(RNS) — The prospect of studying Talmud for a week seemed intimidating to Noah Rubin-Blose, who grew up culturally Jewish and wasn’t too familiar with the Hebrew letters, much less the central texts of rabbinic Judaism.

But the opportunity to spend time with queer Jews was just too tempting. So Rubin-Blose, a trans man, signed up for Queer Talmud Camp a few years ago.

“It felt like coming home,” he said of the experience, a one-week immersive offered by Svara, a 20-year-old yeshiva for queer and trans people. “To be in a room with 80-100 queer Jews studying and singing was really meaningful.”

He was hooked.

Rubin-Blose returned to the adult camp the following year and the year after that, too. He signed up for additional Svara classes after the camp went on hiatus during COVID. He became a “fairy,” a term Svara uses for a teacher assistant, and later a fellow at the yeshiva.

Now the Durham, North Carolina, resident is studying for rabbinic ordination at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College outside Philadelphia.

Noah Rubin-Blose is a fellow at Svara, a queer yeshiva, and is also studying to be a rabbi at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, where he poses by a “Trans Lives Are Sacred” mural. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Queer and trans Jews are reshaping the contours of American Judaism, and Svara, an online-only learning forum, is leading the way. The yeshiva, founded by lesbian Rabbi Benay Lappe, doesn’t offer degrees or ordination. But it does offer a spiritual hub where LGBTQ Jews are reinterpreting and reshaping Jewish tradition by copying the methods used by rabbis of old.

Last year Svara enrolled some 500 queer, trans and gender nonbinary students in its courses. It had a budget of over $2 million and a year-round staff of 12.

Transgender rights are under assault in many state legislatures, with bans on gender-affirming care for minors, bathroom bills designed to exclude trans people from multi-user restrooms and legislation aimed at preventing trans girls from playing on women’s sports teams.

The Trans Legislation Tracker lists a record-breaking 494 anti-trans bills, including 36 that have already passed, this year alone. Many are drafted by conservative religious groups, such as the Christian legal powerhouse Alliance Defending Freedom, and passed by Republican-controlled legislatures.

By contrast, liberal Jewish movements have undergone a dramatic shift in their attitudes toward LGBTQ people. Both the Reform and Conservative movements, the two largest Jewish denominations, have condemned the wave of anti-trans legislation. (Orthodox Judaism is far less open to LGBTQ people, with most Orthodox rabbis maintaining that gender is unchangeable and marriage is reserved for a man and a woman.)

RELATED: Catholic nuns’ letter declares trans people ‘beloved and cherished by God’

Lappe, who was ordained in the Conservative movement’s seminary, had a winding path back to Judaism that included a sojourn in Japan where she studied Buddhism. Her own story of reclaiming Judaism and reshaping it to accommodate minority voices, such as queer people, but also people of color and the disabled, was the motivation for founding Svara in 2003.

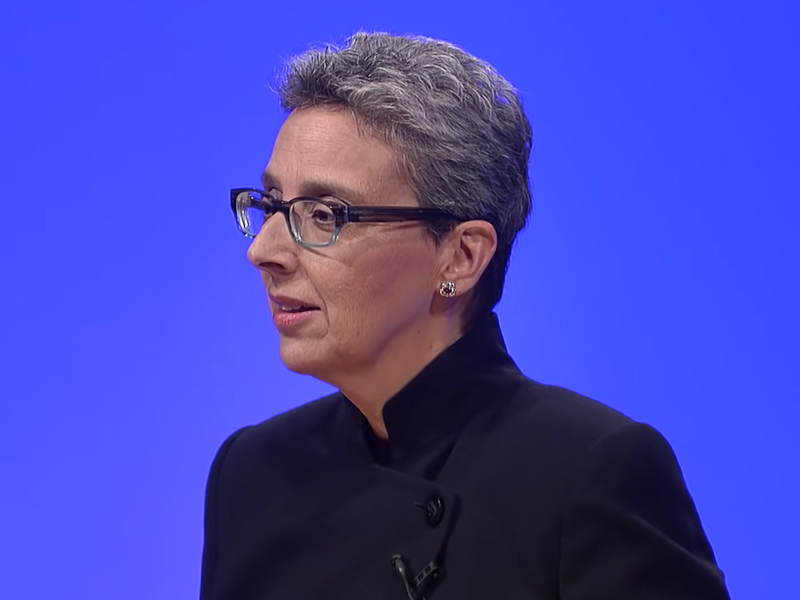

Rabbi Benay Lappe gives an ELI Talk in 2014. Video screen grab

Lappe found the key in Talmud, a multi-volume set that records the often-opposing discussions early rabbis had around Jewish law and ethics. The Talmud was written in the wake of the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in the year 70 when Jews were forced to reimagine Judaism without a central cult of sacrifices facilitated by priests.

How the Jewish sages navigated those times can offer lessons for today.

“I had grown up like most Jews with the myth that the Torah was fixed and immutable and unchanging,” said Lappe, referring to the first five books of the Bible. “I saw in the Talmud that wasn’t true at all.”

For example, she said the rabbis of the Talmud reasoned their way out of the injunction in the Book of Deuteronomy calling for the community to stone a stubborn and rebellious child. And they likewise reinterpreted the “eye for an eye” principle in the Book of Exodus. Where the biblical passage requires physical punishment for physical injuries, Talmudic rabbis beginning in the 4th century insisted the response to physical injuries should be monetary.

One of the tools the ancient sages used was “svara,” which can be translated as moral intuition.

A group of trans rabbis and scholars are now putting that methodology to work on gender issues. Svara’s 2-year-old Trans Halakha Project has just published a series of opinions (called “teshuvot”) on how trans people, or those undergoing gender transition, might approach Jewish laws around circumcision, menstruation and ritual baths.

The Trans Halakha Project has also published a series of blessings trans people might recite as a way of marking big moments, such as coming out, taking hormones or praying for safety before taking a trip.

Laynie Soloman, the co-director of the Trans Halakha Project, said the purpose of these opinions or rulings is to showcase Judaism’s process of working through multiple voices.

“It’s not about replacing existing codes with new codes about trans people but honoring the core principles of halacha as a dynamic process,” Soloman said.

Svara is a 20-year-old yeshiva for queer and trans people. Photo courtesy of Svara

Rabbis watching the work of Svara from the outside say that work is critical.

“Thirty years from now we’ll look back at this as the moment when Judaism’s understanding of gender popped open in a new way — and for everybody’s benefit,” said Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, scholar in residence at the National Council for Jewish Women.

Ruttenberg likened the work Svara is doing with queer Jews to the women’s liberation movement several decades ago that paved the path for women to publicly read Torah, be ordained as rabbis and, indeed, study Talmud, a practice once reserved for Jewish men only.

Svara attracts Jews from many different traditions, and among its students are those coming from Orthodox backgrounds where they felt confined and closeted.

Esther Mack, who grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family in Cleveland, Ohio, was studying herbal medicines when she thought to examine what the Talmud had to say about it. To find out she would have had to seek out a study partner.

“The only people I was able to find were older married men, and I didn’t want to study with an older married man,” said Mack, a 30-year-old living in Durham, North Carolina, who works as a stenographer providing closed captioning services.

Mack found Svara and began studying with Lappe back in 2015. She is now participating in a two-year Svara fellowship, a kind of teacher-training program that equips people to facilitate classes or workshops using the Svara method.

Svara also draws students, like Rubin-Blose, who comes from the opposite end of the observance spectrum. His family celebrated the Jewish holidays but did not attend synagogue regularly.

Exploring Talmud through Svara allowed him to reclaim Judaism in a way he didn’t think possible.

“One of the things I love about the Talmud is that it was written by people living under empire,” he said, referring to the Babylonian and later Roman conquests of Palestine during which much of the Talmud was written. “They were building a world underneath these structures that were oppressing them. There are so many ways we’re doing that now, too. I draw a lot of strength looking to that process that our ancestors were engaged in to think about how we care for each other and build liberating spaces while all this is happening today.”

RELATED: Clergy protest legislation targeting transgender children in Missouri