(RNS) — From the Black clergy who helped guide the Civil Rights Movement to evangelical Christian pastors who aligned with the Republican Party in the 1980s, clergy in America have often played an outsized role in America’s political conversations. As our nation braces for a highly competitive and challenging presidential election, religious leaders will continue to influence political choices in their congregations and beyond.

Often overlooked is the role of mainline Protestant clergy, in part because of the well-documented story of white mainline Protestant decline: Through the early 1960s, about half of Americans identified as white mainline Protestants; today, as PRRI, the research firm I lead, showed in its 2022 Census of American Religion, just roughly 14% do.

Mainline Protestant clergy’s views on politics, however, warrant attention. Not only have the membership numbers of mainline Protestants stabilized in the past few years, but their churches harbor some of the last vestiges of ideological and partisan diversity among religious Americans. In 2020, while most white mainliners voted for Donald Trump in 2020 (57%), a sizable minority cast their ballot for Joe Biden (43%); by contrast, 84% of white evangelical Protestants backed Trump, and 91% of Black Protestants voted for Biden.

This political diversity might lead some to assume that mainline clergy ministering in predominantly white churches avoid mentioning politics in the pulpit. Previous studies, including a 2008 survey report by PRRI, show that mainline clergy are often more politically progressive than those who sit in their pews. By contrast, Black Protestant and white evangelical clergy are much more politically aligned with their congregations, so the decision to speak out politically from the pulpit may be less fraught.

Our new survey finds this political clergy-laity gap alive and well among mainline Protestants. In the last year, PRRI surveyed more than 3,000 lead pastors from the seven largest mainline Protestant denominations, comparing their political views with those of white mainline, nonevangelical Protestants who regularly attend church from our Health of Congregations survey, released in May.

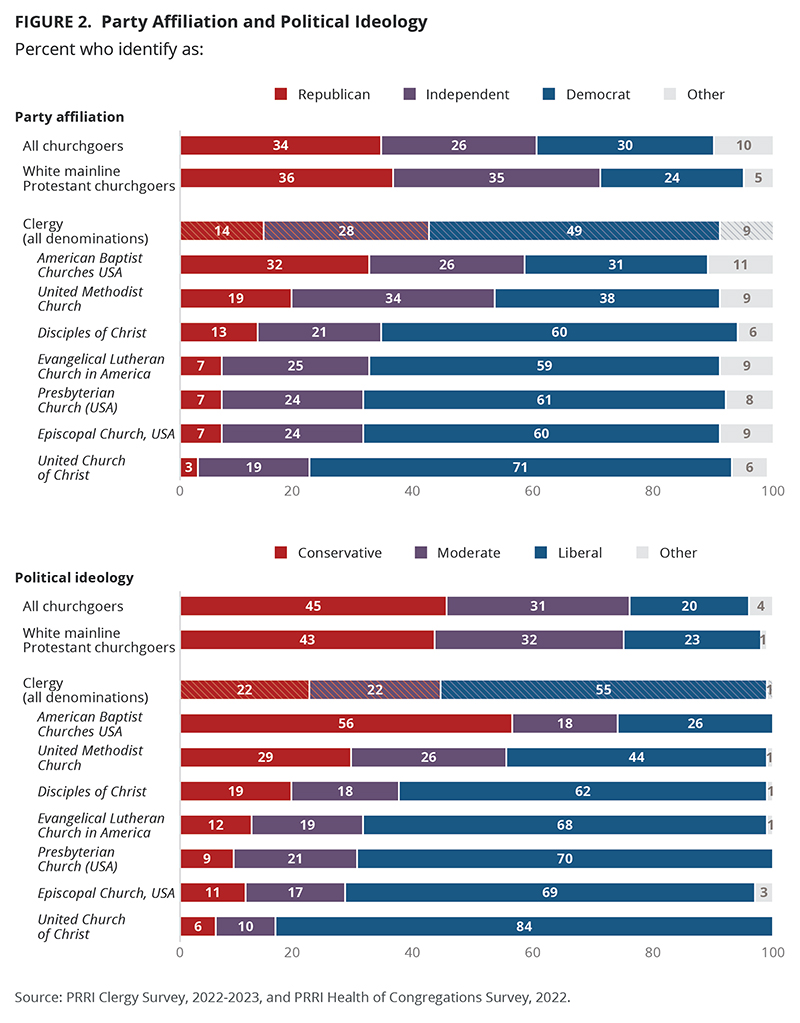

Among clergy, we found that about half identify as Democrats (49%) and 28% identify as politically independent; only 14% identify as Republican. White mainline Protestant churchgoers, meanwhile, tend to identify more as Republican (36%) or independent (35%), compared with 1 in 4 who identify as Democrats (24%).

“Party Affiliation and Political Ideology” Graphic courtesy of PRRI

Mainline Protestant clergy are also more than twice as likely as white mainline Protestant churchgoers to identify as politically liberal (55% to 23%, respectively). By contrast, 43% of white mainliners in the pews identify as conservative.

These partisan and ideological differences are matched by differences between mainline Protestant clergy’s attitudes and those of churchgoers when it comes to LGBTQ rights, abortion and cultural change. For instance, nearly 7 in 10 mainline clergy (69%) oppose allowing small business owners to refuse to serve gay or lesbian people if doing so violates their religious beliefs, compared with 57% of white mainline Protestant churchgoers.

Nearly three-fourths of mainline clergy (73%) oppose the Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, compared with fewer than 6 in 10 of white mainline Protestant churchgoers (57%). And while nearly 2 in 3 white mainline Protestant churchgoers (64%) agree that America is in danger of losing its culture and identity, that sentiment is shared by just 37% of mainline clergy.

At the same time, Protestant clergy feel a sense of urgency about the need to speak to the important political and social issues that define our times. Eight in 10 mainline Protestant clergy (79%) agree that their congregations should get involved in social issues, even if that means having challenging conversations about politics. By contrast, fewer than half of white mainline congregants (43%) nationally agree with this sentiment.

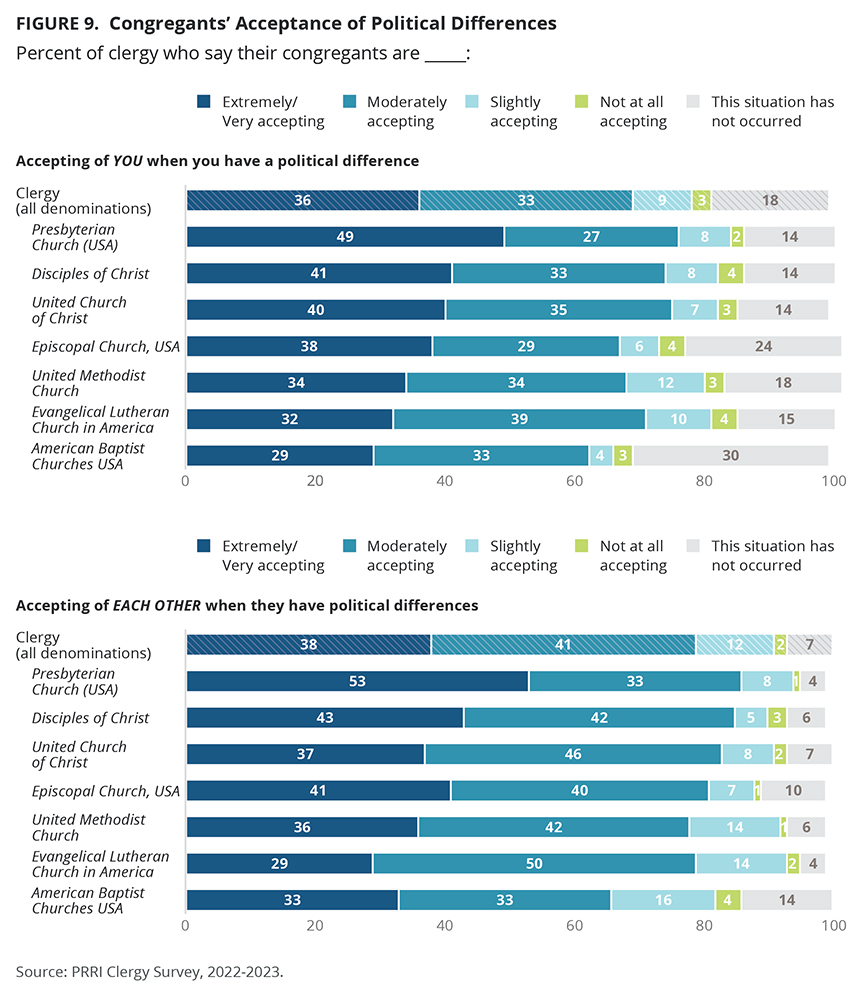

Yet in the vestibules of our nation’s mainline churches are precisely where such important discussions may get traction. Our survey found a lot of grace to be had in those very places. Nearly 7 in 10 clergy (69%) say their congregations are extremely, very or moderately accepting of them when their political views differ from congregants’. Moreover, 79% of clergy report that their congregants are generally accepting of one another when political differences arise.

“Congregants’ Acceptance of Political Differences” Graphic courtesy of PRRI

Unsurprisingly, half of mainline clergy who say their congregants are only slightly accepting of their political differences, or are not accepting at all, report feeling emotionally drained from their work on a regular basis. Of those whose congregants are generally accepting of their political differences, only 28% say they are emotionally drained by work.

But priests and ministers dealing with congregants who are unaccepting of their political differences make up a relatively small percentage of mainline Protestant clergy as a whole. Instead, there is strong agreement among all clergy that providing a faith perspective on pressing social concerns is an important part of a church’s role in its community. It is notable, too, that more than 7 in 10 clergy in our study expressed a desire to collaborate more with other churches in their community.

While our survey found that many mainline clergy are sober about the challenges their churches face in the future, in terms of their membership levels, programming for children and diversifying their churches, most mainline clergy remain optimistic about the future and are proud to be affiliated with their congregations. If they can hold onto this optimism while cultivating healthy political discourse among their flock, our country will be the better for it.

(Melissa Deckman is CEO of PRRI. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)