Columns of non-Muslim refugees from West Punjab, Pakistan, moving toward India in September 1947. Photo by Photo Division, Govt. of India/Wikimedia/Creative Commons

(RNS) — In the early 1800s, my ancestors were one of the largest landholders in Punjab, having accumulated 42 feudal land grants called jagirs. “Batali” in Punjabi means 42, hence the village that lay on my family’s holdings were referred to as Butala, now a small village situated about 15 miles west of present-day Gujranwala, Pakistan. Our family name of “Butalia” thus became common.

Then came August 15, 1947, when Punjab was broken in two, with western Punjab becoming part of the new country of Pakistan and east Punjab remaining in India. Despite Mohandas K. Gandhi’s non-violent philosophy, the partition resulted in about 15 million people divided along religious identity lines crossing over to the other side. Half a million died in revenge killings as Sikhs and Hindus moved from Pakistan to India and Muslims moved from India to Pakistan. The carnage was equally horrific on both sides. My grandmother called it “the day we lost our humanity.”

When the partition of India and Pakistan looked as if it would become a reality, some of the family, including my dad and two of his brothers, moved from Butala village to Indian Punjab. But the local Muslims in our village had assured the family of safety, so my Sikh grandparents decided to stay put at the ancestral family home with their two younger boys. In September 1947, however, our ancestral house was set on fire by mobs from a neighboring village. The local Muslims saved the house and their lives.

But as weeks went by, local Muslims were now no longer able to protect the family that had lived in their village for generations. Finally, in late September, my grandparents decided to leave the village for Indian Punjab.

RELATED: Preserving stories of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh friendships through India’s partition

The day they were to depart, a young Muslim man whose grandparents had worked for the family stepped up and demanded that they not take anything with them except the clothes on their backs. It was at that moment my grandparents, Narinder Kaur and Capt. Ajit Singh (retired), realized that they were never to return to their home, their ancestral haveli that had a black peacock painted at the front entrance.

My grandfather wore a round turban similar to a Muslim man, my grandmother a burqa, holding their 3-month-old son Sarabjit Singh in her arms, put two-year-old Narinderjit Singh on a donkey and the Butalia family left the ancestral village on foot for good, never to return.

This story was repeated to me so many times by my aging grandma that I sometimes feel as if I was with them on this journey of hope and gratitude.

I eventually settled in Columbus, Ohio, where I teach engineering at Ohio State University. After several years, I began looking for my roots. With the help of Facebook, I slowly became friends with residents of Butala, back in Pakistan. One of them shared with me that my family’s onetime home was now an Islamic school for girls. I began to think about returning to the haveli someday and walk back through the door that my grandparents left in 1947 to complete the circle of life that left my grandma with such hope and gratitude that it overcame her suffering.

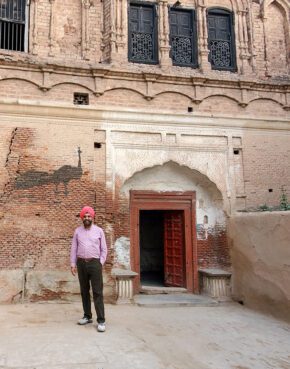

Tarunjit Singh Butalia visits his ancestral village in Butala, Pakistan, in Dec. 2019. Photo courtesy of Butalia

My opportunity came in December 2019, when I had reason to attend a conference in Lahore, Pakistan. I decided to visit our ancestral village.

As we drove toward the village from Gujranwala, my heart raced. I felt as if I knew the place, even though I had never been there before. When I reached our village with a mix of emotions of joy and sadness at the same time, I was perplexed — I was pointed to three havelis that had once belonged to my family. Then I saw on the front wall of one of the structures a fading black peacock made of black, burned bricks.

My heart melted and reminded me of my grandmother’s stories and her warm touch. Below the peacock were the doors out of which my grandparents had walked out more than seven decades before.

I was here to complete the circle of life, so with tears in my eyes and prayers on my lips, I kissed the threshold and entered the house, though, as it is a school for young women, men are not normally allowed in. The mullah of the village accompanied me inside and gave me a guided tour.

We all believe in stories, some good, some bad. We become the stories we believe in. My grandmother’s stories of the haveli were always filled with love of the place, despite the pain they had felt at leaving. I pledged, as I walked through the school, not to let the hate of the partition eclipse my love of humanity. Hate is a poison pill to the person who hates but does nothing to the object of hate.

RELATED: 75 years after India’s independence, a lost generation recovers its Hindu faith

Tarunjit Singh Butalia. Photo courtesy Religions for Peace USA

It took me much of my life to learn this lesson. If you believe in stories of hatred and revenge, that is who you will become. If you choose to believe in stories of love, forgiveness, compassion and humility — that is who you will develop into. So let us be careful what stories we believe in.

(Tarunjit Singh Butalia is executive director of Religions for Peace USA and a founding trustee of the Sikh Council for Interfaith Relations. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)