(RNS) — Passover is Michael W. Twitty’s favorite Jewish holiday.

A cook and award-winning culinary historian, Twitty owns that food is a big reason for his love of Passover. But that’s not all. According to Twitty family lore, the holiday, on which Jews retell their exodus from slavery to freedom, also coincides with Twitty’s enslaved ancestors effectively watching the end of their own bondage in the American South.

The way Twitty tells it, his great-great-grandfather, then 15 and born into slavery in Appomattox County, Virginia, happened to be standing outside the courthouse when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his troops to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, ending the Civil War and within days freeing slaves across the South.

The date of the surrender, April 9, 1865, fell one day before the start of Passover that year.

“Think of that symbolism,” said Twitty, who converted to Judaism when he was 25. “I’m a part of Jewish civilization. My great-great-grandfather’s family had been enslaved for 150 to 200 years. The fact that he was able to see the end of the Confederacy, the end of enslavement and the beginning of us being a free people, if not on the eve of it, is quite powerful and not coincidental.”

READ: This Passover, kosher pig’s on the menu

Twitty’s enslaved ancestors were not Jewish. Nor were his parents. His mother attended a Black Lutheran church; his father was Baptist. But his family’s experience of emancipation connects him to the Jewish Passover tradition.

“There are many different kinds of enslavements and people experience them differently,” Twitty said. “But there’s power in talking about enslavement from the viewpoint of freedom.”

This past year, in which so much attention has been given to the killings of African Americans at the hands of police, has been a painful one for Black Americans. Black Jews, a minority within a minority, have suffered in particular, as the white Jewish population struggles to come to terms with the ways they have benefited from white power structures and often shut out Jews of color.

Twitty has encountered his fellow Jews’ reactions on social media, where his posts are often scrutinized by white Jews who question his Jewishness. Having spent 10 years teaching Hebrew school at Reform and Conservative synagogues, he finds the retorts galling.

His latest book in progress, “Kosher Soul,” will focus on Jewish and Black food traditions through the eyes of Black Jews and Southerners who converted to Judaism, including his own. (@koshersoul is also Twitty’s Twitter handle.) Its core message is that multiple identities can and should interact. In fact, it’s inevitable.

Through this interaction, the inequities of American life are leveled in a particularly American way. In his cooking, Twitty likes to advance what he calls culinary justice, an idea spun off from its better-known cousin, food justice. He wants people who are marginalized to lift up their humble foodways to enjoy a recognition equal to those of better-known and better regarded traditions.

“America is the one space where I’m possible,” he said. “That’s not a statement of American exceptionalism. That’s the fact that the intersections and crossroads that would make it possible for someone who is openly gay, Black and Jewish and of Southern heritage to represent himself really only happens here.”

In his first book, “The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South,” which won the 2018 James Beard Book of the Year award, Twitty chronicled his travels through the South, searching to understand his own personal history, including his mother’s Alabama roots, through food. For years, he has given living-history cooking demonstrations, dressed in period attire and cooking over an open fire using 18th-century tools.

On a Zoom talk this week hosted by the Jewish campus organization Hillel, Twitty encouraged Jewish college students and especially Black or mixed-race Jews to embrace their various heritages.

“I want people to understand that tradition is what you make,” said Twitty, wearing an ornamental yarmulke. “We are all these additions to a tradition which depends on morphing. You can’t be Jewish without morphing. There’s center, but it’s also spinning like a dreidel, making revolutions and creating new space and a new world.”

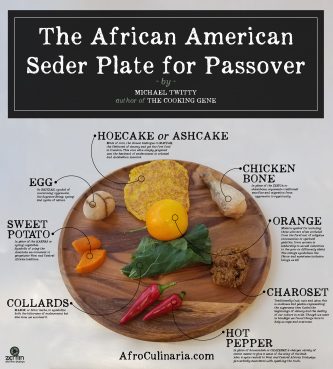

Michael Twitty’s seder plate includes a variety of ingredients, with chicken bones to sweet potatoes all holding symbolic value. Courtesy of Benjamin Jancewicz/Zerflin

His Passover Seder plate is a nod to that metamorphosis. Twitty has reinterpreted this symbolic plate, which traditionally sits at the center of the Seder table, with his own Black history. Instead of matzo, he has hoecake or ashcake — a thin, round flatbread made of corn that enslaved people used to eat. He used a sweet potato, a staple of the American South instead of a spring vegetable, and a hot red pepper instead of bitter herbs (typically horseradish).

This year’s Seder, shared only with his husband, Taylor Keith, at their home in the Maryland suburbs, will be modest: Twitty hasn’t yet been vaccinated for COVID-19. The menu is still evolving but will likely include matzo ball gumbo, matzo-meal fried chicken and potatoes with the Middle Eastern spice mix baharat, a recipe he picked up from a new cookbook from Jake Cohen, called “Jew-ish.”

On his call with Jewish college students this week, he urged them to remain true to who they are and to celebrate their braided traditions.

“We need to remind people of both the historical truth but also the absolute joy we take in celebrating who we are and keeping the memories of people who brought us here alive and giving something to our children in perpetuity.”

One way to do that, he believes, is through cooking: “Food is how we say we belong.”

READ: The swastika and the 4 H’s