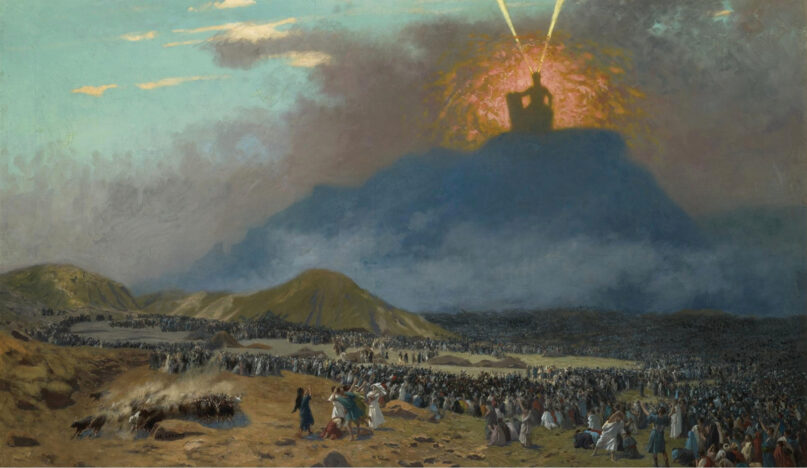

(RNS) — In the summer of 1776, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the Great Seal of the United States should depict Moses at the Red Sea, his staff lifted high and the ancient Egyptian pursuers drowning in the waters. Jefferson urged a different design: The Jewish people marching through the desert, guided by the pillars of fire and smoke.

In the 19th century, enslaved people in the United States also adopted the imagery and language of the exodus from Egypt to express the hopes they harbored to one day be free. In one famous spiritual, “Go Down Moses,” they sang of “When Israel was in Egypt land … oppressed so hard they could not stand,” punctuating each phrase with the refrain “Let my people go.” (Paul Robeson did wonders with the song in his 1942 recording.)

Similar references to the Jewish exodus from Egypt informed the American labor and civil rights movements. In his celebrated “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, the Rev. Martin Luther King pined to “watch God’s children in their magnificent trek from the dark dungeons of Egypt … on toward the promised land.” He sought to assure Black Americans that “the Israelites” suffered much before gaining their freedom, and so neither should his listeners give up hope.

The exodus from Egypt is, in a way, the mother of all liberation movements.

But to read freedom as mere release from oppression is mistaken. Passover, the holiday commemorating that freedom that was celebrated nearly two months ago, is a prelude, according to Jewish tradition, to the lesser-known holiday of Shavuot, the “Festival of Weeks,” celebrated this year on May 26 and 27. Jews have been counting the days to Shavuot since Passover.

Shavuot, sometimes called Pentecost for the Greek word for “50th,” indicating the number of days from Passover until its sister holiday, commemorates the revelation at Sinai, when God offered the people the Torah. It is customarily observed with intensive, often all-night study of the Torah.

The Passover/Pentecost binary contains a most important idea: Freedom doesn’t mean libertinism. It means the transition from meaningless, onerous oppression to servitude of a different sort, a fulfilling one: serving the divine.

Some might define freedom as lying on beach chairs on a day off from work, sunshine on their faces and a cold beverage within reach, with nothing, absolutely nothing, to do. And, to be sure, there are indeed times when we all need to relax, to recharge. But that’s not the meaning of freedom.

“Freedom,” in the Torah’s view, is release from the meaningless servitude that so many pledge to masters like money, fame, chemicals or this or that transient pleasure and entry into purposeful servitude, into something transcendent.

In fact, freedom as it’s popularly defined doesn’t even yield the happiness it promises. Winning the lottery and moving to Monaco to indulge one’s whims may be a popular daydream, but, as countless accounts have borne witness, release from economic straits and embracing hedonism have yielded more suicides than serenity.

True freedom, ironically, comes from work, from endeavoring to live a “mission-focused” life. Applying ourselves to our divine mandate liberates us from the limitations of our inner Egypts and brings true fulfillment, true joy.

Libertines, to be sure, are also acquainted with pulling all-nighters, but of a very different sort. On Shavuot, the applied study and pushing off of sleep that takes place in synagogues and yeshivot worldwide are a demonstration of the “servitude to purpose” that defines true freedom in Judaism. To most it does not look like freedom, but servitude, and it is, but with a high purpose.

The Indian poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

“I have on my table a violin string. It is free to move in any direction I like. If I twist one end, it responds; it is free./But it is not free to sing. So I take it and fix it into my violin. I bind it, and when it is bound, it is free for the first time to sing.”

It’s a poignant parable. And inadvertently apt.

Because when the Jews in the Bible left Egyptian bondage, as they prepared to embark on their path to the Holy Land, they paused to offer, as recounted in the Book of Exodus, the “Song at the Sea.”

(Rabbi Avi Shafran is director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, a national Orthodox Jewish organization. He blogs at rabbishafran.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)