VATICAN CITY (RNS) — In his new book, “Church, Interrupted: Havoc & Hope: The Tender Revolt of Pope Francis,” papal historian John Cornwell forecasts the repercussions Pope Francis may have for the Catholic Church, portraying Francis as a priest, bishop and pope who has never been afraid of paving his own way.

“I have focused on a consistent feature of his papacy: a capacity to hold opposites in tension, his many paradoxes giving rise to disruption,” Cornwell writes.

A veteran writer on Catholic affairs, Cornwell is very much aware of the profound challenges facing the church today. Priestly vocations are dropping, pews remain empty and the sexual abuse and financial scandals in the Vatican have seeded doubt in the institution.

Francis emerges in Cornwell’s book as a figure capable of addressing the contradictions and polarization in Catholicism today, not through doctrinal imperatives but through the dictates of mercy. This quality renders him capable of adapting the Catholic faith to the practical demands placed on it today.

Francis’ unwillingness to favor either side in the culture battles splitting the Catholic Church has earned the pope skeptics and outright enemies, liberal and conservative. But Cornwell spies a glimmer of hope beyond the vitriol of Catholic Twitter, a new zeal that inspires everyone from Latin Mass enthusiasts to the faithful religious and lay groups helping migrants at European and American borders.

“Church, Interrupted: Havoc & Hope: The Tender Revolt of Pope Francis” by John Cornwell. Courtesy image

“Through all the disruptions, upheavals, and antagonisms, I have detected a sense of renewed spiritual energy among Catholics, whatever their standpoint within the Church, an energy that burns brightly beyond the politics of division,” Cornwell writes.

Cornwell made his reputation as an astute Vatican analyst with his 1989 book, “A Thief in the Night,” in which he challenged conspiracy theories that Pope John Paul I, who died after only 33 days as pontiff, was poisoned by his enemies within the Vatican.

In 2000, his controversial “Hitler’s Pope” took up the long-debated question of what role Pope Pius XII had in Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and beyond. Cornwell’s book gave a damning account of the pope’s behavior, which remains a highly contested topic among Catholics today.

Cornwell also wrote on Francis’ predecessor, the now St. Pope John Paul II, in his 2004 book “Pontiff in Winter.” By his own admission, the author presented a less than glowing review of the popular pope that led him to “become something of an outsider as a Catholic writer.”

Undaunted, Cornwell has focused on another controversial pontiff, in whom he sees “the possibility of new beginnings, a promise of hope, for the entire Church— practicing, lapsing and lapsed.”

Each of the seven parts of “Church, Interrupted” addresses a specific sphere of Francis’ story, theology or approach. The common thread is the “disruptive innovation” of this pontificate, a term taken from internet entrepreneurs referring to new products or services — think Uber — that completely change the existing market.

Francis was challenged from the very beginning by the existence of Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI, who, though retired since 2013, continues to wear white, live inside the Vatican and stand as a mostly unwilling champion for Francis’ doubters. Cornwell identifies “the inherent dangers of two living popes, or rather a living pope and an active ‘undead’ one, living side by side.”

Cornwell doesn’t buy into the “cozy two popes” story promulgated by Vatican media but states that for Francis, “Benedict became his shadow, the undead pope emeritus. His very existence encouraged critics who sought to undermine Francis.”

RELATED: Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI shuts down ‘fanatics,’ saying Francis is the only pope

The central chapters of the book recount the flurry of criticism thrown at Francis in 2018 — the “Annus Horribilis,” as Cornwell puts it — when the pope was besieged by attacks from liberals and conservatives alike and the legitimacy of his pontificate was challenged.

That year, Francis dismissed accusations against a Chilean bishop accused of covering up clerical sexual abuse as “calumny” but later had to backtrack and apologize. In August, he grappled with a disenchanted crowd of Irish Catholics gathered in Cork, Ireland, for World Family Day, after a letter intended to make amends for clericalism and sexual abuse by the country’s clergy was ill-received.

That same month, a former Vatican envoy to the U.S., Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, accused Francis of covering up abuse allegations against ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick.

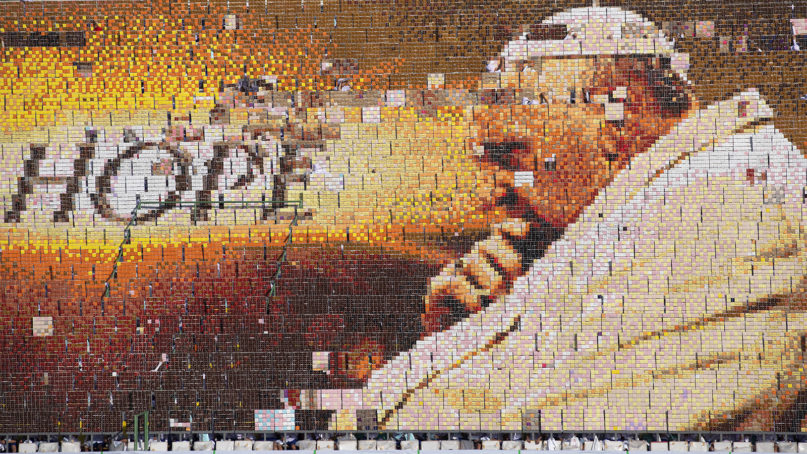

In this Sept. 23, 2015, file photo, Pope Francis reaches out to hug Cardinal Archbishop emeritus Theodore McCarrick after the Midday Prayer of the Divine with more than 300 U.S. bishops at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington. (Jonathan Newton / The Washington Post via AP, File)

“To question this pope’s authority would legitimize questioning any other pope’s authority,” Cornwell writes, musing that “Perhaps the disruptive questioning of papal authority was precisely what Francis intended.”

Yet it is amid chaos and division, Cornwell said, that the disruptive quality of this pope comes out. When Francis apologized for his misgivings in Chile, he did the “unthinkable,” the author writes. “It may take some years and several papacies more for it to sink in; but the papacy could never be the same again,” he added.

Cornwell sees innovation as well in Francis’ efforts to decentralize the church, be it by reforming the Vatican’s tangled media apparatus or encouraging clergy to address the pastoral needs of divorced and remarried couples.

Writing about the pope’s encyclical on the care of creation, “Laudato Si’,” and his apostolic exhortation “Querida Amazonia,” Cornwell delivers his most eloquent chapters, detailing the importance of the pope’s environmental message and its profound impact on humanity as a whole.

In the media battle between liberals and conservatives, Francis represents “a third way,” the author writes, “an audacious prudence, which keeps the apparent opposites, with their accompanying rewards and dangers, in tension.”

The book goes so far as to compare Francis to Pope Gregory I, the sixth-century pontiff known as “The Great.” Yet, Cornwell nimbly avoids getting caught in the left-right debates by offering a holistic grasp of Francis and expressively capturing his profound, but often overlooked, nuances.

Cornwell believes that the widely discussed, and misunderstood, “Francis effect” has injected a new vitality into a dormant Catholic community, which “is often obscured by the media clash of liberals and conservatives.”

“While there has been talk of schism during the papacy of Francis,” he continues, “the vibrant associations of Catholics show that what Catholic groups hold in common is stronger than their differences, even when those differences grow strident.”

RELATED: How Catholicism became a breeding ground for conspiracy theories