(RNS) — For more than half of his life, the Rev. Otis Moss III has sought to find ways to merge the cadence of the sermon with the creativity of movies.

In addition to being senior pastor of Chicago’s Trinity United Church of Christ, Moss founded Unashamed Media Group, which he described as “creating small films we hope will be used to teach, to inform, to inspire and shape homiletics in a different way.

“I believe that films preach,” he said.

On Sunday (May 17), in honor of a young black jogger who was recently killed in Georgia, Moss premiered his latest fusion of faith and film: “The Cross and the Lynching Tree: A Requiem for Ahmaud Arbery.”

The 22-minute sermonic film features Moss preaching in his predominantly black megachurch before stained-glass windows that depict African American and church history. Interspersed between his words are images of a black actor pausing to tie his running shoes, clips of two drastically different movies released a century apart but both titled “The Birth of a Nation,” and footage of persecution and protest.

Moss, 49, is an Auburn Seminary senior fellow known for his commitment to social justice and a minister whose sermons placed him on Baylor University’s list of top 12 preachers in the English-speaking world. He learned film editing as a teenager tasked with cutting “Twilight Zone” episodes so a local Cleveland TV station could include commercials. Citing Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, he says, “My favorite filmmakers were people who were influenced by spirituality.”

The Rev. Otis Moss III records clips for the film “The Cross and the Lynching Tree: A Requiem for Ahmaud Arbery” at Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. Courtesy photo

RELATED: Click here for complete coverage of COVID-19 on RNS

He talked to Religion News Service about his newest project — which was first released in place of his usual sermon — and how he hopes it will educate people of faith, African American parents and clergy who might consider a new approach to their preaching.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to use the format of film to preach about the life and death of Ahmaud Arbery?

One, I started out in film, cinematography in college and thought it was one of the best mediums to communicate the challenges we face in America today. The other aspect of it is people learn in different ways. Some are visual, some are auditory, some are kinetic learners. And bringing the element of visual and auditory together reaches more people.

How did you relate the death of Ahmaud Arbery to the late theologian James Cone‘s “The Cross and the Lynching Tree“?

Cone’s book lays out the cross as a lynching event, an innocent person being lynched, executed because of his ethnicity, his location. The perception of Jewish people in the Roman mind connects with the way black people have been viewed in America, and our color has been weaponized by Confederate and antebellum thinking.

Within the first minute of the film you tie the current coronavirus to what seem to be various forms of racism. Why did you make that link?

Racism is a virus. It infects the spirit. It infects the soul. This is nothing new that I’m sharing. Dr. (Martin Luther) King spoke of it in the same manner. Howard Thurman talked about it as being a spiritual infection. Frederick Douglass spoke about racism and white supremacy as a virus that infects the soul. As we are all sheltering in place to recognize the invisible enemy of COVID-19, there is also an invisible enemy that affects our behavior, being racism, privilege, the inability for the heart to be compassionate to people who are different but not deficient.

You also spoke about the “illusion of blackness as a threat.” How would you encourage people, including people of faith, to address that or counter that?

I would challenge all people of faith to become educated about the weaponizing of black skin in American culture. (Scholars like Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Michelle Alexander and Ibram X. Kendi) speak about the ideology and the myth of black criminality, and people of faith must view Jesus as a person who was disinherited, an outsider. His culture, ethnicity and the fact he was a dark-skinned Palestinian Jew was weaponized by Roman culture.

You use the verb “weaponize” throughout the film. Why?

At the turn of the (19th) century, Reconstruction, the myth of black criminality stated, if you see someone who is darker, they are dangerous. Their skin, their skin color is viewed as a weapon because they do not have the intellectual capacity or moral rooting of people of a lighter hue. So our skin was weaponized. The 12-year-old who walks into a room is viewed as 24 and dangerous because years are added to his physical appearance. The person, like myself, who’s 6′-3″ (and) 200 pounds, I have stepped into an elevator and had people clutch their purse, or, in one case, someone screamed when they saw me because my skin had been weaponized.

Stained-glass windows depict African American and church history at Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

RELATED: Religious leaders decry, question death of Ahmaud Arbery after video surfaces

You also list dozens of names, including Ahmaud Arbery’s, who have died. So in addition to being a requiem for him, is this sermon-film about more than one person’s death?

Yes, it is. It speaks about the death of unarmed individuals. It speaks about the death of people who were killed while running while black, eating, sitting, selling something on the corner. We have too many examples of women and men who have been killed, not because of criminal activity, but because of the weight of history.

You recount how historically blacks have been prevented from reading the Bible and from preaching without a white leader present. Is your new film-sermon sort of the opposite of that?

Yes, it is. There has been a myth that has been passed on in America that black faith made black people docile when the historical evidence shows slave owners did all they could to ensure that black people did not read the Bible and did not preach without a white person present to tell them what they’re to say and watch over what they say. And this sermonic film is a historical response to that: the ability to be able to tell our own story in ways our ancestors were not able to tell the story.

You also mention a broader view of sacredness. Can you explain why you included the sacredness of a jogger in that list?

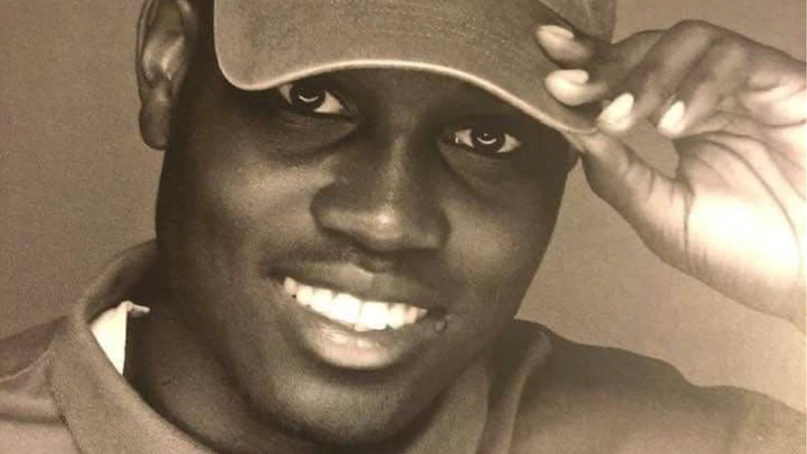

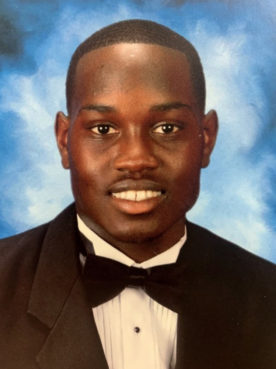

Ahmaud Arbery, in an undated family photo. Courtesy photo

Within black spirituality, all aspects of living are sacred. There is no separation of sacred and secular: singing, caring for your children, working and jogging, which brings us right back to Ahmaud Arbery. The idea of caring for your body is also a sacred act. Within all traditions, your body is a gift that you are to care for because it is the only one that you will receive from God.

What is your advice to black parents who, as you say in this film, wonder if their children will “make it home today”?

You must tell your children the truth without instilling debilitating fear in their heart. Give them the power of truth and also the power of possibility. They have within them the tools to change our democracy. This is what we teach in our household to our children: how important voting is and judges and DAs (district attorneys) and being seen on juries. And learning, leading is critical to changing the world.

But there are some rules you must understand when you step out of this door. Some people will not see you as a frolicking teenager. They will see you as a threat, and you must use your mind and your spirit hand in hand so that you may come home safely.

RELATED: Like father, like son: Black activists tag-team preach on Father’s Day

Do you view the film as a message for a wider audience than African Americans, and, if so, what is it you hope others will take away from it?

Absolutely. The response from the worship service has been astounding, especially from people outside of the African American community. One person shared it gave him language to have a conversation with their children.

Beyond the sermon on Sunday, how do you expect your message to be used?

It’s my hope it’ll be used as a teaching tool: Classrooms, organizations, institutions will use this to talk about America’s original sin being race, racism, white privilege. It will be used to talk about how sermons can be shaped in the 21st century by merging the art of film and the tradition of sermonic presentation together. It will be used to inspire people who feel as if their spiritual tank has been depleted and now they have a little bit more energy, in the words of my father, to just go on a little bit longer.