(RNS) — Many Americans have long accepted that slavery was America’s original sin.

But what if it wasn’t? What if that original sin stretches back 500 years to the forced removal and, in many cases, extermination of Native Americans by America’s white European settlers?

And what if there’s a religious decree, dating back to the late 15th century, that gave divine sanction to the robbery, enslavement and violent oppression of nonwhites?

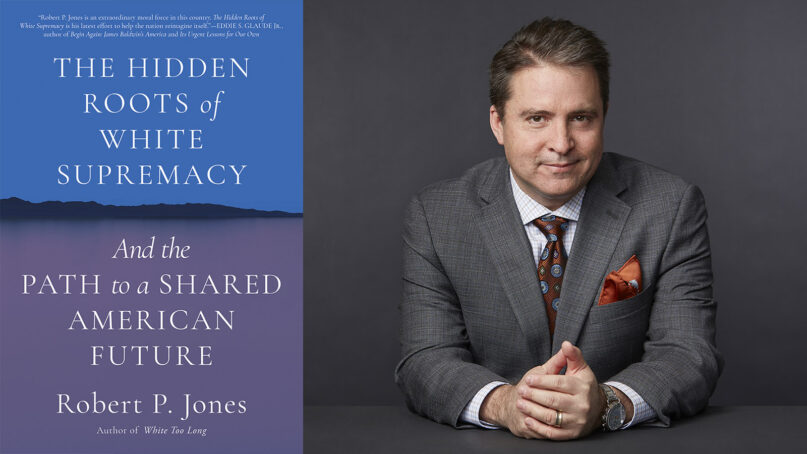

That’s the argument pollster Robert P. Jones makes in his new book, “The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future.”

The book, which releases Sept. 5, locates the origin of America’s race problem in the Catholic Church’s Doctrine of Discovery. In that 1493 edict, Pope Alexander VI provided a blueprint for seizing “undiscovered lands” that were “not previously possessed by any Christian owner” and subduing the people on that land.

Jones makes the case that the doctrine’s underlying worldview of divine entitlement shaped the way America’s white, European Christian settlers saw themselves and their mission and justified outbursts of violence, dispossession of Indigenous people and the enslavement of Blacks.

In his book, Jones focuses on three sites where the scars of white supremacy are, as he says, “carved across the land” and where earlier violence begot more violence: the Mississippi Delta, where Choctaw Indians were forcibly removed from the land and where, in 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered; Minnesota, site of the mass deportation of the Dakota people and the execution of 38 Dakota men, followed in 1920 by the lynching of three Black circus workers; and finally, Oklahoma, where the Osage people suffered theft and forced assimilation and where the Tulsa race massacre took place in 1921.

“If we do the hard work of pushing upriver, we find that the same waters that produced the Negro problem also spawned the Indian problem,” Jones writes. “If we dare to go further, at the headwaters is the white Christian problem.”

Religion News Service spoke to Jones, president and founder of the Public Religion Research Institute, about his book and how a 500-year-old church doctrine — recently repudiated by the Vatican — persists in the rise of today’s anti-democratic defense of white Christian nationalism. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

When did you first come across the Doctrine of Discovery?

It wasn’t until I was really digging in and reading Native American scholars who were writing about the origins of the country. People like Vine Deloria Jr., for example, had a piece called “An Open Letter to the Heads of the Christian Churches in America,” that he wrote in the early 1970s, where he talked about the Doctrine of Discovery and the centrality of that doctrine to the way white Christian people treated Indigenous people in this country from its inception. Over the last 50 years it’s been a common theme, particularly among Indigenous authors and authors of color. But, you know, I went to a Southern Baptist seminary, and even in my Ph.D. program at Emory, it just never figured prominently in the history to which I was exposed.

Tell me why you chose the three sites that you did.

For different reasons. I’m from Mississippi. So that was a story close to home. On the ground in Tallahatchie County — where events happened — there were no markers telling the story of Emmett Till prior to 20 years ago. So if you had driven through the Delta in the year 2000, you would have seen literally nothing there. Tulsa, Oklahoma, had been on the national radar because we had just passed the 100-year anniversary of the Tulsa race massacre. I thought there was more of a story to tell there, particularly how it connects with Native American history in Oklahoma. And then, I didn’t want to be accused of cherry-picking stories from red states or the South. I wanted to write also about something in the far north. I had come across the story of this lynching in Duluth, and in my last book, “White Too Long,” I wrote just a couple of pages about it, and I realized it was a much bigger story to tell there. And so I went back to that story again.

You mention The New York Times’ 1619 Project and your own realization of its limitations — that it doesn’t tell Native American history. Was that what led you to this book?

I think the root of it is bigger than that. The 1619 Project has been vitally important for resetting the way we think about American history. But I think we need to push back even further. We have more than a century of European contact with Indigenous people. That history is really important. The 1619 Project expanded the aperture beyond what we see on postage stamps and patriotic paintings of a bunch of white men gathered in Philadelphia around the table with their quill pens. Getting us beyond that picture of the beginnings of America was a herculean effort and vitally important. It’s just that I think we need to kind of keep moving to tell the story on a little bit of a bigger canvas.

So, is the Doctrine of Discovery America’s new origin story?

I want to be careful here not to commit my own sin of overreach — to say this is the date that we should declare as our nation’s beginning point because there are certainly things that led up to that point. But there are these kinds of watershed moments and, among them, 1493 is certainly an important one. Many of us learned that in 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue, as the poem says. But it’s really the year he goes back to Spain and gets this permission and stamp of approval from the sitting pope at the time, Alexander VI, that puts the kind of full imprint of the church on conquering any lands that are possessed by non-Christians. If you were not Christian, then you didn’t have any inherent human rights.

How do you hope to change the conversation with this book?

We’re at a moment where we are arguing over history. We’ve seen Arkansas not counting AP African American history and fights in Florida over the status of AP American history. These are all about our origin stories. We’re caught in this moment because of the changing demographics of the country. What I’m hoping the book does is tell a bigger story.

What we often get — and I say as someone who was educated in Mississippi public schools — are words like “pioneers,” “settlers,” these kind of innocent words that I think don’t do any sort of justice to the violence that was wielded. Facing that history squarely is important if we’re going to be honest with ourselves about how we arrive to the place we’re at.

Frankly, everywhere you go in the country, the place names testify to this history. In the Mississippi Delta, there’s Tallahatchie County, a Native American name. There is DeSoto County right next door, which is named for Hernando de Soto, the Spanish conquistador who comes and claims all of that Mississippi watershed for Spain using the logic of the Doctrine of Discovery. If we’re going to get to a shared American future, we have to have a shared American story. And I think that is vitally important and white Christians have to be more honest about what that history is.

You strike a note of hopefulness about these three places for grappling with the tragedies that took place there. Are you more hopeful about America’s future?

Part of what I did for the book is I interviewed people who have been involved in these very local efforts and not in easy places. The Mississippi Delta is a tough place to do this kind of work. There’s not a lot of resources, it’s rural and fairly poor. And yet here, this intrepid group of citizens got together — white descendants of plantation owners, organizing alongside descendants of enslaved people and sharecroppers. I think that’s a real mending of the fabric at the very local level. Just a few weeks ago, we had President Joe Biden declare a new national monument to Emmett Till to be permanently funded, maintained and part of the National Park system.

You’re a public pollster. What’s the relationship between what you do at PRRI and your books about American history?

These books are written in my name. They’re not PRRI books. But there’s a question that we’ve asked for a couple of years now that really is at the heart of the matter: Are we a divinely ordained promised land for European Christians, or are we a pluralistic democracy where we are multireligious, multiracial and everybody stands on equal footing as citizens?

We have been struggling between these two questions our entire history and they’ve been fairly unresolved. About 30% of the country will say, for example, the United States was intended by God to be a promised land where European Christians could set an example for the rest of the world. But that means that by a margin of 2-to-1, Americans reject that vision of the country. You would think that might mean, OK, well, debate over. Let’s move on. On the other hand, it’s captured a majority of one of our two political parties. So it means we’re fighting over the way we are.

We are at this hinge point where this question is getting asked in a very forthright way. We’ve been there at other times: Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement. But now the demographics have changed so there’s no longer the supermajority of white Christian people in the country. So now the answer to that question matters in a way it didn’t for past generations. The books add social, historical and cultural context to the kind of things we’re capturing in public opinion polls today. When you understand the longer sweep of history, those things become less mysterious.

(This story was was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.)

RELATED: Emmett Till memorialized in monument that includes Chicago church