(RNS) — For Juhem Navarro-Rivera, there’s a series of stages people like him go through when they leave behind their religious identities.

He refers to it as the three B’s.

“The behavior is the first thing to go. … You stop going to church or you stop praying,” Navarro-Rivera said.

Then, Navarro-Rivera said, it’s the sense of belonging, when “you stop identifying as whatever your family raised you.” Eventually, for some people, the belief starts to go away, Navarro-Rivera said.

RELATED: New report finds nonreligious people face stigma and discrimination

Navarro-Rivera, 42, grew up culturally Catholic in Puerto Rico. He was baptized, had his First Communion and graduated from a Catholic high school. He was also exposed to other Christian denominations through his Lutheran neighbor and by attending a Protestant elementary school. As he grew older, he became more interested in the separation of church and state. He also didn’t feel comfortable with the authority of priests. Plus, he said, he never truly practiced Catholicism. He just went through the motions of it.

Now, Navarro-Rivera, who is nonreligious, identifies as a humanist. As defined by the American Humanist Association, humanists are nontheists who believe in ethical values informed by science and their desire to meet people’s needs and affirm their dignity. And as the co-chair of the Latinx Humanist Alliance, an affiliate of the AHA, Navarro-Rivera is working to amplify the voices of Latinos who are nonreligious.

Juhem Navarro-Rivera. Courtesy photo

The number of nonreligious Latinos in the U.S. has increased 67%, doubling from about 4 million to more than 8 million Americans (also in part due to an increase in the size of the Latino population during the decade between studies), the Latinx Humanist Alliance found.

Now 1 in 5 Latino Americans have no religion, according to the Latinx Humanist Alliance.

These findings come from data that Navarro-Rivera, a researcher, analyzed from a number of sources, including the Public Religion Research Institute and the Pew Research Center.

For nonreligious people, there are a range of identities, from atheist and secular to humanist and skeptic. Through its 1 in 5 campaign, the Latinx Humanist Alliance hopes to amplify this growing group and let nonreligious Latinos know there is a community in humanism they can be a part of.

In humanism, Navarro-Rivera said, there’s an element of social justice. As part of their values, humanists are committed to diversity and “work to uphold the equal enjoyment of human rights and civil liberties in an open, secular society.”

“The focus of humanism is more into building coalitions with other groups, whether they’re believers or nonbelievers if our values align,” Navarro-Rivera said.

RELATED: Black skeptics find meaning in uplifting their community through social justice

In its analysis, the Latinx Humanist Alliance also found many nonreligious Latinos are young and come from Christian households, largely Catholic.

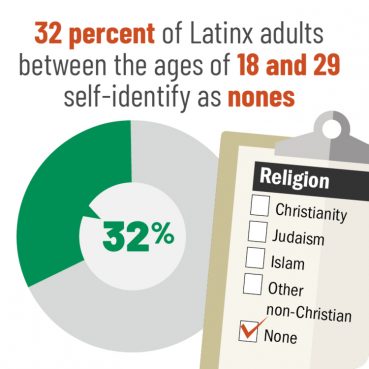

The Latinx Humanist Alliance found 32% of Latino adults between the ages of 18 and 29 identity as “nones,” meaning they are religiously unaffiliated. That same age group makes up only about 20% of the Latino Catholic community, according to the Latinx Humanist Alliance.

Graphic courtesy of Latinx Humanist Alliance

A large bulk of nonreligious Latinos were raised Catholic (57%) or Protestant (22%), while 14% grew up in nonreligious families, the Latinx Humanist Alliance found.

Arlene Ríos, who grew up culturally Catholic, grappled with identifying as an atheist later in life. She felt it carried a negative connotation. The word “atheist” just felt too ugly, she said.

As she explored nonreligious labels, she realized the importance of making it clear she didn’t believe in God, but she believed in the humanity of people. That’s why Ríos, who in January became the vice president of the Los Angeles-based Atheists United, has identified as an atheist humanist — although, she said, her identity continues to evolve.

A Navy veteran, Ríos also organizes meetups with other nonreligious Latinos in Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley. She said many people assume “everybody is a believer, especially in the Latino community.”

“There are a lot of Latinos out there who identify as Catholic but they don’t really follow the religion, or aren’t too involved in it,” Ríos said. “It’s kind of like something that they’ve inherited. … It’s part of the culture.

“I think the more Latinos who are nonbelievers that come out, the more it will be normalized,” Ríos said.

RELATED: American Humanist leader Roy Speckhardt stepping down to make room for diverse leaders

To Navarro-Rivera, this rise in nonreligious Latinos also has political and social implications.

Navarro-Rivera said there’s been too much focus on the growth of Latino evangelicals and around politically charged phrases like Latinos are a “community of faith” that embody “family values.”

During the last presidential election season, for example, then-President Donald Trump launched Evangelicals for Trump by visiting El Rey Jesús Global, a megachurch in Miami led by Latino pastor Guillermo Maldonado. Soon after, Joe Biden’s team launched Creyentes con Biden, which translates to Believers for Biden, to engage Latino voters from a faith perspective.

“When we talk about the religion composition of Latinos and the ‘Latino vote,’ it’s like this Catholic Protestant dichotomy,” Navarro-Rivera said.

And yet, he said, “nonreligious Latinos are driving a lot of the progressive attitudes you find in Latino public opinion.” Nonreligious Latinos, he said, are usually to the left of Latinos overall.

“It’s not that these groups are growing and they exist in large numbers. They’re also having an impact on Latino public opinion in general,” he said.