(RNS) — Thanksgiving week began in mourning for the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago and many black Catholics, as news came that the Rev. George H. Clements passed away on Monday, November 25. Only the second black priest ordained by the Chicago archdiocese, Clements had a profound impact on the American Catholic Church, the city of Chicago and countless lives across the country in his more than 60 years of service.

Headlines linked him to Martin Luther King, our touchstone for the civil rights era, but Clements is better understood as a black Catholic transformed by Black Power, a man who helped create space to be both “authentically Black” and “truly Catholic.”

Certainly, Clements was present at King’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, along with parishioners from St. Dorothy Catholic Church in the Bronzeville neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. He answered King’s call to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, for voting rights in 1965. But he was revolutionized by King’s assassination in 1968.

RELATED: George Clements, Chicago priest known for adopting sons, dies at 87

When asked “When did you first think of yourself as black and Catholic?” he answered with the clarity of a conversion story. “I can pinpoint the exact moment. April the 4th, 1968, a bullet whizzed through the head of Martin Luther King. I looked in the mirror and I said from now on, I’m gonna be a Black man.”

He was not alone. King’s assassination ignited a decade of activism and institution building known as the Black Catholic Movement. Black nuns, priests and lay people declared the American church a “white racist institution,” experimented with new ways of worship and fought for black self-determination in the predominantly white church.

Clements was dear friends with the charismatic young revolutionary Fred Hampton and came to be known as the honorary chaplain of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, headed by Hampton and Bobby Rush. Clements helped found the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League, which fought to reform racist policing practices in the Chicago Police Department.

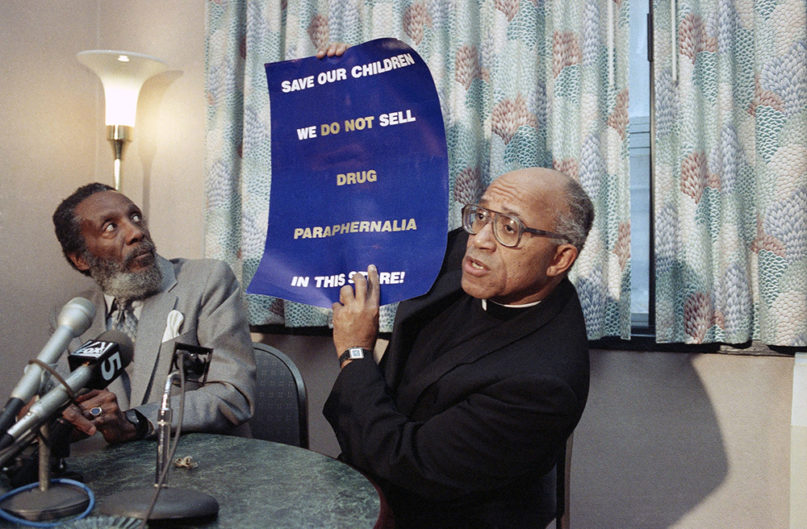

In a Jan. 22, 1990, file photo, Dick Gregory, left, looks at a sign held by the Rev. George Clements, of Chicago, during a press conference in New York, to introduce their campaign to combat drug use in Times Square. Clements, the Chicago priest whose civil rights and social justice activism prompted the making of a movie about his life, died Nov. 25, 2019, in a Hammond, Indiana, hospital, according to the Archdiocese of Chicago. He was 87. (AP Photo/Frankie Ziths)

In return, the Black Panthers allied with black and white Catholics in protest when the archbishop refused to promote Clements to pastor of his predominantly black parish in 1968. Together they occupied Catholic churches in the middle of Mass, celebrated “Black Unity Masses” and demanded black control of Catholic institutions in Black neighborhoods. With their help, Clements won the pastorate of Holy Angels parish, which he would transform into one of the most prominent parishes in the country.

Clements’ life story is emblematic of the long history of black Catholics in the United States. His father hailed from Lebanon, Kentucky, in the state’s “Holy Land” region settled in the 18th century by white and enslaved black Catholics from Maryland. These enslaved black Catholics demonstrated an “uncommon faithfulness,” as the theologian M. Shawn Copeland has put it, maintaining their membership in the church in the face of the violence of enslavement and later segregation inflicted by their white coreligionists.

While Clements’ father was not especially devout, his grandmother was. When Clements’ family moved to Chicago in the midst of the Great Migration, the matriarch made it her business to ensure the Clements children kept their family faith, traveling frequently between Kentucky and Chicago to do so. She convinced George’s mother to become Catholic, to baptize her children, and to join the vibrant Bronzeville church, Corpus Christi. This was the start of the path that would lead to Clements’ ordination in 1957.

Ordained before the Second Vatican Council changed so much about Church life and identity, and with his own identity forged by the resurgence of late 1960s black nationalism, Clements cut a complicated figure in a complicated time. He embraced Black consciousness but never gave up the more “traditional” pieties of pre conciliar Catholicism. He incorporated Black nationalist politics and aesthetics into his parish but insisted on many of the same strict rules and regulations for Catholic school families that white priests and nuns had reinforced in his youth.

He repeatedly challenged Church authority, frequently getting into fights with his archbishop — the first was ignited in 1969 when Holy Angels replaced a shrine to St. Anthony of Padua with one to St. Martin Luther King. Yet Clements reinforced the patriarchal power of the priesthood again and again throughout his career as well, which we can see in some of the masculinist assumptions that governed leadership in his parish and parochial school.

In August of this year, Clements was accused of sexually abusing a minor in 1974. The Illinois Department of Children and Family Services has ruled the accusation unfounded, though the archdiocesan investigation remains open. Certainty can be elusive in cases like Clements’ and may remain so for years to come.

Nevertheless, this accusation, as does any proper recognition of Clements’ life, calls Catholics to wake up — yes, even as we rightly recognize Clements’ significance. It calls us to wake up to the fact that black boys and girls have been (and remain) especially vulnerable to abuse and violence at the hands of Catholics, precisely because they’ve been historically marginalized by the Church.

It insists that we face the fact that some of the more notorious Catholic abusers in Chicago were black priests, one of whom succeeded Clements at Holy Angels. The accusation against Clements may prove to be unfounded. It may not. We may never know one way or the other. But other accusations made by black girls and boys, by black women and men, against both black and white priests, are certainly not.

What we know about Clements is that his life resists easy summary. Having founded the One Church-One Child program, which sought to find homes for orphaned black youth, Clements adopted his first son in 1980, becoming the first U.S. priest to do so. He is survived by his sons Joey, Friday, Stewart and Saint.

He is more figuratively survived by black Catholics across the country, hundreds of whom flew to Chicago in 2017 to celebrate the 60th anniversary of his ordination and to testify to the countless lives he touched. (As a white Catholic, I, too, entered the ranks of those countless lives in interviews, phone calls and letters exchanged in recent years.) On the day he passed away, the Rev. Maurice Nutt, a black priest and theologian, reflected that “Black Catholics owe him a debt of gratitude for his prophetic voice and radical discipleship.”

(Matthew J. Cressler is an assistant professor of religious studies at the College of Charleston and author of “Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration.” He is on Twitter @mjcressler. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)