(RNS) — It was 11 years ago that Gulruy Asqer began praying for a chance to escape China.

Back then Asqer, a Uighur poet now in Memphis, Tennessee, was living in Urumqi, the capital city of China’s Xinjiang region that is home to the mostly Muslim Uighur minority.

That’s where Asqer says she was first introduced to “the true face of the Chinese government,” as she witnessed the state’s suppression of the ethnic violence against Uighurs that tore through the city in early July 2009, leaving her family living in constant fear that they might be detained or disappeared.

“The whole city was different,” she said, recalling the plainclothes officers who began knocking on doors and investigating members of her own family. “That was the most difficult year of my life. I was so helpless.”

Experts say that month’s unrest and the state’s aggressive response marked a major turning point in China’s brutal crackdown against the Uighur minority.

The unrest began with a student-led Uighur uprising on July 5, 2009. Human rights activists and Uighur eyewitnesses insist the initial protests were peaceful. Violence only broke out, they say, when Chinese paramilitary — called in to quell the riots — allegedly fired live ammunition onto protesters.

Witnesses describe and photographs depict streets with bloodied corpses lying in the streets, broken glass and buildings on fire surrounding them.

Ads around the city were replaced by posters from law enforcement seeking information about and the capture of young Uighur men suspected of involvement in recent protests. Asqer’s neighbor’s sons, high school students at the time, were taken and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

“I could tell what would happen in the future,” Asqer said. “I was so aware that if I just made it to the U.S., I would never return to this bloody land.”

The Xinjiang province in western China where many Uighurs live. Map courtesy of Creative Commons

Discord between the Hans and the Uighurs, indigenous to the Xinjiang region, had been common since the Han-majority government took control of the region after the Communist revolution in 1949.

The impetus for the 2009 protests came in June, at a toy factory in the city of Shaoguan, about 2,500 miles away from Urumqi.

A factory worker posted an unsubstantiated rumor online that Uighur migrant workers had raped Han Chinese women there. Some Han Chinese workers responded by beating Uighur workers in a brutal attack captured on camera. At least two died in the attacks.

When the gory video footage spread online, long-simmering ethnic tensions in Xinjiang rose to a boiling point and spurred the July 5 protests.

“It is a very clear depiction of men being hunted down and beaten to death,” said University of Nottingham historian Rian Thum, who researches Islam in China. “The clarity of that video is what made it so powerful in mobilizing people.”

Peaceful student-led protests for justice soon turned deadly. Young Uighur men rampaged through the streets on July 5, beating and stabbing Hans and attacking Han businesses. For days afterward, Han mobs armed with sticks and metal bars carried out violent reprisals.

And in the weeks and months following, thousands of Uighurs, mostly young men in their 20s, disappeared from the region.

“I now think of it as the beginning of the era of disappearances,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, which published a report documenting the “enforced disappearances” of 43 Uighur men and teen boys detained by Chinese security forces as part of what researchers described as a “massive campaign of unlawful arrests.”

Richardson and other experts on the Uighur crises spoke on a webinar organized Thursday (July 2) by the Uyghur Human Rights Project and World Uyghur Congress to explore how the 2009 events “paved the way from systematic assimilation to today’s cultural genocide.”

“In many ways, that was a pivotal day in terms of ethnic tensions erupting in Xinjiang itself,” said Adrian Zenz, a Washington-based anthropologist whose research helped uncover the vast scale of China’s “reeducation camps” for Uighurs. “No matter who died or who started what … that is when the underlying rupture became visible and ethnic relations were changed forever.”

“Looking back, we see there’s a logical unfolding of a repression that uses whatever means are necessary,” Zenz said during the webinar.

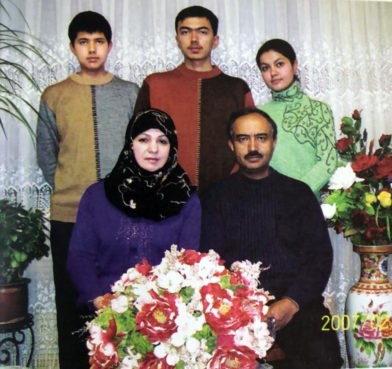

Gulruy Asqer’s nephews, back row, Behram Yarmuhemmed, who was taken to a detention camp in 2016, and Ekram Yarmuhemmed, who is serving a 10-year prison sentence. Photo courtesy of Gulruy Asqer

Zenz described a “great deal of consistency” between the state’s aggressive response to the Uighur uprising and today’s repression of Uighurs. But what’s surprising, he said, is the “speed and intensity” with which this repression multiplied in scale.

“The speed, severity and disproportionate nature of the state’s response is what we’re seeing the downstream effects of now,” agreed Richardson.

In the years since 2009, Asqer’s brother, brother-in-law and two nephews — one of whom participated in the protests — have joined more than a million Uighurs and other Turkic minorities who have disappeared into China’s shadowy network of mass detention camps.

Reports suggest constant surveillance, brainwashing, forced labor, forced sterilization and abortions, and even organ harvesting are likely taking place at a systemic level within those camps today.

Prominent exiled Uighur activist Rebiya Kadeer, the World Uyghur Congress leader whom Chinese officials later blamed for instigating the violence, claimed that month that nearly 10,000 Uighurs went missing overnight after the protests.

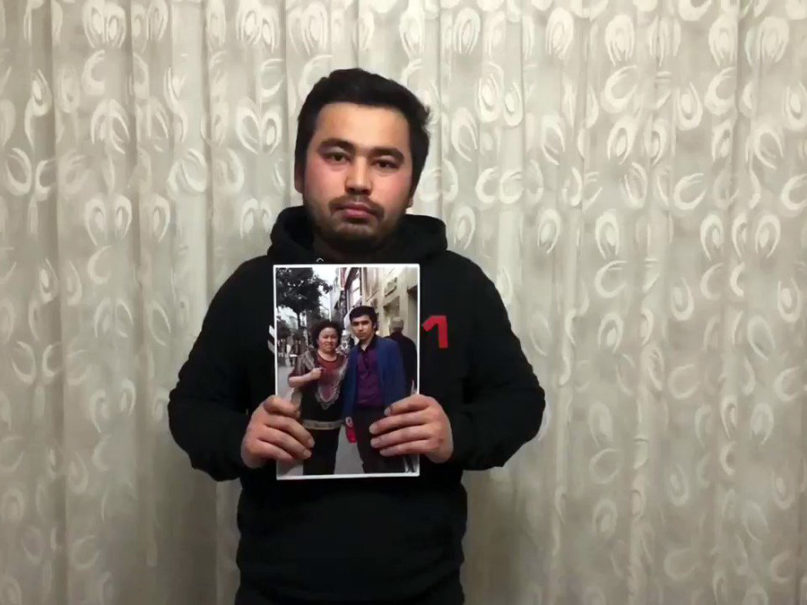

One of the men arrested was a friend of Jevlan Shirmehmet, a Uighur who has lived in Turkey since 2011.

“He told me it was so chaotic that no one knows what’s happening around them anymore,” Shirmehmet remembered. “He saw police arresting people left and right … Then one day I saw from the news that he was sentenced to a death penalty with two years suspension.”

He said the Urumqi riots shocked the Chinese government into “committing the century’s crime against humanity” with its mass detention camps. In 2018, Shirmehmet learned his own family had been detained in China’s camps, though he has since learned that they have been released. Chinese officials told him his mother, 56-year-old civil servant Suriye Turson, had been sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for aiding terrorists. Shirmehmet suspects she was instead being punished for visiting him in Turkey while he was a law student.

“Everyone from 7 years to 70 years old came out to express their anger,” Shirmehmet recalled. “This is (an) outburst of the anger and dissatisfaction that was suppressed for many years toward the unfair treatment, racial discrimination of the Chinese government.”

Jevlan Shirmehmet holds a photo of his mother, Suriye Turson. Photo courtesy of the Campaign for Uyghurs

Beneath the surface, Zenz said, resentment simmered over decades of cultural discrimination, including suppression of Uighur language and religious practice, paired with socioeconomic hierarchy and competition for jobs, as well as demographic changes as Han migrants flooded Xinjiang.

The uprising, Zenz said, “visibly demonstrated the failure of CCP’s ethnic policy of the preceding five to six decades.”

But it was the Chinese government’s silence when Han Chinese people — not just the state, but fellow civilians — killed Uighurs in Shaoguan that finally forced Uighurs to the breaking point, Shirmehmet said.

Chinese officials say that nearly 200 people, most of them Han Chinese, died in what they described as riots “instigated and directed from abroad, and carried out by outlaws in the country in the region.” Another 1,700 people were injured and 1,000 arrested, per government records.

Human rights advocates say those numbers, which cannot be independently verified, obscure the violence and abuses perpetrated by police and Han civilians alike against Uighurs.

Shirmehmet compared the events to the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. While the student-led Tiananmen pro-democracy demonstrations are known globally, grabbing major media attention because they took place in Beijing and because they lasted two months before the government successfully suppressed them, the conflict in Urumqi is not so widely known.

The Urumqi protests were crushed within hours, Shirmehmet said. On top of that, he said, many witnesses of the Tiananmen crackdown are now overseas telling their tale right now. Those who saw the Urumqi massacre “can’t even move from one city to another,” he opined.

The Chinese government immediately responded to the protests by cutting off internet access in Xinjiang until April 2010. When access returned, residents could no longer use global social media such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. CCTV and other forms of surveillance became ubiquitous.

Daily life has been utterly transformed for Uighurs since 2009.

“For Uighur teenagers, finding jobs became difficult,” Shirmehmet told Religion News Service, the Islamic call to prayer echoing behind him. “Even driver’s license is very difficult to get for Uighur people. The passport, even more difficult.”

After the events, Thum noted, Urumqi also saw “incredible levels” of both militarization and ethnic animosity, with security forces and cameras at every corner as well as boycotts between Uighur and Han businesses. Uighur acts of “violent resistance” saw a spike as a result of the conflict, too, he said.

“The events of July 5, 2009, and afterward made China’s government realize that the stick-and-carrot policy is not effective,” said Nury Turkel, a Uighur lawyer who was recently appointed to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. “So they give up on the carrot, and they focus on the stick.”

But even as the crackdown against Uighurs in the region has accelerated, for some Uighur activists, the 2009 uprising remains a hopeful reminder of Uighur unity in the face of intensifying state suppression.

“Always, Chinese wanted to assimilate Uighur culture and Uighur identity into a Chinese culture and identity,” Shirmehmet said. “This is also one of the reasons for the concentration camps today. They want to brainwash us, indoctrinate us. But it is not going to work. … Our pride and our identity is in our blood.”