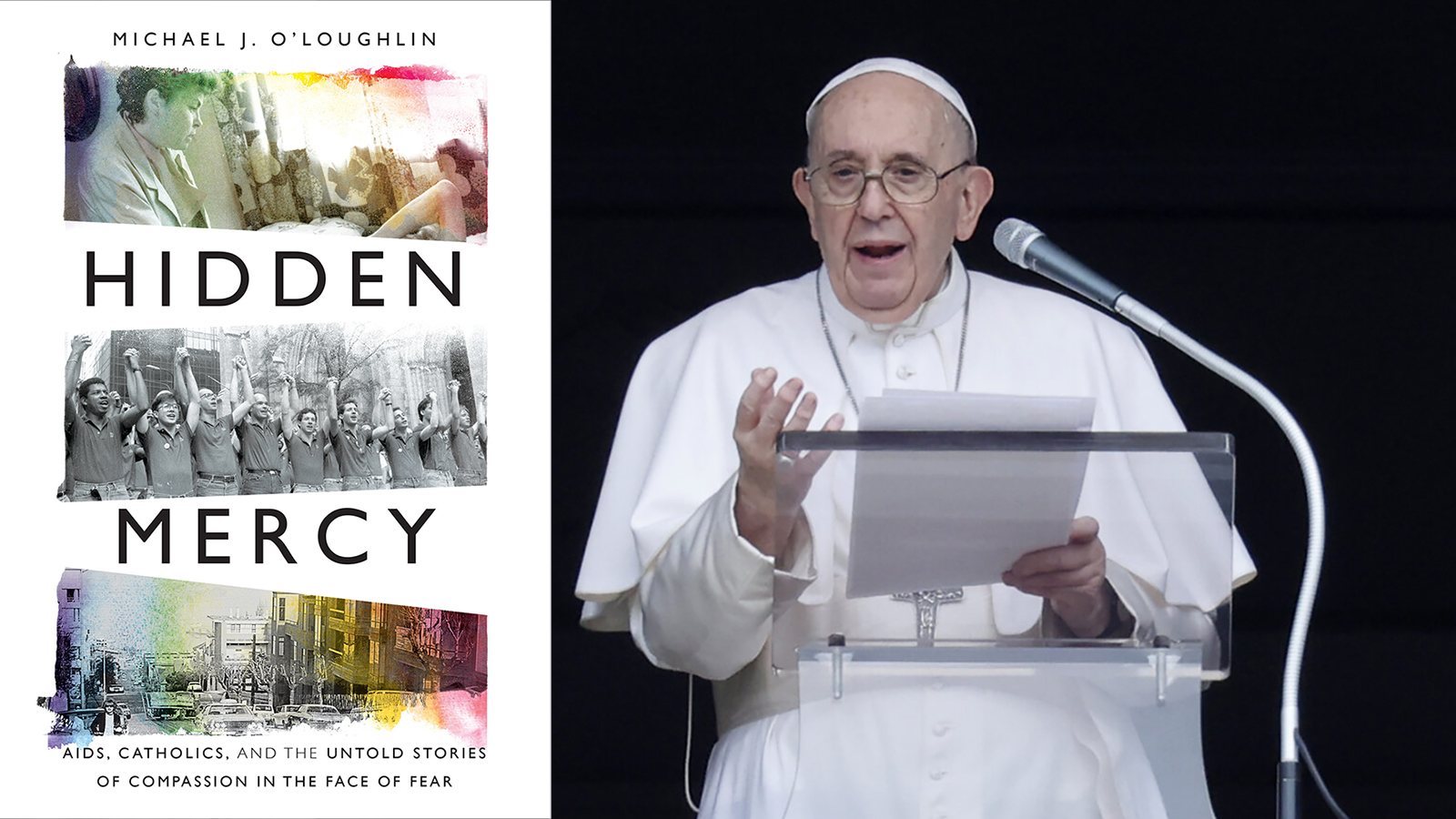

“Hidden Mercy” and Pope Francis. (Book jacket courtesy image; AP Photo/Riccardo De Luca)

VATICAN CITY (RNS) — In a letter to the author of a new book about the Catholic ministry to the LGBTQ community in the United States during the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, Pope Francis praised the ministry’s “discreet mercy,” despite stigma and opposition by the church.

The book “Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear,” written by journalist Michael O’Loughlin, addresses the reality of the LGBTQ community between 1982 and 1996 at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the United States and portrays the stories of Catholics who stood beside the community despite the discrimination they faced from society and the church.

The book releases Nov. 30.

Pope Francis said he was “spontaneously struck” upon receiving the letter and book by O’Loughlin “by that through which we will one day be judged: ‘For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me’ (Mt 25:35-36).”

In the letter, dated Aug. 17, Francis praised the book for “bearing witness to the many priests, religious sisters and lay people, who opted to accompany, support and help their brothers and sisters who were sick from HIV and AIDS at great risk to their profession and reputation.

“Instead of indifference, alienation and even condemnation, these people let themselves be moved by the mercy of the Father and allowed that to become their own life’s work; a discreet mercy, silent and hidden, but still capable of sustaining and restoring the life and history of each one of us,” the pope wrote.

When, in 2013, Pope Francis uttered the now-famous phrase “who am I to judge?” in response to a question about homosexual clergy, it sent shockwaves through the Catholic Church. Since then, the pope has met in private with LGBTQ individuals and supported their community though charitable works and in interviews.

Pope Francis has also upheld traditional Catholic teaching on marriage and family, rejecting gender theory as a form of ideological colonization. In March, the pope approved a document issued by the Vatican’s doctrine department banning the blessing of same-sex couples.

O’Loughlin spent the last three years gathering information and conducting hundreds of interviews on the little-known stories of Catholics who ministered to the LGBTQ community during the deadly AIDS pandemic in the United States. He profiled priests and nuns who spent their lives helping those affected.

Michael O’Loughlin. Courtesy photo

This “hidden ministry” occurred at a time when the Catholic Church — and society at large — “cracked down on homosexuality,” O’Loughlin said in an interview with Religion News Service. At the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, some Catholic prelates used incendiary language against homosexuals, while the Vatican issued letters defining same-sex relationships as “intrinsically disordered.”

The Conference of Bishops in the United States issued a document in 1987 on “The Many Faces of AIDS: A Gospel Response,” which urged faithful to provide pastoral care to those suffering due to the AIDS pandemic. It also condemned discrimination against people with AIDS as “unjust and immoral.” The document stood alongside traditional Catholic teaching opposing same-sex relationships, sex outside of marriage and the use of contraception.

“This really intense crackdown on the gay rights movement in the church is happening at a time when the community already feels under attack from society and is dealing with HIV and AIDS,” O’Loughlin said.

“Rather than bringing a pastoral response to this community in crisis, it seems to me they were cut off from the spiritual resources that could have been helpful,” he added.

As a result, O’Loughlin said, “an entire generation of LGBTQ Catholics really felt disconnected” from the church. The book addresses why LGBTQ Catholics chose to stay and examines the stories of the people, lay and religious, who convinced them to claim their place in the institution.

“The healing has taken decades, and I think it’s still an ongoing process,” he said.

RELATED: As Catholic bishops gather, so do protesters on right and left

An example of a priest supporting the struggling LGBTQ community during the AIDS pandemic is Father William Hart McNichols, who, through his ministry and artwork, “helped lessen the stigma” associated with AIDS, O’Loughlin said. Sr. Carol Baltosiewich became an advocate for the rights of the LGBTQ community in Belleville, Illinois, and moved to New York in 1986 to help those affected by HIV and AIDS. Through her ministry, Baltosiewich deepened “her own understanding of faith, and it actually made her a better Christian,” O’Loughlin said.

The author hopes these stories will encourage disaffected LGBTQ Catholics to “feel more empowered to take their place in the church.” Pope Francis’ pontificate, he said, has provided an opportunity for LGBTQ Catholics “to be more visible, to be more present, and there is a freedom to talk about these issues that didn’t exist over the past several decades.”

Pope Francis’ letter shows “he’s not afraid to engage with this history, no matter how difficult or taboo it might still be,” O’Loughlin said, adding that he hopes it will provide “some consolation and encouragement” to Catholics who felt like their work and ministry toward the LGBTQ community wasn’t recognized.

“Maybe it allows them to feel seen by the pope today,” he said.

RELATED: In praise of Archbishop Gómez’s anti-racism