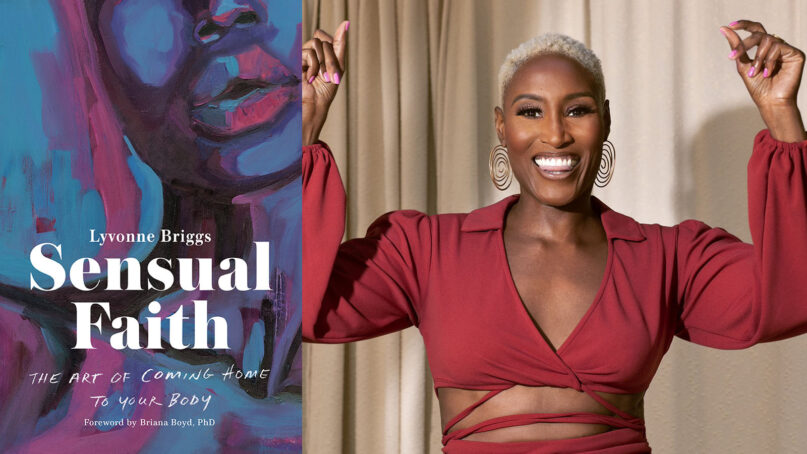

(RNS) — Lyvonne Briggs describes herself as “a Black woman spiritual leader who is no longer at war with her body.” Her mission, in her new book, “Sensual Faith,” is to help other women stop being at war with their bodies too.

If that sounds dark, that misapprehension is dispelled in the first words of “Sensual Faith”: “Hey Boo!” Briggs addresses her readers as if they were in the room with her, and her enthusiasm rarely wanes over the course of 200 pages as she talks about pain and pleasure, healing, hurting and how our bodies are connected with the divine.

Briggs, 40, says she does not preach about anything she hasn’t personally experienced — the roller coaster of marriage and divorce, conception and miscarriage. She writes about surviving sexual assault. A New Yorker, Briggs attended Yale Divinity School and Columbia Theological Seminary and worked as an assistant pastor in New Orleans before founding Beautiful Scars, a storytelling and personal development consultancy.

Religion News Service sat down with Briggs talk about her audience, her journey and the act of spiritual, sensual and sexual healing.

The voice you use in the book is unexpected but refreshing. How did you decide to write it this way?

I’m a Black woman writing for Black women, and Black women have vernacular, colloquialisms and an energy about us. There’s very Black-girl-specific language — even, in some parts, very Black-church-girl-specific language — that I use intentionally because I wanted Black women to know that, one, I’m writing to you. That we can carve out this really beautiful, authentic, sacred space together to explore really big, hard, tough issues. There’s something to be said about writing a book about radical hospitality using language that’s a tool and an invitation into said radical hospitality.

So you’re writing primarily for Black women?

In my mind’s eye, I’m talking to Black women, 18 to 45, currently or formerly “churched,” who always had this hunch that there’s got to be more to it than this — religion, faith, God, spirituality. Growing up hearing sermons about “If you have sex before marriage, you’re going to hell.” Why I gotta go to hell if I’m having consensual sex? There are harmful ideologies that attack our queer kin, right? Why I gotta hate gay people if I love God? That doesn’t make sense.

Lyvonne Briggs. Photo © Bukunmi Grace

When I think of specific readers, I’m thinking of women, like me, in their 20s, in grad school, being introduced to new concepts and thinking, “I really want to go to a yoga class, but I heard yoga is demonic. Can I go to yoga or not?” Women in their 30s navigating engagements, marriage, divorce, all kinds of reproductive health things. I’m thinking of women in their 40s navigating divorce and owning their sexuality now that they’re thinking about life after the kids leave the nest.

It’s for women who want to feel full, whole, at ease and at home in their bodies, no matter what age they’re at.

But something I get all the time is, “If I’m not a Black woman, can I read this book?” The answer is absolutely yes. It’s a womanist sacred text that centers the liberation of Black women and femmes. When Black women and femmes are free, everybody else is gonna be free. When you are reading a book that does not center you, it’s not your job to try to center yourself. As a friend said: “It’s your job to empathize. Build your empathy muscle, learn all you can, take what’s for the journey and pass it on.”

I will also say you do not have to be a Christian or even religious to engage with this book. I know the word “faith” can be very off-putting to some people, but I define it as what you say you believe. If you believe all Black lives matter, then show me that. Are you voting like you believe that? Believe trans kids are worthy of protection? Are your dollars going to support people who support trans kids? Like, show me your faith in action. It doesn’t always have to do with the church.

What does “sensual faith” mean to you?

It’s a framework that’s been in the making for decades. No matter where I was in life, at home, church, school, questions about my being and my experience would always come up. There would be walls put up, whether it was in the classroom or the sanctuary, when I wanted to talk about really hard things. I started to learn that the things the church was teaching me were bad, or evil or demonic, were what I needed to be at home in my body. I realized that when I felt comfortable in my power, that was a problem for the church and for society.

I’ve started to pay more attention to my body. The more you tell me to repress, I’m like, “How can I celebrate? How can I embrace? How can I integrate?” I really wanted to center the conversation on the beauty of bodies — without centering sex, because Christians tend to hunker down on sex. Our bodies are sexual, but they’re more than sexual, and I wanted to tap into the divinity of the human condition, which is not what Christians are doing.

You write about recovering from sexual assault and that the church told you “It’s in God’s plan” or “The Lord is testing you.” What should they have said?

“I believe you.” It boggles my mind as a pastor, that there are people who will believe that God split open the Red Sea, a prophet survived an encounter with a whale, but when a person comes forward about assault, they don’t believe that. All of the rationalization goes out the window the moment I honor and see you. “I believe you” says: “You don’t have to prove here, you’re not on trial. I support you, I may not know how to support you, but I’m gonna figure it out.”

Your chapter on masturbation comes at the end of the book. It feels as if you wanted readers to get comfortable before you talk about it.

Precisely. I set up the historical, ethical overview of how we got to this place, then (write about) what we have to unlearn. I trust that pleasure is the pathway to liberation for Black women and those who support us. But we first have to decolonize it, remove the stigma. We have to unlearn the idea that God doesn’t want us to experience pleasure.

Masturbation, for me, is a tool of healing and reclamation for survivors. It’s the ultimate form of consent. If you bring (pleasure) to yourself, you’re not relying on someone else who could be harmful for you.

Which part of the book would you point to as key to its mission?

At the end of every chapter, you’re going to have a Scripture to celebrate you, an opportunity to reflect and affirm. You don’t have to do anything but engage, be selfish and center yourself. You don’t have to think about anybody else while you’re reading this book. At the end of every chapter is a consensual hug.