(RNS) — Many might assume the feminists who fought for women’s right to vote were casting off the shackles of religion.

There were certainly some of those. But many suffragists who pushed for the 19th Amendment, ratified 100 years ago today (Aug. 18), had a complex relationship with faith.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the first leaders of the movement, famously wrote of the Christian Bible, “I know no other books that so fully teach the subjection and degradation of woman.”

In 1895, she published “The Woman’s Bible,” in which she and a committee of 26 other women challenged the biblical interpretation of the first five books of the Bible as being biased against women.

Stanton, like some of the suffragists, was a freethinker who did not attend church and saw Christianity as hostile to women’s rights.

But as the group grew and coalesced, it also included women of many faiths.

Here are five of them:

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898): Christianity adversary

Born into a Baptist family, Gage collaborated with Stanton, the more famous of the suffragists. Discouraged with the slow pace of suffrage efforts in the 1880s, Gage turned her attention to the role of Christianity, which she perceived as devaluing women. In her 1893 book, “Woman, Church, and State,” she argued that the foundation of women’s oppression is in Christianity, particularly the story of Eve’s temptation in the Garden of Eden. Her view was that if there were no sin of Eve, there would be no need for a redeemer, said Sally Roesch Wagner, a historian who is also executive director of The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation Inc. Gage became fascinated with Native American societies, especially the Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois), where women were allowed to vote and own property.

Frances Willard (1839-1898): Christian nationalist

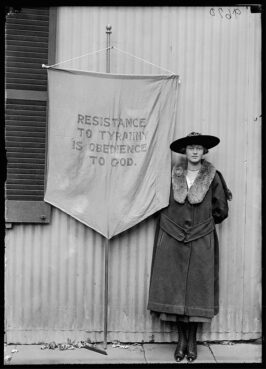

A suffrage supporter poses with a banner, circa 1917. Photo by Harris & Ewing/LOC/Creative Commons

Willard was perhaps best known as the founder of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and a leader in the Prohibition movement. But beginning in the 1890s, she became a suffragist and took her mighty group of Prohibitionist women along with her. Willard also believed in making the United States a Christian nation and tearing down the separation of church and state. She said she wanted to “recognize Christ as the great world-force for righteousness and purity, and enthrone him as King.” Gage called Willard “the most dangerous woman in America.”

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883): Anti-slavery feminist

A former slave, Truth was a member of the founding congregation of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and was known for preaching against slavery. She was also an early advocate for women’s suffrage and led the way for thousands of other Black women to join the movement. Truth tried to cast a ballot for Ulysses S. Grant in the 1872 presidential election and was refused. She inspired Black suffragists, even though many Black women, especially in the South, were not allowed to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Black churches, said historian Susan Ware, provided “a supportive role for the activism of African American women in the wider suffragist movement.”

Emmeline Wells (1828-1921): Mormon suffragist

Wells was a journalist who wrote many articles about women’s rights for the Women’s Exponent, a periodical that published news about women for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Women in Utah were able to vote for a short time before it became a state. When those rights were taken away, Mormon women became active in the national suffragist movement, with the support of the church. For many like Wells, the right to vote fit neatly with the right to plural marriage or polygamy. Wells later became president of the church’s Relief Society, the church’s welfare and relief organization. Unlike many of the founding suffragists, she lived to see the ratification of the 19th Amendment, dying the following year at 93.

Ernestine Rose (1810-1892): An early Jewish rebel

She has been called the first Jewish feminist. But the Polish-born Rose, who was an abolitionist in addition to being a suffragist, also rejected God. Unlike some of the freethinkers in the movement, who were critical of Christianity but did not deny belief in God, Rose was an atheist. Despite this, she was elected president of the National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1854 and lobbied to allow married women in New York state to retain their own property and have equal guardianship of children. Susan B. Anthony, perhaps the foremost leader of the suffragist movement, considered Rose a pioneer in the cause of women’s suffrage.

(National reporter Adelle M. Banks contributed to this report.)