(RNS) — The Museum of the Bible marked its fifth anniversary last week. By all accounts, it has been a rocky ride.

Co-founded by Hobby Lobby President Steve Green using $500 million of his own fortune, the 430,000-square-foot building overlooking the U.S. Capitol has weathered a series of storms. Five Dead Sea Scroll fragments on display were found to be forgeries. A New Testament manuscript was determined to have been stolen. Federal authorities confiscated a rare Iraqi cuneiform tablet bearing a fragment of the “Epic of Gilgamesh.”

That’s just the artifacts. Early on, the museum conscripted respected biblical scholars to offer advice on the design of its exhibits. But many of them soured on the project, saying its messaging favored evangelical Christianity.

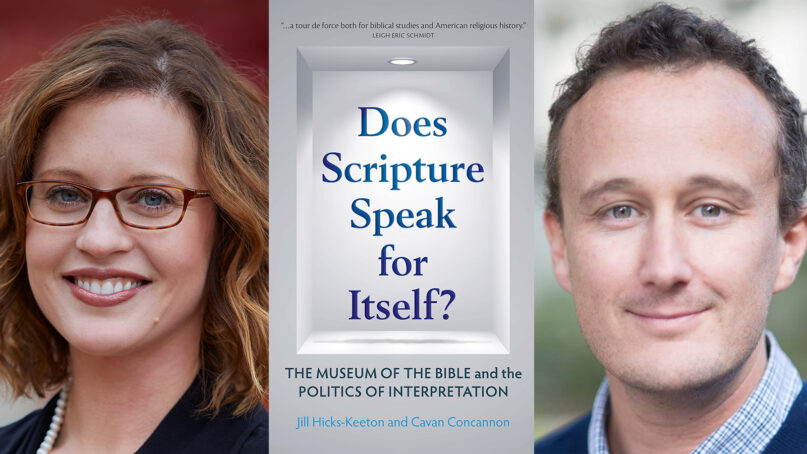

Now two scholars, Jill Hicks-Keeton, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, and Cavan Concannon, a professor at the University of Southern California, have teamed up for a second time to examine and explore the museum’s exhibits, theatrical experiences, publications, funding and partnerships. The book, “Does Scripture Speak for Itself?:The Museum of the Bible and the Politics of Interpretation,” argues that the museum is part of a larger 100-year-old project of white evangelical institution-building.

The museum, they say, attempts to bolster a white evangelical identity by producing a Bible that is benevolent, reliable and divinely inspired; a Bible that resists critique and has universal appeal.

The authors spent hours scrutinizing each floor of the museum, as well as numerous books written by Steve and Jackie Green, their daughter, Lauren, and son-in-law, Michael McAfee.

The Museum of the Bible entrance in 2017 in Washington. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

They conclude that the Greens — the latest in a long line of monied evangelical capitalists — have not just created a museum, but a kind of parachurch organization intended to hold up the Bible as central to American public life.

In a statement responding to questions from RNS, the museum said it disagreed with the book’s premise and claims. “We recognize that the Bible’s story is global and that its impact on different communities is historically varied and complex. As such, the museum strives to ensure our exhibitions are accurate and have historical nuance, which has been consistently confirmed by positive visitor feedback.”

RNS spoke to Hicks-Keeton and Concannon about their new book and how they believe it furthers the mission of white evangelicalism. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You’ve written about the Museum of the Bible before. Why this book?

HICKS-KEETON: The book represents a departure from our previous work. We’ve transitioned from seeing the museum as a conversation partner to an object of analysis. This book is the culmination of that thinking about what the museum is producing and how it influences politics in the U.S.

You argue that monied white evangelicals have built institutions to shape their theological identity. What are those?

Cavan Concannon. Courtesy photo

CONCANNON: We look at a number of different institution builders in the early part of the 20th century that played a role in forming the foundation of white evangelicalism today. Some of the people we mark are people like Lyman Stewart, a Western oil baron who paid for a number of different projects including Biola University as well as the publication “The Fundamentals,” which shaped a national identity for conservative Protestants. We also write about J. Howard Pew, a rabid opponent of the New Deal who began to fuse together a mix of libertarian economics and small-government conservatism with conservative Protestantism. We also pay attention to the building of radio networks, television networks and now things like podcasts. We pay attention to the building of Christian schools, Christian think tanks and Christian business networks. They’re all working together to amplify the same sets of themes. This museum is one of those institutions that has quickly integrated itself in the network.

You point out that the museum presents a white evangelical Bible. Why is the racial component important?

CONCANNON: Not all evangelicals are white. We’re talking about a sect shaped by whiteness. It’s less a demographic descriptor and more as a description of the institutional makeup. It’s a culture of whiteness. Some people in that orbit are not demographically white.

HICKS-KEETON: People think of white evangelicalism as an accusation. But we mean it as a description. We are not saying, ‘Hey look. They get the Bible wrong.’ Instead we’re pointing to the museum as an institution founded and funded within white evangelicalism and then asking, ‘What is the Bible they are producing?’

CONCANNON: If someone is offended by the idea that we say this is a white evangelical Bible or a white evangelical institution, that means they’re associating the phrase with being racist. That says more about their anxiety than the term itself.

You write that the 2019 exhibit on the Slave Bible, which shows how Americans carved up the Bible to justify slavery, ends up absolving the Bible. Explain why you don’t think that’s so.

Jill Hicks-Keeton. Photo by Travis Caperton

HICKS-KEETON: Everyone looks back and decries slavery as an ethical wrong. And yet historically, we can’t get around the fact that many white Christians were using their Bibles to endorse slavery and justify the enslavement of people. The PR campaign (around the exhibit) presented this as a reckoning with the idea that the Bible has been misused by people who did bad things. It rhetorically works to disentangle the Good Book from the bad deeds. It was less an exhibit that enabled people to interrogate how Bibles in the 19th century were used and deployed in thinking about enslavement and more about exculpating the Bible from complicity in that harm. One can imagine an exhibit that centered how enslaved and formerly enslaved Africans in the U.S. engaged with the Bible. That’s different from how white people were thinking and using the Bible. That’s something that the Slave Bible exhibit can’t get to because it’s centering an artifact produced by white people.

Many biblical scholars have been at war with the Museum of the Bible. You’re saying that fight is unproductive. Why?

CONCANNON: One of the things we came to understand was that we were gatekeeping access to who gets to say what about the history of the Bible — the museum and its monied interests or biblical scholars. Our own field of biblical studies has its own problematic history of being shaped by whiteness and European colonial interests. We felt less interested in fighting for that project than analyzing how both groups — biblical studies and the Museum of the Bible — function and work. There is no one Bible out there that we can all figure out the meanings of. There are only various iterations of biblical literature. We wanted to analyze how people produce and make meaning out of those, rather than fighting for one or the other.

Would you want the museum to be renamed the White Evangelical Museum of the Bible?

CONCANNON: It’s not up to us to tell them what to do. We can and do want to interrogate what they mean when they say Museum of the Bible. What does that mean? It’s a claim to a universal definition of the Bible that we want to particularize.

HICKS-KEETON: While it’s not up to us, if they did change the name to the Museum of the White Evangelical Bible, I wouldn’t mind.

You say the museum’s history floor valorizes colonialism. How does it do that?

HICKS-KEETON: It wants to trace the path to universal access for the Bible. There’s a series of developing technologies that are highlighted, one of which is the Gutenberg Bible. We argue one of the technologies needed to get the Bible worldwide is European colonialism. It is celebrated in this narrative because it was the means by which the Bible spread across the world, according to the museum.

Do you think the museum promotes a Christian nationalist ideology?

CONCANNON: The museum is concerned with showing that the Bible is good for society. When people use it to do bad things, they’re misinterpreting it or abusing the Bible. What’s being promulgated is a Christian nationalist argument for putting a Bible at the center of public life.

HICKS-KEETON: The Museum of the Bible is normalizing a Bible that authorizes white evangelical dominion. If the Bible that the museum is producing were to become the Bible people see as authoritative, it would protect and increase their power in the country.

RELATED: As Trump launches new presidential bid, will former faith advisers back him?