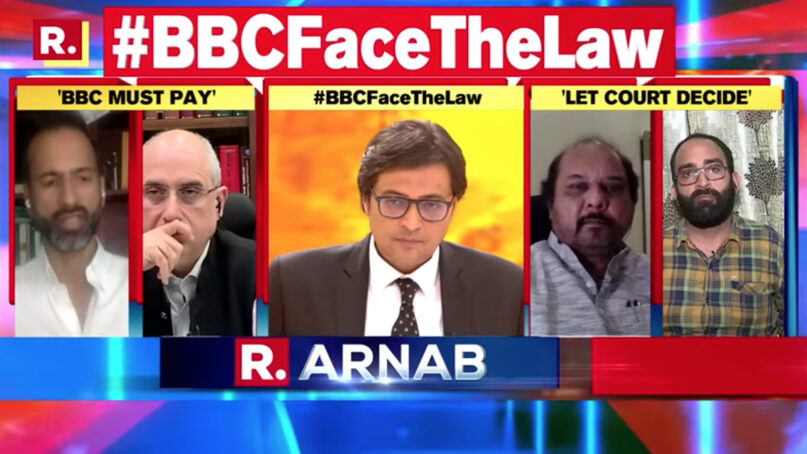

NEW DELHI (RNS) — The format of a segment that aired last month on India’s Republic News Service, commenting on a recent documentary on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s alleged role in a massacre of Muslims two decades ago, would have been familiar to American cable news viewers: The talking heads in Zoomlike boxes were arrayed around the show’s host, Arnab Goswami, dapper in a suit and fashionable glasses, as he excoriated Modi’s critics for “attempting to spread misinformation by willfully spreading falsehoods.”

The segment, spurred by a local nongovernmental organization’s lawsuit against the BBC, the documentary’s producer, was titled, “BBC Gets Notice over PM Modi Documentary: A Lesson For Western Media?”

Under Modi, however, India’s TV news channels have readily followed the lead of their American counterparts, devoting hours of prime-time coverage to politicized coverage. Republic is not alone in adopting a Hindu nationalist line, in accord with Modi’s policies. Minorities are depicted as causing problems for the broader population and facts are twisted to fit the narrative.

Hate speech is so pervasive on TV news that India’s Supreme Court said in September 2022 that it was poisoning the fabric of the country and needed to be regulated.

The Modi government, on the other hand, is rarely criticized, and anchors, like Goswami, go out of their way to condemn anyone who does so.

Seema Chishti, editor of one of India’s most prominent independent news websites, The Wire, told Religion News Service, “All values cherished by journalists, of either journalism or even basic democracy and accountability, have been pushed aside in the current environment.”

Since Modi came to power in 2014, press freedom has taken a turn for the worse, with India slipping to 161 out of 180 countries in the 2023 World Press Freedom Index report compiled by Paris-based media watchdog Reporters Without Borders. In 2016 India ranked 133rd.

In this March 7, 2021, file photo, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses a public rally ahead of West Bengal state elections in Kolkata, India. (AP Photo/Bikas Das, File)

News organizations and journalists critical of the government have seen raids on their offices and homes by income-tax authorities, including the New Delhi offices of the BBC after the release of the documentary. Other journalists have been arrested under colonial-era sedition laws.

More recently, the Modi government has proposed setting up a fact checking unit that will force social media platforms to take down content deemed to be “fake or misleading.” Many journalists have expressed concerns that it would expand the scope of government censorship on news organizations.

News organizations have pulled back on their reporting as a result and even cut reporting staff. Hartosh Singh Bal, editor of The Caravan magazine, one of the few publications that has continued to report despite harassment from the government, said that in India today, “There is no mainstream media that is independent.”

Modi himself avoids talking to the press and has held no news conferences since taking office. He instead communicates directly with the public via statements and announcements on social media platforms such as Twitter. The government often uses its posts to troll and abuse journalists, particularly minority and women journalists. Access to government functionaries has been completely cut off for those media outlets not considered favorable to the government.

Indian media do not enjoy the kind of protections afforded the press in the West. Kalyani Chadha, an associate professor of journalism at Northwestern University’s Medill School, explained that unlike in the U.S., where the First Amendment grants an absolute freedom of the press, “the Indian Constitution has a more qualified framework.”

Kalyani Chadha. Photo via Northwestern University

The media are also financially susceptible to government control, as outlets rely heavily on advertising revenue from the government. What that means is that, in a way, the media in India are subsidized by the government, explains Chadha.

Under Article 19 (1) (a) of the Indian Constitution that came into force in 1950, press rights were accorded as part of free speech guarantees. That was amended a year later to include “reasonable” restrictions, which included national security concerns. This has allowed governments in the past to muzzle the press. In the most infamous case, then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi clamped down on the media in 1975, arresting hundreds of journalists.

Successive governments have used these restrictions in their own way. Abhinandan Sekhri, co-founder and CEO of Newslaundry, an independent news website, said he faced several roadblocks with the Manmohan Singh regime, which preceded Modi. “No government is fond of a truly independent media.”

Adding to the challenges is the increasing corporatization of media as well as shrinking profits and ownership changes. In 2014, India’s largest company, Reliance Industries, owned by billionaire Mukesh Ambani, took over one of India’s largest media companies, Network18 Media, which co-owns CNN-IBN with Warner Bros., and other channels.

More recently, Gautam Adani, India’s richest man, acquired a majority share in the TV news network NDTV that was long respected for its balanced journalism. Many senior journalists were forced to leave.

But Modi has put the most pressure on television; though he avoids meeting the press, he seems to realize that no politician can exist without television. He also uses it to reach his supporters directly. Sandeep Bhushan, a television journalist and author of “The Indian Newsroom,” said Modi knows the power of the medium and weighs his attire and even his demeanor carefully when appearing on TV. “He knows the camera is a performance driven medium,” said Bhushan, “and he also knows that previous governments have lost elections as a result of media coverage.”

Modi’s friends in television, whether wealthy media barons or popular hosts, know that Modi’s message can deliver viewers. As in the U.S., they have been complicit in muddying the concepts of objectivity and truth in televised journalism.

The result is what some journalists say is the worst period for press freedoms in memory, and by implication for freedom in the country as a whole. “We claim to be a democracy but the ability to express views in the media has taken a big hit,” said Chishti, whose news organization has faced difficulties with the Modi government. “Media is the only institution that can be a check on the government and tell people clearly all that is going wrong or the government is getting wrong, but it has been muzzled. Any sort of government criticism can lead to a vicious backlash.”

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Seema Chishti’s name. Religion News Service regrets the error.