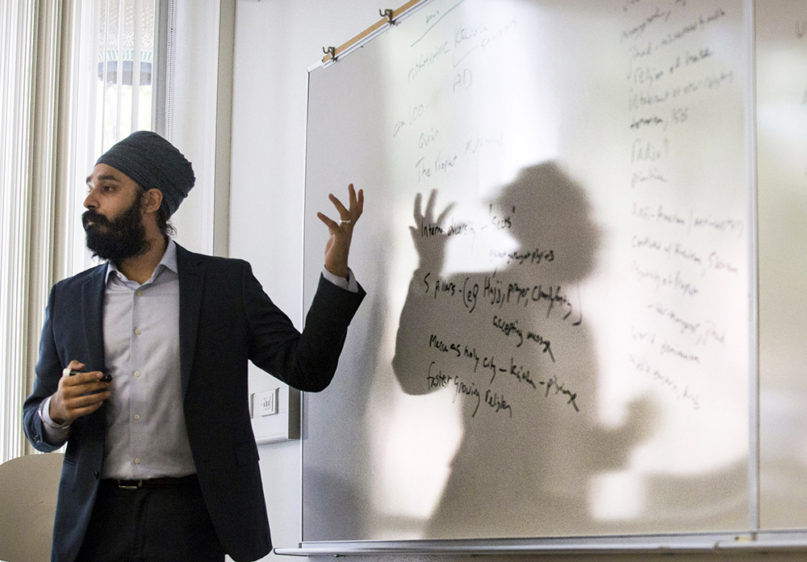

Simran Jeet Singh teaches at Trinity University in San Antonio on Jan. 12, 2017. Photo courtesy of San Antonio Express-News/Ray Whitehouse

Moreover, these perspectives are more complex than the simple binary of insider vs. outsider. This is easy to understand when we remember that not all people of a certain group think the same. Just as there is diversity of opinions within groups (e.g., Americans, Muslims, Democrats), there is diversity of perspectives among insiders who study and teach a religious tradition. The same is true for outsiders as well.

Why is this the case?

A simple answer is that each of us has our individual, complex formations that are uniquely our own. What we have encountered and experienced in life has shaped the way we view the world, independent of the boxes we check on a census form. All of that affects how each of us interprets and engages with the world around us, and the universe of theories and beliefs of our own and others’ faith.

Scholars refer to the individual perspectives as our “subjectivities,” a fancy way of saying that there is no such thing as absolute objectivity as it pertains to the study of religion (and maybe anything else).

So if scholars understand this, where does the idea of objectivity come from? How does that relate to fellow religion scholars being shocked by my teaching Buddhism? And what does that tell us about the state of the field?

It might help to know that the study of religion began in Western Europe as part of the colonialist enterprise.

One of the prevailing arguments then was that non-Western societies (the “Orientals”) had not yet unlocked scientific thought and therefore had not yet accessed rationality. They were incapable, therefore, of thinking objectively. And if they could not be objective, then how could they possibly engage in a study of religion that was unbiased?

Simran Jeet Singh speaks with students during his class at Trinity University in San Antonio on Jan. 12, 2017. Photo courtesy of San Antonio Express-News/Ray Whitehouse

This double standard held that Christians could reasonably study Christian traditions because they had access to rationality. But Hindus could not reasonably study Hindu traditions because they lacked rationality.

The only solution, then, was that only those with access to scientific thought could “reasonably” study these uncivilized and barbaric cultures.

This is how Western Europeans came to establish the study of religion, create the norms for the field and become its sole gatekeepers. This outlook also played a significant role in justifying the violent colonization and imperialization of the “inferior and irrational Orientals,” or white supremacy.

Over the past century, the myth of pure objectivity has been rejected and abandoned. Scholars across the humanities today understand that we each have our own unique perspectives – our subjectivities. This is especially important in the study of religion, where so much of what we study goes beyond the realm of science and rationalism.

Despite this progress, however, the legacies of colonialism live on. The field remains predominantly white, and it is typical to have white scholars of religion teaching traditions as outsiders.

By and large, my professors of South Asian religions throughout my own studies at Trinity University, Harvard University, and Columbia University were predominantly white. Of the four primary advisers I have had at each of these institutions, all of them have been white. All of them, my professors and advisers alike, have been wonderful scholars and mentors. I adore them immensely, and I want to be clear that this is not an indictment of them or even of any single person in the field.

Rather, I am speaking to the legacy of colonialism in religious studies and why it is that someone in the field would be surprised to hear that I, as a practicing Sikh, would be teaching Buddhism.

I received comments like these often while teaching Islamic studies in Texas, but typically these would come from people outside the academy who knew little about the study of religion. It hit differently this weekend when I received comments about teaching Buddhism from two colleagues within the field.

Were these two being malicious with their comments? I don’t think so.

But would they have made the same comments if I were a white scholar? Probably not.

I wasn’t particularly hurt by these comments, but I do think they are problematic. They illustrate the continuing legacy of racist, white supremacist and Orientalist attitudes in scholarship. The colonialist double standard remains alive and well.