(RNS) — On the eve of Rosh Hashana 60 years ago, Rabbi Milton Grafman stood up before his packed congregation at Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, Alabama, and confessed that he had no prepared sermon to deliver.

Just three days earlier, on Sunday morning, Sept. 15, 1963, four Ku Klux Klansmen had dynamited the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Birmingham’s first Black church, killing four girls. Grafman had been so involved in the aftermath, he said he’d all but forgotten about the holiday.

And so he would speak extemporaneously of things that were on his heart. What followed was a true cri de coeur.

“I’m just as sick at heart as you are about what’s happened in our city,” he said. “I’ve been sick about it for years. Anybody with a shred of humanity in him could not have been but horrified what happened.”

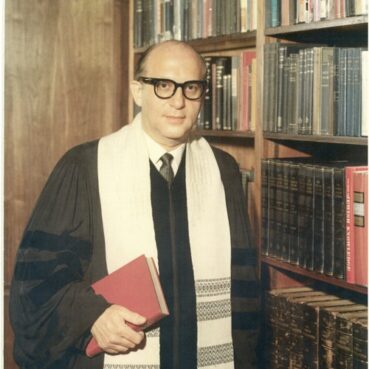

Rabbi Milton Grafman. Courtesy photo

But what troubled Grafman’s heart in that season was not just the church bombing. He’d been one of the group of eight leading white clergy who had issued a statement five months earlier, on Good Friday, opposing the demonstrations being organized by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the city. “We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized,” the statement read. “But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.”

In response came King’s thundering “Letter from Birmingham Jail” — a document addressed to the eight clergymen but planned in advance and intended for a national media audience.

“I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate,” wrote King. “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Council or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.”

And: “I came to Birmingham with the hope that the white religious leadership of this community would see the justice of our cause and with deep moral concern, would serve as the channel through which our just grievances could reach the power structure. I had hoped that each of you would understand. But again I have been disappointed.”

In fact, as Samford University historian S. Jonathan Bass shows in his fine book on this crucial episode in the Civil Rights Movement, King’s program of marches and demonstrations was losing steam in the spring of 1963. Before Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor sicced his dogs and fire hoses on the marchers, the eight clergymen’s case for a more moderate approach was plausible.

But in the wake of the violent repression, the addressees of King’s letter were inundated with passionate denunciations — and none of them more than Grafman. To Grafman’s co-religionists in the North, and not least national organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League, this rabbi was the exemplar of all that was wrong with white people of “goodwill” in the South.

“I wish you could read these letters that have come to me from Jews who said that they’re ashamed to be Jewish because I’m a rabbi,” he told his congregation.

Standing at the front of Emanu-El’s circular sanctuary, modeled on the Pantheon in Rome, Grafman denounced liberals and reactionaries alike as, in his view, posturing on civil rights for political purposes. Nor were his remarks lacking in moments of arrogance and self-pity.

But his strongest words were reserved for the members of his congregation who were content to sit at home lamenting the injustice but doing nothing. He himself had received death threats from segregationists for speaking out for racial justice, for signing letters to the editor in favor of accepting the law of the land.

“This isn’t the way I like to talk on Rosh Hashana,” he said. “These are terrible times and it’s time to stand up and be counted. It’s time to do so. it’s time to pay the price whether it’s in personal safety and security. … Are you ready to pay the price because if you’re not, God help this city.”

After retiring from the Emanu-El pulpit in 1975, Grafman spent his last 20 years as a public figure in Birmingham, working for the betterment of his city. It seems, however, that he never fully recovered from King’s letter — from being collateral damage on the road to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A tape recording was made of Grafman’s Rosh Hashana sermon and it’s been posted online. As a living moment in history, it’s priceless.