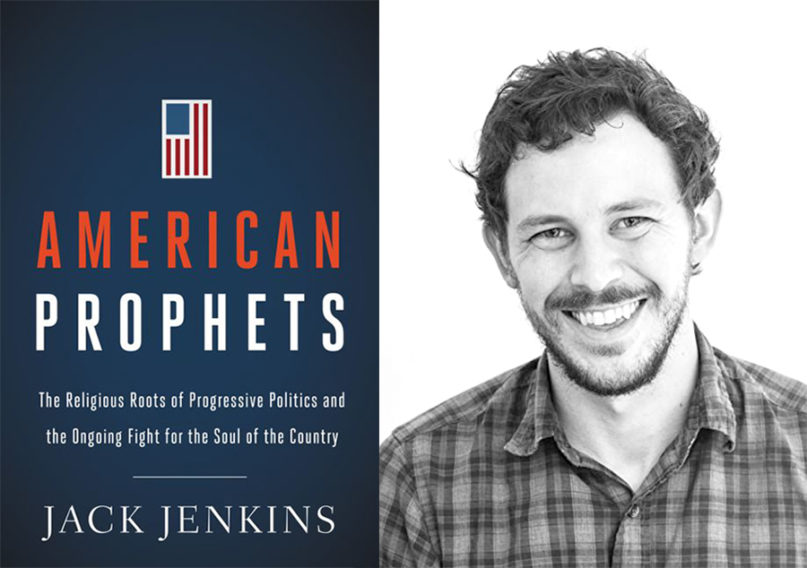

(RNS) — The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book “American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country” by author and Religion News Service reporter Jack Jenkins. The book, which publishes on April 21 with HarperOne, offers a sweeping look at the modern Religious Left, uncovering untold or long-ignored stories of how faith-rooted liberals have made a lasting impact on contemporary progressive causes. The text below is adapted from its fifth chapter, which focuses on the intersection of religion, race, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

* * *

The pulpit the Rev. Traci Blackmon approached that night wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. It was attractive, but in a functional way: wooden, unassuming, accented with a green banner and adorned with a gold cross. It wasn’t all that different from the one that stands in front of the sanctuary at her home church in Florissant, Missouri. If anything, it was smaller. Her vestments were also fairly standard for a Protestant pastor: black shirt, white clerical collar, red stole.

But if you looked closely, there were hints that something about that night was different. The image emblazoned on Blackmon’s stole wasn’t a rising dove or a Jesus fish — it was a raised fist. The pews weren’t occupied by a smattering of sleepy-eyed local churchgoers but packed to the edges with 1,000 or so ecstatic worshippers who hailed from different parts of the country and claimed different faiths, most already on their feet applauding or standing on tiptoe along the faded yellow sanctuary walls. And the tiny flashes of light that would soon flicker in the distance outside the windows weren’t streetlights, but tiki torches held aloft by white supremacists.

It was August 11, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia, and Blackmon was there to talk about race.

“I must just say, this may be the first time that I have been in a standing-room-only church on a Friday,” she joked, sparking peals of laughter from the crowd.

It was a rare moment of levity in an otherwise grim context. The group of Charlottesville residents and clergy gathered at St. Paul’s Memorial Church was one subset of the thousands who had traveled to the sleepy Virginia university town that weekend to muster counterdemonstrations against the next day’s rally.

Originally organized to protest the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in Lee Park at the heart of city, the event had ballooned into a rally for a broad spectrum of right-wing groups that included neo-Confederates, white supremacists and Nazi sympathizers.

Blackmon argued from the pulpit that evening that faith groups simply hadn’t done enough to end the scourge of racism and had “celebrated victory too soon.” Her brow furrowed and her voice serious, the black United Church of Christ pastor of Florissant’s Christ the King Church lamented the failures of the past.

“When violence and hatred are flourishing, it is necessary that love show up,” she said. “When hatred is all around, when violence is the language of the day, when laws lack compassion and churches lose their way, then we who believe in freedom, we who believe in God … we must question: Where have all the prophets gone?”

She then recounted the biblical story of Goliath, comparing racists and their ilk to the camp of Philistines the giant emerged from to face David, the future king of Israel. “Until we close the camp, there will always be another Goliath,” she said, noting that many preachers skip over the most gruesome part of the biblical tale: When the diminutive David defeated his colossal enemy with a stone and a sling, he didn’t simply walk away triumphant.

“The text says that David doesn’t just knock him down and kill him, but David takes his head off,” she said, the crowd nodding solemnly in agreement. “The fact that David takes his head off is a message to the camp: What Goliath has wrought will no longer be tolerated.”

Blackmon insisted that to defeat white supremacy in America — the same horrific ideology that has plagued the U.S. since its founding — people of faith would need to do the same.

“American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country,” publishes April 21, 2020. Courtesy image

“Here I am at 54 years old, coming back because the Klan is still rising,” she said, her voice trembling with passion as she pounded her hand on the pulpit. “The Klan is still rising because we never cut the head off!”

After an outburst of applause, Blackmon clarified that she was advocating not for a physical altercation but a spiritual conflict — one in which faith-based activists would use love-focused methods of religious persuasion and nonviolent resistance. But just minutes after she concluded her sermon, volunteers anxiously informed her and other speakers of an ominous development just across the street: a column of torch-bearing white nationalists had crested the hill and marched down toward the University of Virginia’s statue of Thomas Jefferson. The teeming mob, about 300 strong with many in matching white polo shirts, was screaming racist and anti-Semitic slogans as they walked menacingly around a vastly outnumbered group of student counter-protesters who stood, arms linked, next to the statue.

The congregation in St. Paul’s could hear the hateful chants and see torch flames flickering through the windows. Everyone feared the mass would approach the church next. Worse, police were nowhere to be seen, even as violent scuffles broke out between the racists and the students.

Goliath had arrived.

“They just surrounded the place,” renowned academic and activist Cornel West told me. “It took you back to the old days of the violence-ridden Jim Crow South, where you knew that you were being targeted and that the use of violent power was arbitrary and could come your way. Most of us were pretty shaken, no doubt about it.”

It’s unclear whether the white supremacists descended on the spot specifically to counter the faith gathering or if any left the brawls near the statue to approach the church directly. Compared to the avalanche of reporters that blanketed the town the next day, press coverage during the torch rally was minimal. The only major media outlets in the area were the evangelical Christian magazine Sojourners, which had a representative livestreaming the service to Facebook; a reporter from The Guardian newspaper, who was called away before the rally began; documentary crews from National Geographic and VICE, who were working on longer projects that wouldn’t be released for days or months; and a lone ThinkProgress reporter — Joshua Eaton, an investigative journalist who also covered religion — who left the sanctuary to stand next to the student counter-protesters in the center of the torch rally.

Inside the church, worship organizers were taking no chances. They locked down the building, held the doors shut, and instructed worshippers to stay inside. Unbeknownst to most attendees, the danger was already among them: a white supremacist had entered the church and was livestreaming the event to his followers.

Meanwhile, the congregation tried to drown out the hateful bellowing with hymns of hope.

“We were locked in there for a couple of hours, just singing and praying,” West recalled.

At some point, organizers began escorting people out through the back doors to avoid attracting attention, but Blackmon was defiant. A black woman raised in Birmingham, Alabama — where she witnessed a Ku Klux Klan rally as a child — she wasn’t about to slip out the back. She insisted she and West would leave through the front.

“When I opened the door, all I could see, as far as I could see, were flames,” she said. “People were chanting, ‘You will not replace us! Jews will not replace us!’ And I decided that, this one time, I might go out the back door.”

To the casual observer, people of faith like Blackmon gathering to resist racism is almost expected. The vibrant activism and oratory of religious leaders in the 1960s-era civil rights movement is a story many Americans know well; the image of Jews, Christians, Muslims and other faiths assembling to condemn white supremacy is one that has long been burned into the American psyche.

But that easy assumption belies the complex interaction between religion, race and activism in recent years, particularly within liberal circles and the Religious left. Progressive faith movements have risen to meet moral challenges throughout American history, but that doesn’t mean the periods between are without controversy and missteps — or that the transitions into eras of activism don’t require doing the hard work of reforging connections and reckoning with past mistakes.

And when it comes to race, American faith groups have much to reckon with.

(The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)