On Purim, observant Jewish men, to varying degrees, imbibe strong drink. And Jewish women do their best to keep the men safe and anchored in civilization. The holiday thus may not seem very female-centered. But, in truth, it is.

Not just because its hero is a heroine and the holy book about the historical event it commemorates is named after her, but because the Book of Esther, or “Megillas Esther” (generally called “the Megillah”), verily revolves around femininity.

Achashverosh, the pliable, preposterous monarch we meet at the start of the narrative, is a poster child (or, perhaps better, poster adolescent) for male chauvinism. His 180-day drinking party, as the Talmud describes it, was a bacchanal of arrested-development “good ol’ boys” acting like louts. And it entailed the debasement, and eventual dispatching, of his queen, Vashti.

And the next action of the foolhardy king was to organize the antithesis of true respect for women: a beauty contest — a compelled one, yet.

Achashverosh, moreover, ends up being manipulated by a woman, our reticent, modest heroine Esther, and he is led by her to dispatch the Jews’ mortal enemy, Haman, saving her people from his evil plans.

But there’s even more here, too, and more subtle. Mordechai, Esther’s cousin, the ancient rabbis teach us, was miraculously able to physically nurse the baby Esther when she was orphaned. Thus the male hero of the Purim story is rendered, at least in a way, something of a heroine himself.

Surprising and sublime thoughts like those are lost, however, on many people, certainly those who imagine they are somehow taking a stand for womanhood by celebrating, of all people, Vashti.

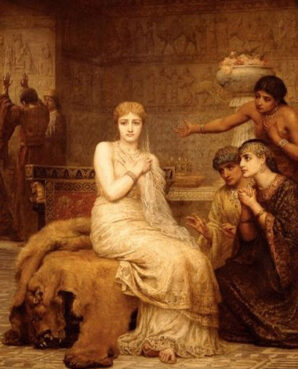

“Vashti Refuses the King’s Summons” by Edwin Long, 1879. Image courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons

According to Jewish tradition, Vashti enslaved, beat and humiliated Jewish women and forced them to do work for her on the Sabbath. Hardly the stuff of a feminist icon.

What seems to have endeared Vashti to some is her refusal to obey Achashverosh’s summons to flaunt her body to his male drinking partners. But that, according to the Talmud, was out of vanity, not feminist pride; her body betrayed her at that time, breaking out in something like severe acne (or, in one opinion, sprouting a tail).

Yet, one contemporary pundit declared: “Saving the Jewish people was important, but at the same time, (Esther’s) whole submissive, secretive way of being was the absolute archetype of 1950s womanhood. It repelled me. I thought, ‘Hey, what’s wrong with Vashti? She had dignity. She had self-respect.’”

Well, self-regard, anyway.

Another writer describes Vashti as “a brave woman who risked her life for her beliefs,” seeing the Megillah’s message as, “Women who are bold, direct, aggressive and disobedient are not acceptable; the praiseworthy women are those who are unassuming, quietly persistent …” and laments “the still-pervasive influence of the Esther-behavior model.”

And yet another advocate calls Vashti “a foremother in the best sense of the word — assertive, appropriate, courageous.”

Although it’s hardly the first time it has happened, it’s still sad to see a carefully preserved Jewish historical tradition sacrificed on the altar of a contemporary ism.

In their blind capitulation to the contemporary notion of feminism, the Vashti-embracers mangle the Megillah and mistake a malevolent oppressor for a role model. Sadder still, they entirely miss the genuinely feminist, if countercultural, example of Esther: that her true power came not in adopting the social trappings of masculinity like assertiveness, self-regard and obstinateness but in the embrace of traits often considered feminine, like modesty, selflessness, faith and courage.

It’s not a message that easily resonates with many today. But it should.

(Rabbi Avi Shafran is director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, a national Orthodox Jewish organization. He blogs at rabbishafran.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)