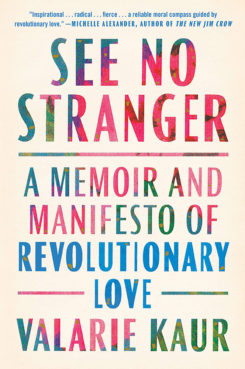

(RNS) — Valarie Kaur, filmmaker, lawyer and civil rights activist, recently added author to her resume with the release of her debut book, “See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love.”

In “See No Stranger,” Kaur draws from Sikh wisdom to offer a vision for living that is rooted in love. Kaur, a precise and emphatic speaker in her popular Ted talk, is at her most vulnerable in this book, sharing the stories of being sexually assaulted and attacked for race and how these experiences led to her activism. It also includes a manifesto for her Revolutionary Love Project, a pragmatic view of how we can make love the motivating principle of our own lives.

I spoke with Kaur recently about her work and her book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you mean by revolutionary love?

Love is revolutionary when it has no limit. We’re seeing this now — millions of people in the streets, risking their lives during the pandemic, grieving, raging and fighting for Black lives. Revolutionary love is seeing George Floyd as our brother, Breonna Taylor as our sister — and showing up in the labor for justice. This is an unprecedented moment in history. I feel immense pain and devastation, and I’m also energized by this revolutionary moment we’re in. This book offers people a guide for how to stay in the labor and last.

“See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love” by Valarie Kaur. Courtesy image

You have a lot going on. Why write a book?

I wrote this book as an act of survival. I’ve been a civil rights activist for almost 20 years, and I was burned out when this president took office. I broke down. I needed to find a way to stay in the struggle. I was given a gift few women who are mothers and activist are given — time off and a room of my own. I pored through all the stories of my life, and the wisdom of the Sikh faith, and the science of human behavior, and the history of social movements, and I saw patterns. I began to call them practices of revolutionary love. This book is about reclaiming love as a force for justice for a new time.

You write about three phases of revolutionary love. Could you quickly walk us through each and explain how they fit together?

The book is divided into three parts: loving others, opponents, and ourselves. I define love not just as a rush of feeling, but as the choice to wonder about others — and labor for others. It means opening ourselves to another person’s story, letting their grief into our heart, and fighting for them when they are in harm’s way.

But if we “see no stranger,” that means our opponents, too. This is hard work! It begins with honoring your own rage. Rage is healthy and normal and necessary when it comes to injustice.

Only when it is safe, some of us may be in a position to listen to our opponents. I’ve sat with white supremacists and police officers and prison guards and abusers, and I’ve learned there’s no such thing as monsters in this world, only human beings who are wounded. Each time I listen, I gain information for how to change the conditions that drive their behavior and begin to reimagine the institutions that authorize their violence. This is long, hard work!

Which brings me to loving ourselves. We need to breathe and push in any long labor in order to last. So loving ourselves is about finding a rhythm in our lives, breathing and pushing and letting in joy, even in the darkest times. Loving only ourselves is escapism; loving only our opponents is self-loathing; loving only others is ineffective. All three practices make love revolutionary.

How has your own background in Sikhism informed the vision behind this book?

Sikhi is the wellspring of my life — and this book. When I was a little girl, my Nana Ji (grandfather) would teach me the stories and songs of Sikh gurus and martyrs and warriors. Guru Nanak, the first teacher of the Sikh faith, called us to a vision of Oneness. To look upon the face of anyone around us and think: You are a part of me I do not yet know. Guru Nanak called for a revolution of the heart.

Valarie Kaur. Photo by Amber Castro

It was always a dangerous call. For if I love you, then I must serve you and fight for you when you need me. The Sikh model is the sant-sipahi, the sage-warrior. The warrior fights, the sage loves, so I saw it as a path of revolutionary love. This book is my attempt to carry Guru Nanak’s call to love in a new time, infused with my own struggles and the wisdom of many others.

But you draw as well from outside the Sikh tradition.

I’ve been profoundly shaped by black thinkers in America — Audre Lorde, bell hooks, James Baldwin, Dr. King. I’ve also been formed and inspired by black visionaries today, especially Michelle Alexander, Bryan Stevenson, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Van Jones. My editor, Chris Jackson, has created a home for many of these authors and invited me into conversation with their ideas.

When you started this book, you can’t have known how it would speak to our current moment.

The book has never felt more urgent. It is about how to stay in the long labor of birthing an anti-racist society. It’s about how to grieve and rage and reimagine together. It’s about how to summon our deepest wisdom in times of massive transition. It’s about how to labor with joy. The choices we make leading up to the 2020 election will determine the course of history, and this book offers a way to lead with love.

What gift do you hope this book gives the world?

In the dark hours, I hope that you can hold this book in your hands as a guide, a meditation, or just a companion. You have a role to play in this moment in history that only you can play. May this book help return you to your deepest wisdom. May it seed pockets of revolutionary love.