(RNS) — When Linda Ambrus Broenniman was 27 years old, a family friend let slip that Broenniman’s father was Jewish.

As one of seven children in a middle-class Buffalo, New York, family, she had grown up attending Catholic Mass each Sunday alongside her parents and siblings.

She knew her parents were born and raised in Hungary and came to the United States to escape communism and establish their careers as physicians. Why would her father conceal his Jewish past?

Broenniman gently asked but was rebuffed. Thirty-five years later, her mother received notification that the Israeli government was about to honor her as a Righteous Among the Nations, a designation recognizing non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust.

Linda Ambrus Broenniman. Photo courtesy Broenniman

This time, Broenniman was determined to get answers. But her mother was already suffering from dementia and her father wouldn’t budge. Five years later, when her parents’ home caught fire, a rescued box with dog-eared files, photos, postcards and documents, mostly in Hungarian and German, set her on a seven-year journey to discover the truth of her family’s past.

“The Politzer Saga,” a book she wrote, tells the remarkable story of eight generations of prominent Hungarian Jews stretching back to the 18th century who went by the name Politzer. (One of her ancestors married into the better-known Hungarian-American Pulitzer family.)

On the eve of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, as Jews around the world gather to wrestle with the questions, “Who have we been, and who will we be?” Broenniman has her answer. She is a Politzer, a descendant of a long line of doctors, lawyers, merchants, bankers, developers, art collectors and musicians.

Last week, Broenniman, who is 67 and lives in Great Falls, Virginia, returned from Hungary where a permanent exhibit of her family’s history was officially dedicated on the third floor of Budapest’s Moorish-styled Rumbach Street Synagogue.

Broenniman traveled frequently to Hungary to do historical research for the book, working alongside a Hungarian lawyer and genealogist, Andras Gyekiczki, to whom she dedicated her book.

Her account of the Politzer family takes in 300 years of Hungarian-Jewish accomplishment, struggles and setbacks. The story culminates with the Holocaust, in which more than half a million Hungarian Jews were killed, including Broenniman’s grandfather, Sandor Ambrus, who died (either in Dachau or on forced marches shortly before the camps were liberated).

The Politzer Saga Exhibit on the third floor of the Rumbach Synagogue in Budapest, Hungary. Photo courtesy Linda Ambrus Broenniman

The Ambrus family converted to Catholicism just as the war began, mostly so Sandor could keep his professional license and clients. It didn’t help Sandor, nor his son, Broenniman’s father, Julian ,who was taken to a forced labor camp. Julian eventually managed to escape and was hidden by his fiance, and later wife, Clara, Broenniman’s mother.

RNS spoke to Broenniman about her family’s incredible history, about identity, belonging and faith. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about the gathering to honor your family at the Rumbach Synagogue in Budapest.

The exhibit opened in the middle of COVID. So there were no celebrations; it was very subdued. This gathering on Sept. 2 was to thank everyone who had worked on the exhibit, because that had never really been done, and then to bring together family and friends who cared about the exhibit and really just to have an opening. There were well over 50 people there.

Tell me a little more about what led you on this voyage to discover your family’s history.

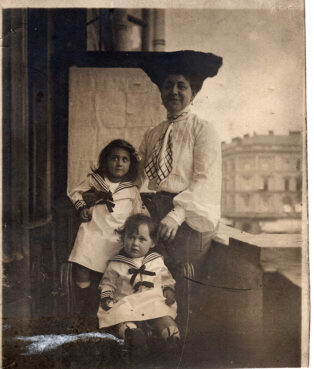

Margit Politzer and her two daughters, Lili and Erzebet, in Budapest, Hungary, in 1904. Photo courtesy Linda Ambrus Broenniman

There was still a shroud of secrecy in my family, and it felt like it was so hard to penetrate that. My father, to his dying day, never admitted he was Jewish. But then finally after the fire and after we found that box, I just decided it was time. I needed to find the truth. I had no idea what to expect, but I wanted to understand who I was and where I fit in the world. I really wanted to learn about my great-grandmother, Margit (Misner Politzer) because I had heard stories about her. She was obviously revered by both my father and my mother. My mother had told me stories about this amazingly strong woman who was all about service and caring for others. Margit used to have an open house once a week and anyone could come and ask her things — to help find a job or to help with medical bills. She often sent people to doctors she knew and would pay for their health care. She paid for a lot of children’s education, and she would give food and in some cases money to people in need. And so she was a role model, and I really wanted to find the truth.

Why do you think your father resisted telling you about his Jewish roots?

The only thing I can say is he was such a complicated man, and he was a remarkable person. I mean, he, like Margit, was all about service. He was a doctor. He wanted to cure cancer, and he was all about service, but I’m sure he carried some PTSD with him. I think he never dealt with what he had gone through. We’ll never know what he actually went through, but clearly there was a pact of silence. I wish I could get inside his head. I tried, but never could.

Your father’s parents converted to Catholicism in 1938 and your father a year later, is that right?

My grandfather was a lawyer and had to continue to try to put food on the table. I really believe they converted because they had to try to survive. In their heart of hearts, they were still Jewish, and they weren’t going to change.

The Politzers wanted so much to be part of Hungarian society, and they were rebuffed through the years because of their Judaism. Why do you think they struggled so much to integrate?

Linda Ambrus Broenniman visits the burial place of her ancestors in Kozma Street Cemetery in Budapest, Hungary, on Sept. 3, 2023. Photo courtesy Linda Ambrus Broenniman

There was this duality because clearly they loved Hungary. They were true patriots. I think they thought of Hungary as their country and Judaism as their religion. They believed in the Jewish faith, and they were proud of the Jewish faith, and they weren’t going to give it up. I think they believed this was just a blip and once it was over, Hungarians would go back to the way it was before the war where they were assimilated and accepted. They weren’t always 100% accepted, but for the most part they were accepted, and they were key to building that Golden Age of Budapest.

Reading your book I was reminded of another prominent Hungarian Jew, George Soros. This kind of antisemitism is still around, isn’t it?

In 2019, when I was there, (Prime Minister Viktor) Orbán had really been on a tirade. It was horrible, the kinds of things they were doing in Hungary to vilify Soros. Soros finally had to pack up this Central European University and move it to Vienna, which is a huge tragedy. The CEU was an incredible educational institution. Orbán used incredible tactics to vilify Soros. He put pictures of Soros on the floors of the trams so people had to step on his face — these kinds of things are just horrific.

Was there any relationship between the Politzers and the Soroses?

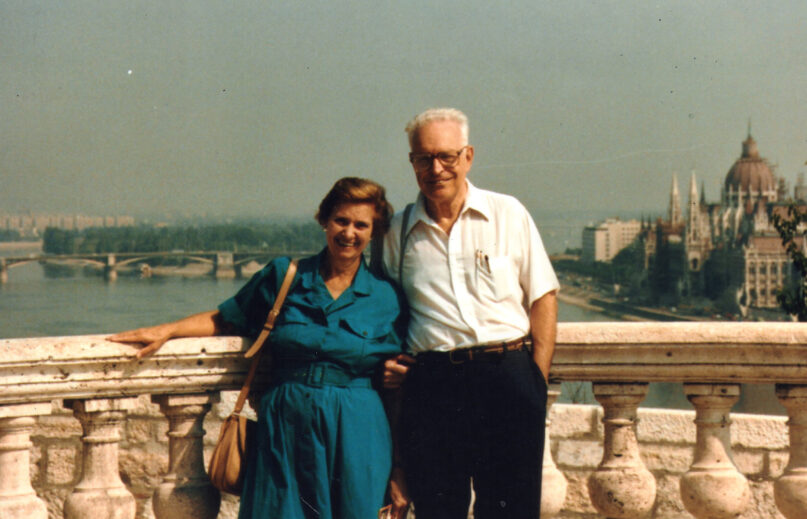

Julian and Clara Ambrus in 1945. Photo courtesy Linda Ambrus Broenniman

I’m sure they knew each other because they were lawyers.

Were your parents believers?

Absolutely. My father believed that the fact they lived was a miracle. They should have been killed. I think his faith was in God. Whether it was a Catholic God or Jewish God, I don’t know if that made a difference to him. He believed God had given him life, had saved his life, and he needed to use that life to help humanity. His way to help humanity was to become a doctor and help save lives and try to cure disease. Everyone went to church.

Are you still a practicing Catholic?

No, I really haven’t been since my early years. I’m very spiritual, but organized religion has never really spoken to me. I’m very proud of my parents and proud of my Jewish heritage. But religion itself hasn’t been important to me in my life.

But do you feel like a Politzer now?

Margit and Gyula Politzer, Linda’s great-grandmother and grandfather. Photo courtesy Linda Ambrus Broenniman

Yes, I do. For a long time, it was just these people I was researching. I did a lot of historical research so I could understand their lives and the context and zeitgeist of the times in which they lived. By writing it, I felt so connected to them. And then it just struck me one day when I was on a Zoom call and I was introduced as a Politzer that, ‘Oh my God, yes, I am a Politzer.’ It was just this deep connection that really went right to my heart. They’re my family. And I think when you look at these people and what they went through — all of these hardships, and their resilience — it’s remarkable, their values, their focus on education and truth and justice. They just are these remarkable people.

How do you relate your story to what’s going on today with the rise in antisemitism?

You know, we really have to understand the consequences of our actions and our words. There’s no place for hatred and dehumanization. That’s not gonna get us anywhere. We need to respect one another and understand our own stories. I know for me, it’s been such a gift to really learn where I came from. I would hope that others would do the same, learn about themselves and learn about history so we can have positive conversations and respect one another and sort of glorify our differences. It’s wonderful to be different. We don’t want everyone to be the same. It’s what makes this world beautiful.