JERUSALEM (RNS) — When Dina Kraft read “Anne Frank: the Diary of a Young Girl” as a teenager in the 1980s, she felt an instant connection with the vivacious young Jewish girl who chronicled her life while hiding from the Nazis in a secret attic in Amsterdam.

After discovering the Franks’ hiding place, the Nazis sent them to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Later, Anne and her sister, Margot, were transferred to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they died of typhus and starvation.

“Anna seemed like someone who would be my friend. She was a chatterbox and got in trouble for talking in class. She seemed vibrant and personable and real,” said Kraft, using the name Anne herself used. When Kraft learned of her fate, “I felt bereft, like I had lost a friend.”

The famous diary resonated with Kraft for another reason: Her grandparents fled from Europe to New Zealand with Kraft’s mother, then an infant, in 1939, as the Nazis were advancing across Europe.

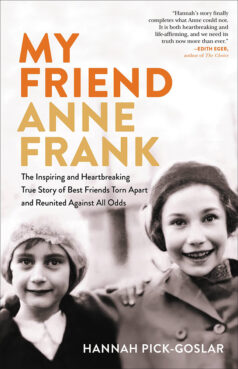

So when Kraft, a Tel Aviv-based journalist, was asked to co-author the memoir of Hannah Pick-Goslar, a dear childhood friend of Anne Frank and a survivor of Bergen-Belsen, she leapt at the opportunity. The resulting book, “My Friend Anne Frank,” was released on June 6.

Hannah (Hanneli) Pick-Goslar holding a photo of Anne Frank. Photo © Eric Sultan

Sadly, Pick-Goslar didn’t live to see her book published. She died in October 2022, just shy of her 94th birthday.

Like Anne Frank’s family, the Goslar family were German Jewish refugees who found a temporary haven in Amsterdam. The families lived in adjoining buildings. From a young age, Anne and Hannah attended school together and quickly became inseparable.

The book is filled with anecdotes that only Pick-Goslar could share.

“Hannah Pick is one of the few people who could offer the world a far more realistic portrayal of who Anne Frank really was,” Efraim Zuroff, a Holocaust historian and Nazi hunter, told RNS.

In her memoir, Pick-Goslar recalls the Franks “were our regular guests for Shabbat dinner.” Anne’s father, Otto, was “fully secular” and “never learned Hebrew, but he heard the prayers so many times at our table that he’d memorized them, and he could join in.” Anne’s mother, Edith, “who grew up in a more traditional Jewish home, keeping kosher and attending synagogue, appreciated the ritual and familiarity of these Shabbat meals.”

“My Friend Anne Frank” by Hannah Pick-Goslar with Dina Kraft. Courtesy image

Remarkably, even the tightening grip of Nazi oppression didn’t prevent Anne from celebrating her June 12 birthday in typical Anne style. In the spring of 1942, as the Nazis imposed curfews on the Jews and forced them to wear yellow stars with the word “Jew” emblazoned on it, Anne pressed an envelope into Hannah’s hands.

“She smiled and watched me open it. An invitation to her 13th birthday party on Sunday. On the invitation there was also a cinema-style ticket with my seat number.

‘Father’s renting a film projector again so we can watch Rin Tin Tin!’ Anne explained. Anne and (her sister) Margot always had the nicest birthday parties.”

Less than a month later, when Hannah’s mother sent her to borrow the Franks’ kitchen scale, the teen discovered the Franks had vanished.

“I walked through the rooms gingerly,” Hannah writes. “It was as if everything was suspended in that exact rushed moment of the Frank family’s departure. The dining room table was still covered in breakfast dishes. The beds were unmade. It felt wrong to be there without them, like we were sneaking in. I’d never been in their home without them there.”

“The Franks wanted it to look like they left in a hurry. This was their cover story,” said Kraft, who began to interview Pick-Goslar in March 2022, usually for hours at a time either on Zoom or in Jerusalem.

“Hannah was in failing health but completely sound of mind. She seemed energized by talking,” Kraft said.

Even so, the interviews were emotionally draining for both author and co-author.

Hannah Pick-Goslar and Anne Frank in their classroom at the 6th Montessori school in Amsterdam, 1938. Hannah is on the far left, seated towards the back, and Anne stands in a white pinafore to the left of their teacher. (Source: Anne Frank House, Amsterdam.)

“Hannah and I both had bad dreams” following some of their interviews, Kraft said. “As a journalist, I try to create a bit of distance, to remind myself that their trauma is not my trauma. But Hannah — who had wanted to write a memoir for decades — “had no such emotional wall” as her memories came flooding back, observed Kraft.

Pick-Goslar and her little sister were the only ones in their family to survive the war. They were imprisoned in Bergen-Belsen for 14 months.

It was there, toward the end of the war, that Pick-Goslar learned Anne Frank was imprisoned in an even worse part of the camp, on the other side of an impenetrable wall patrolled by Nazi guards.

Hannah managed to give Anne some scraps of food donated by other imprisoned Jewish women. The girls were able to speak, but not see each other, three times before Anne perished.

“The Anna who Hannah encountered is broken by typhus,” Kraft said. “Her beautiful hair has been shaved. She’s starving. She tells Hannah about the gas chambers. Anna cries, ‘I have no one left.’ They sit on each side of the fence weeping.”

Dina Kraft. Courtesy photo

While the memoir documents the Nazis’ day-to-day cruelty as well as the decision, by the U.S. and many other Western nations, to close their borders to desperate Jewish refugees, it also reflects Pick-Goslar’s infectious optimism and sense of purpose.

“Hannah was very funny. She had a wry sense of humor,” Kraft said.

Despite her horrific experiences, Pick-Goslar created a happy new life for herself and her sister in Israel. She immigrated to then British Mandate Palestine in 1947, the year before Israel was established.

She married, became a nurse, a mother, a grandmother and great-grandmother. Her Jewish faith sustained her.

“For her, religion was like a compass,” Kraft said. “It gave her a community and a framework and a continuity of the life her parents gave her. She recalled her father wrapped in his prayer shawl, praying with a full heart. She wasn’t angry at God. God was her lifeboat.”

According to Pick-Goslar’s daughter, Ruti Meir, “Mom was full of life and optimistic and kept to the path of faith that she got from her parents’ home. Also, during the Shoah, she saw her father maintain his faith, giving Torah lessons that raised people to a higher spiritual level. This is also how she built her home and taught her children.”

Kraft considers the memoir an extension of the story that Anne Frank never got to tell — of events that unfolded outside the Franks’ hidden attic, and after the Holocaust ended.

“But it’s also the story of survival that Hannah was able to experience. That was the most beautiful task of writing this book. Sharing not only the account of the trials and dehumanization and degradation she had to endure, but the story of coming back to life.”

Hannah Pick-Goslar, left, and younger sister Gabi Goslar with their aunt Edith after the war, c. 1947. Photo courtesy Penguin Random House