(RNS) — Remote learning will be the rule for schoolchildren in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for at least nine weeks this fall as the city tries to stem a surging coronavirus caseload.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll all be staying home.

Some could be in church instead.

That’s the vision at St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church, one of several churches in Winston-Salem hoping to host remote-learning sites for small groups of socially distanced kids.

If the bishop approves the idea, as many as 30 students would gather daily — spread across three buildings at St. Timothy’s campus — in the mornings.

Church volunteers would enforce health protocols, tutor and lead prayers to begin and end the day.

“We know in our faith that it’s not good for us to be alone,” said St. Timothy’s Rector, the Rev. Steven Rice, in a reference to the Bible’s Book of Genesis. “Some socialization among people of their own age will be a great benefit (to the students). And if both parents have to work, at least half the day is better than nothing.”

From Connecticut to Hawaii, congregations are seeking ways to support families still smarting from last spring’s sudden adjustment to home-based learning during the pandemic lockdown. They’re exploring how underutilized church buildings might be put to a new use that allows education to continue while freeing up parents to work and attend to other responsibilities.

Proposals range from hosting students during online classes to providing study hall space for them to work independently.

In such efforts, youth ministry experts see a promising opportunity.

“This is a way of reimagining children’s and youth ministry during a pandemic in a really amazing way that serves families and meets concrete needs,” said Angela Gorrell, assistant professor of practical theology at Baylor University and author of “Always On: Practicing Faith in a New Media Landscape.” “You can connect with kids in your neighborhood who might not otherwise be a part of your children’s and youth ministry.”

Congregations hope these plans can help reduce the acute stress they sense in their communities, especially among parents who can’t easily pivot to work from home and supervise children all at once.

In some cases, longstanding partnerships with districts are bearing new fruit.

Consider rural Graham County, North Carolina, where 8,500 people reside amid the Great Smoky Mountains. Locals depend largely on tourism jobs, such as cleaning second homes owned by residents of Atlanta and Charlotte. When the pandemic hit, 16 churches — Dry Creek Baptist, Eternal Believers and 14 others — became sites where families every day could pick up school lunches to go, along with breakfast for the next morning.

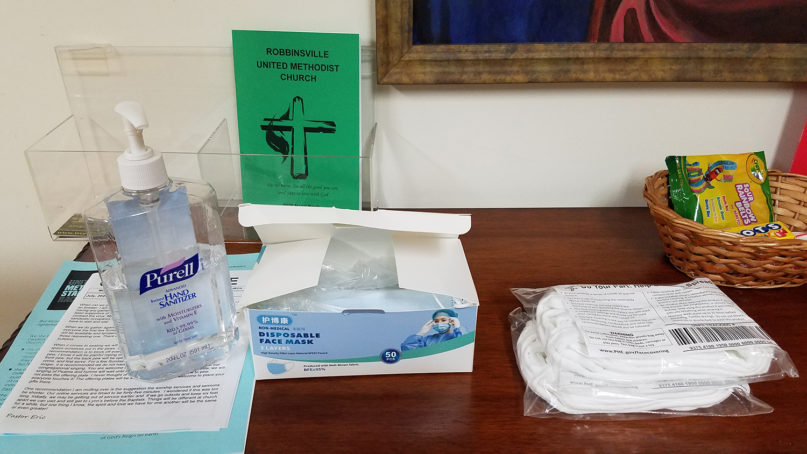

Supplies including masks and hand sanitizer are laid out for visitors on July 21 at Robbinsville United Methodist Church. Photo courtesy of Eric Reece

At least six Graham County churches also received mobile hotspot devices from the district, said Pastor Eric Reece of Robbinsville United Methodist Church, which received one of the devices.

That made them oases in what Reece calls an “internet desert,” where connectivity in homes is unreliable or unavailable. Robbinsville students were able to get their assignments and complete online coursework at his church when they picked up lunch.

Now Robbinsville UMC is gearing up to offer 40 hours a week of drop-in study hall access this fall. With Graham County schools operating at reduced capacity and having kids learn virtually on select days, students will be able to drop by the church with a parent any time between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., log on and work in the fellowship hall. Two adults from the church will be there to supervise.

To respect social distancing, no more than 10 children will be allowed at a time.

“On their day that’s virtual, if they don’t have Wi-Fi at home, they can come here,” Reece said. “They can use their (district-issued) Chromebooks to go online and stay caught up on their work.”

In New Haven, Connecticut, the Greater New Haven Clergy Association announced this month (July) that as many as 15 congregations are prepared to host children on days when they’re expected to learn virtually, which will be one to three days per week, depending on grade level.

Remote sites are needed, clergy say, because New Haven schools found that thousands of students were not engaging in school virtually from home. Among the reasons: no internet at home or no parental oversight of the learning process.

What role New Haven churches will have, if any, remains to be seen.

Among the topics of discussion: Will school buses bring kids to and from churches? Will schools send staffers to supervise remote learning or leave supervision to church volunteers? Will churches lease space to the district for remote learning or offer space free as a ministry to families?

“I’m not looking for any money to do this. I just see a need, and I don’t want money to be a hindrance to why we can’t get it done,” said the Rev. Steven Cousin, pastor of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in New Haven.

If technology supports are needed, Cousin said churches might seek in-kind donations from corporate sponsors.

The Rev. Boise Kimber, pastor of First Calvary Baptist Church in New Haven, said that if churches provide a service to schools, they might deserve compensation.

“We have to have that conversation with the district and see what they’re willing to do if we take care of this for them,” Kimber said.

In some cases, churches and schools can build on past cooperation.

One of the areas that Voyager Public Charter School will rent from Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in Honolulu for the upcoming school year. Photo courtesy of Evan Anderson

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in Honolulu has rented out space in its former elementary school to nearby Voyager Public Charter School for almost a decade. The church also temporarily housed another school when that one suffered a flood.

Now Voyager urgently needs extra space in order to reduce density by spreading students out across a larger campus footprint. Our Redeemer’s solution: For a nominal fee, the church will provide an extra 8,000 square feet for a year in what used to be its high school building.

“The ‘annexed’ space makes it possible to spread our elementary grades out on our main campus to accommodate all-day, everyday face-to-face instruction for our K-2 learners, and 2 days/week for grades 3 through 6,” said Voyager Principal Evan Anderson in an email.

There are some challenges to hosting students in churches, from extra sanitation requirements to liability concerns, but optimists believe those can be managed by following guidelines from governments, denominations and insurers.

Still, some faith leaders regard it as too risky for their congregations to undertake.

“It’s a huge issue: People can’t bring their kids to work, and many don’t have the sort of jobs where they can work from home,” said the Rev. John Cager, president of the Los Angeles Council of Religious Leaders and pastor of Ward African Methodist Episcopal Church. “But there are few states as litigious as California. You bring the kids in and even if the district provides the supervision, what’s the church’s exposure if someone’s kid gets sick? … Everyone wants to do ministry, but no one wants to get sued doing ministry.”

In locations where churches feel able to help, districts are expressing gratitude.

“Not every family has a strong safety net of support for children, so we are leaning on our community partners of all kinds to help us create multiple safe places and spaces where children can learn and access their lessons,” said Brent Campbell, spokesperson for the Winston-Salem and Forsyth County Schools in an email. “Faith-based partners and others are offering to open their doors.”