(RNS) — As a Sikh American who wears a turban and beard, I know firsthand what it’s like to be made invisible. Ours is one of many communities that have been marginalized and underrepresented for as long as we’ve been established in the U.S.

Of all the places from which we have been excluded, however, one might expect we’d be included among those who work to build interfaith communities. Yet so often the practitioners of the world’s fifth largest religion are an afterthought even when it comes to interfaith outreach, by politicians, corporations and on campus.

The reasons for this have to do with the history of interfaith work, an enterprise that presents itself as an even playing field without acknowledging its historic origins in Christianity and Christian supremacy. When we understand this history, it becomes far easier to observe how and why Christianity normally dominates the discourse, and all other traditions are decentered.

Being privy to the politics of interfaith, I wasn’t terribly surprised when I saw the composition of the Elizabeth Warren campaign’s interfaith advisory council, which she announced in January. The group consisted of more than 100 Christian ministers, one rabbi and one Buddhist sensei. This lineup, I thought, simply reflects the Christocentric nature of nearly every interfaith effort I’ve known.

What I didn’t expect is that I would, a month later, accept an invitation to join Warren’s interfaith council.

My involvement began, ironically, with my decision not to publicly flame the senator online for the composition of her council, as others did, noting in particular the lack of Muslims or Catholics. I held back because what I saw in her initial announcement didn’t comport with what I had seen from her campaign or her tenure in public office to date. She had consistently demonstrated a thoughtful commitment to inclusion.

It also didn’t fit with how Warren has talked about her own worldview. When asked about how her Christian faith shaped her politics, she has spoken of her deep-seated beliefs that every human being is valuable and that people of faith are called to serve the most marginalized and most vulnerable. She has acted on these beliefs, too, lifting up these communities through her political efforts and her proposed plans.

RELATED: Meet the pastor who prays over Elizabeth Warren before every debate

Warren has been so steadfast to her commitment of inclusion that the exclusion of multiple communities from her council seemed to me a complete anomaly. She had earned my trust, and I wanted to give her the benefit of the doubt. But I also wanted to know more. So I reached out to the campaign.

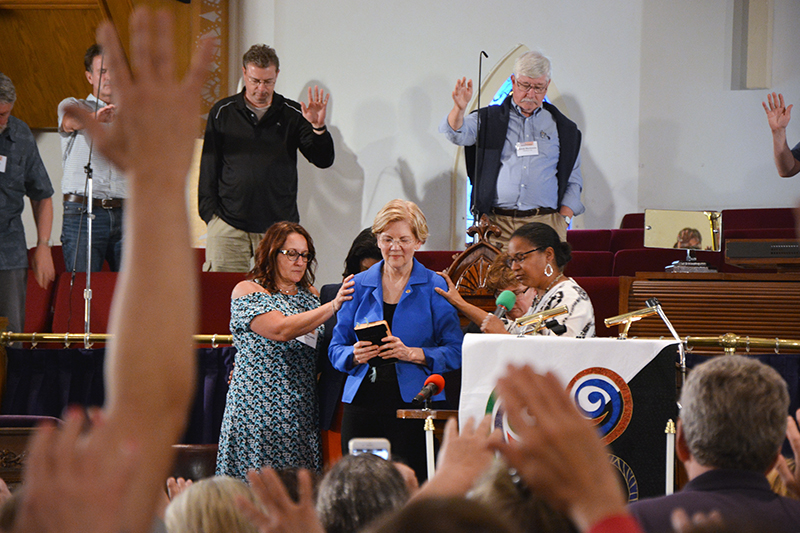

Attendees pray over Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, during the Festival of Homiletics at Metropolitan AME Church on May 21, 2018, in Washington. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

What I learned made sense — she has a number of supporters from diverse backgrounds, including various religious groups. The campaign had been reaching out to and working with these communities from the outset, hosting calls and virtual roundtables with people from these communities. But many faith leaders were more invested in advising the campaign than publicly discussing their involvement.

Warren isn’t the only candidate with a sincere, long-standing commitment to those who are the most marginalized, nor the only one who had a vision for large-scale structural change. But in Warren I see an understanding of intersectionality that distinguishes her from the field. Her articulation of racial justice, reproductive justice, financial justice and climate justice consistently speak to issues of class and race and gender and sexual orientation. Seeing someone with such a nuanced understanding of the problems before us gives me hope for our future.

I also see a level of humility in Warren that is rare in politics. Her inclusive vision tells me that she doesn’t think her way is the only way, and her constant willingness to listen indicates that she doesn’t think she has all the right answers.

Not least, I was lured by the way her campaign has handled the negative response to its announcement of the interfaith advisory council’s relative homogeneity. After being blasted, she listened to supporters who offered constructive criticism. The way she learned from a misstep has made me trust Warren more, not less.

I had multiple conversations with people on Team Warren and I was pleased to learn that her team had been working proactively with other religious minorities as well — Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims — and that members from these communities will also be represented on the council.

We hear a lot these days about why representation matters and how much it means for groups who are historically underrepresented. When we view it through the lens of power and privilege, it’s clear why Warren’s historic inclusion of Sikhs as interfaith advisers is no small thing for Sikhs, and why it’s significant for other communities who are being welcomed into spaces from which they are typically excluded.

Their inclusion is part of a larger process through which those who have been disenfranchised have an opportunity to build community power and continue the march toward equity.

For people used to being pushed to the margins, this progress is no small thing.