(RNS) — Barbie has always filled the role that we now know as an Instagram influencer. In the ’60s she was a “swinger” in a Carnaby Street cape; in the ’80s she adopted aerobic instructor togs; by the ’90s she was pantsuited up to run for president. With her impossible physical proportions that no gym could possibly provide, and her artificial hauteur, she showed the way to the ideal life through unattainable glamour.

But last week, Mattel announced a new iteration, “Self-Care Barbie,” that transforms the company’s 61-year-old manikin into a being defined by the moral effort of such perfection. Created in partnership with the meditation app Headspace (which has also collaborated with Weight Watchers on the diet company’s wellness-focused rebranding), Self-Care Barbie, according to Mattel’s press release, informs us that the doll is designed to “introduce girls to self-care through play.”

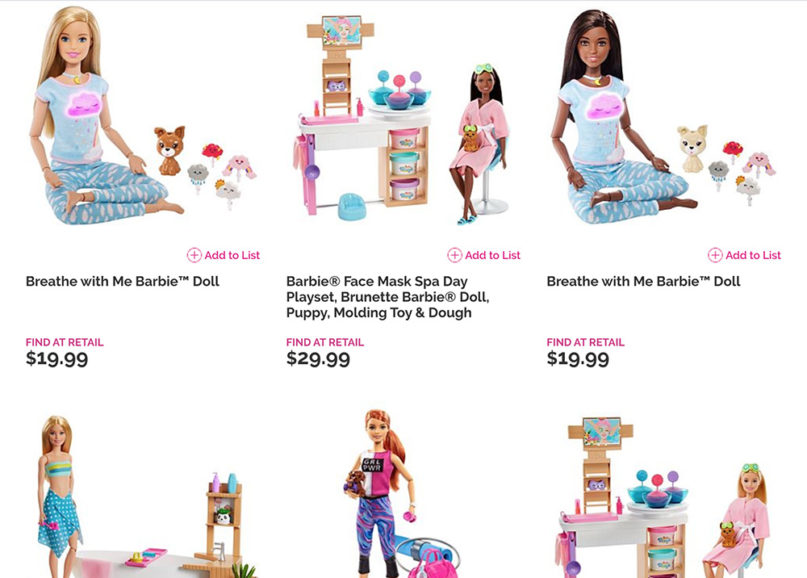

Promotional photo for the new Barbie Wellness dolls. Photo courtesy of Mattel

There are actually four dolls to add to one’s shelf in the Self-Care collection. There’s a “spa doll,” who comes with a robe, and plenty of magazines to read, as well as adorable cucumber sunglasses. There’s a “fitness doll,” whose form-fitting gym kit comes with a protein bar that her plastic esophagus is unable to consume. There’s a “pampering doll,” who gets bath products and a loofah.

Finally, there is a “wellness dream” doll, who has a pillow and sleep mask. (To be fair, my personal wellness dream involves sleeping until noon). All dolls come with adorable puppies. (Also, in my mind, a reasonable form of self-care).

The press release goes on: “The collection teaches girls daily routines that promote emotional well-being and includes three key themes: meditation, physical well-being, and self-care; because Barbie knows to be one’s best is to give yourself the best care.”

For years, marketers of adult traditional glamour — high-end gyms like Equinox, for example — have been spiritualizing their come-ons by promising “self-care,” with language that indicates wholeness and mental stability, rather than the traditional (and Barbie-inspired) chiseled body. Now Barbie is shilling this same combination of wellness and consumerism to children.

She’s also, for the first time in Barbie history, making implicit demands of the children who play with her: not merely in some abstract, idealized future adulthood, but in the present.

Children have always been invited to see their own futures in Doctor Barbie or Judge Barbie. But “spa days” and “pampering” are things children can do in the here and now: Any child with an iPad (and permissive parents) can download Headspace and start meditating.

It’s telling, too, that Barbie’s aspirational qualities here are neither those of beauty nor those of career success, but rather about internalization and quasi-spiritual purity: Barbie is good at taking care of Barbie. The fantasy children indulge in is one in which they are playing at playing: fantasizing about leisure time, and honing the skills and values that such a fantasy suggests.

A variety of the new Barbie Wellness doll options. Screengrab via Mattel

Barbie’s new perfection is grounded not in her perfect plastic proportions, nor in her sheer essence as the Ur-Feminine, but in the ritualistic oblations one can make, through play, toward the Self-Care Experience. To “be your best,” to “be as good as Barbie,” means to go to the gym, to go to the spa, to spend time and money on practicing the necessary markers of Best Self-ism.

The fact that Mattel is partnering with Headspace — a for-profit app that commodifies the practices of Zen meditation in order to make them more palatable to, say, a stressed-out commuter on his or her way to work — only intensifies the uncanniness of this particular project. These dolls aren’t just toys. They are, in Mattel’s own words, teaching tools: designed to initiate young girls in the the ideology of self-care as a moral duty, and (often expensive) forms of pampering and the intuitional inwardness they engender as inherent goods.

Of course, dolls have always been teaching tools. The ubiquitous “baby dolls” of the 1950s — no less restrictive in their way — taught young girls to play at the role of being wives and mothers. Today’s self-care Barbies do the same thing: teaching girls that the role they were born to play is that of their Best, and most pampered, self.