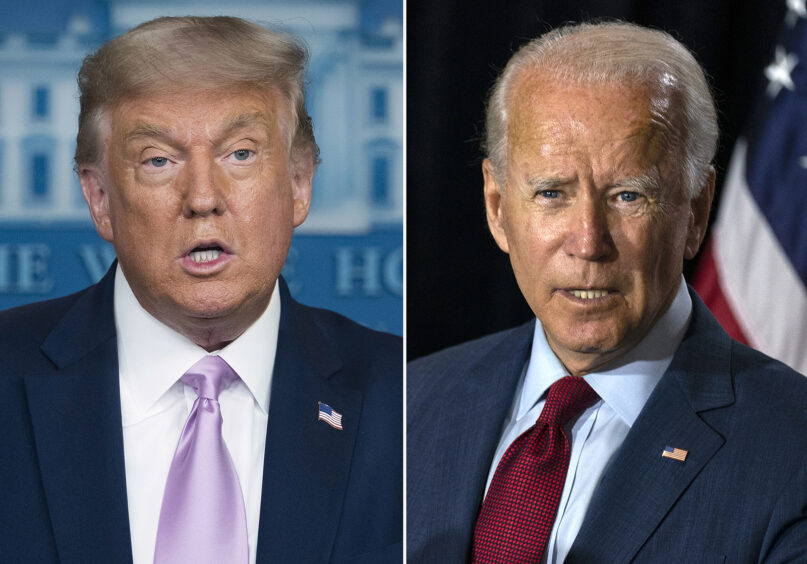

(RNS) — After the Democratic convention last week, the party line from Trump’s people was: Sure, anyone can read a teleprompter.

It’s an odd critique to choose, especially when your candidate regularly flubs his teleprompter lines (revealing, for instance, that he thinks Thailand is pronounced thigh-land).

But this criticism is effective because, to its intended audience — particularly evangelical Christians — it paints Biden as rehearsed, academic and, most of all, inauthentic. It implies that he’s not speaking from the heart.

The Republican Party wants to claim that Trump is the authenticity candidate — the one who will tell it like it is regardless of what people want to hear — because of the appeal that has to evangelicals. The idea that spontaneous, emotional reaction is more authentic than what is rehearsed sits at the heart of the evangelical spiritual tradition; it dates back to the theological conflicts of the 1600s.

For hundreds of years prior, Christians had practiced their faith through ritual and liturgy. The pageantry and ceremony of church celebrations and the liturgical calendar were the seasons of life for Christians. But in the 16th century, reformers sought to purify the Church of England of all this pomp and circumstance, performance and liturgy.

Reformers rejected rituals and liturgical prayer as harmful to the spiritual lives of Christians because they believed such acts encouraged inauthenticity. Ceremonies and rituals were compromised, they argued — bound up with Catholic superstition as much as with Christian doctrine.

Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden speaks during the fourth day of the Democratic National Convention, Aug. 20, 2020, at the Chase Center in Wilmington, Delaware. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Liturgy, the reformers said, was repetitive, dull and an invitation to “perform hypocritically,” in historian Lori Branch’s phrase, making it all too easy for churchgoers to speak words that didn’t reflect the true emotions of their hearts.

These debates were not minor events in cloistered hallways, affecting only a few; they led to civil war. And though the radical reformers eventually lost control of England’s national church, they didn’t fade away.

A small group of English Protestants remained convinced that liturgical prayer was wrongheaded. The only true prayer, they said, was spontaneous, free prayer. For that reason, among others, more than 2,000 ministers left the pulpits of the Church of England, never to return.

Some of these Puritan nonconformists left for New England, where they eventually formed Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, and Congregationalist churches (most American evangelical congregations can trace their heritage back to these reformers). They brought with them a conception and practice of prayer that indexed authenticity to spontaneity.

John Bunyan, known today as the author of “Pilgrim’s Progress,” was one such free-prayer advocate. His fear of insincerity was so great that he instructed his readers not to pray the Lord’s Prayer or to teach it to their children lest they speak its words without really meaning them.

Instead, he — and others — advocated the spontaneous pouring out of the heart in prayer. That kind of prayer, they said, was evidence of a converted heart and a sincere faith.

Is it any surprise that evangelicals tutored in the belief that spontaneous prayer is authentic prayer now see spontaneous political speech as authentic, too? This valuing of emotional outburst over practiced phrases is part of why evangelicals — the direct descendants of these reformers — fall for Trump’s schtick. They believe an appearance of being spontaneous, of speaking off the cuff, equals authenticity.

Trump is a “straight-shooter,” someone who refuses to play the D.C. game, someone who isn’t afraid to hurt people’s feelings by “telling it like it is.”

President Donald Trump speaks during the first day of the Republican National Convention, Monday, Aug. 24, 2020, in Charlotte, North Carolina. (AP Photo/Chris Carlson)

In 2015, a huge majority of GOP primary voters, 76%, told pollsters they believed Trump “says what he believes,” rather than saying “what people want to hear.” And this is still what we are asked to believe; at the RNC convention, Ivanka Trump praised her father’s authenticity, saying, “Dad, people attack you for being unconventional, but I love you for being real.”

But after four years of Trump’s version of authenticity, it’s past time to ask if being spontaneous and “true to yourself” ought to be high values.

If your self is deeply flawed, selfish and narcissistic, then being true to it is not a virtue at all.

I don’t particularly want a political leader who is true to himself; I want a leader who is trying to be true to the best ideals of our nation. If a leader’s authenticity just means he is mean, nasty, hateful, narcissistic and selfish, I can’t see that such authenticity is something to admire.

To be authentic is not to tap some inner well of individuality and spew emotion from there; to be authentic is to practice playing the role you’ve been given, as we Christians do when we recite creeds and the Lord’s Prayer, and as our political leaders can do when they study policy and history and ethics and listen to advice from a wide range of wise counselors.

The Republican Party, in choosing not to publish a policy platform at their own convention this week, but simply to pledge allegiance to Trump, has signaled their preference to follow the whims of an authoritarian demagogue rather than to strive to uphold a set of ideals or policy goals.

They have declared their freedom from any external moral script.

So this year, let the authenticity candidate be the one who’s reading a teleprompter. It may be that neither of these candidates is truly good. But I believe one is trying to be.

This year, I’ll take the guy reading words of hope and justice from a teleprompter over the guy spontaneously spewing fear and prejudice while he falsely claims to be telling it like it is.

(Amy Peterson is a writer, teacher and postulant for ordination in the Episcopal Church. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Image, Christianity Today, The Millions, Christian Century, and elsewhere. She is the author of “Where Goodness Still Grows” (Thomas Nelson, 2020) and “Dangerous Territory: My Misguided Quest to Save the World.” Follow her @amylpeterson. The views in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)