(RNS) — Kate Cohen is full of contradictions.

The author and Washington Post columnist taught her children that God is a fictional character and encourages her fellow nonbelievers to be honest about their disbelief. On the other hand, Cohen, who was raised Jewish, prays at times and worries about the future of churches.

“Okay, everyone: It’s time to go back to church,” Cohen wrote in a recent column for the Post, recommending a Sunday service, or something like it, even for atheists like herself.

Cohen’s point was this: During the COVID-19 pandemic, Americans lost the habit of gathering, whether in houses of worship or theaters, to find “participatory transcendence.”

Such places, where people can belong to each other and create meaning together, may seem superfluous to human existence.

But they matter, Cohen believes.

“You don’t need a church,” Cohen told Religion News Service in a recent interview. “You can survive without one, and yet we’ve built these spaces that are about abstract ideas. I find that to be a beautiful thing.”

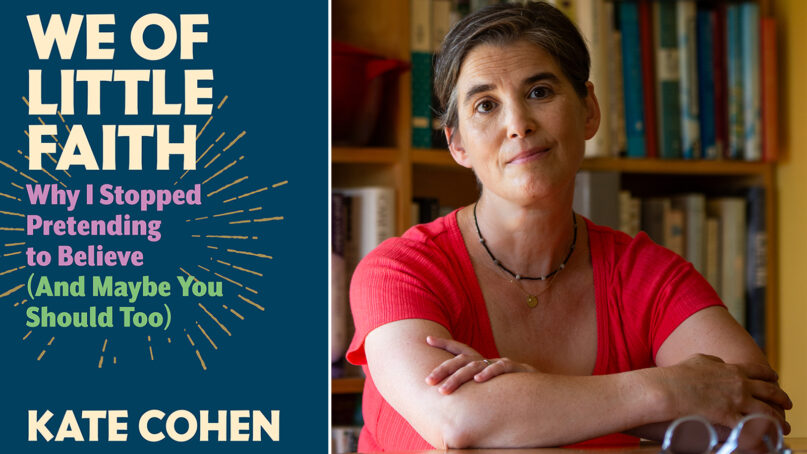

Cohen writes about the meaning-making power of communal gatherings, rituals and holidays in her new book, “We of Little Faith,” out this week from Godine, an independent publisher based in Boston.

Kate Cohen. Photo by KT Kanazawich

Subtitled “Why I Stopped Pretending to Believe (and Maybe You Should Too),” the book is part memoir and part call to her fellow nonbelievers to be more open about being atheist. It’s also a cheerful and good-natured guide to a meaningful life without God.

While about 1 in 3 Americans (29%) claim no religious affiliation, only 1 in 25 (4%) claim to be an atheist, according to Pew Research Center. Others claim to be agnostic (5%) or have no religion in particular (20%).

But Cohen suspects the number of people who would qualify as atheists because they don’t believe in God is higher than Pew reports. Too many of her fellow nonbelievers, argues Cohen, are tempted to hide their lack of faith in God — often out of fear of what others may think, or because of the stereotypes that come along with the term “atheist.”

Or because they want to have “pleasant, easy interactions with people” and don’t want to be seen as problematic: In the public eye, she said, atheists are seen as humorless and angry at anyone who believes.

“People think that atheists are bad people,” said Cohen.

But fear of being honest comes with a cost. In the book, Cohen describes pretending to be observant while visiting with Jewish family members in Italy, and how that pretending widened the chasm between them.

Cohen said that we lose something when we don’t admit who we really are. “When you lie, you’re really creating a barrier between yourself and other people,” she said. “I think I lost the possibility of being closer to those people than I was.”

A native of Virginia who now lives in upstate New York, Cohen recounts how a conversation with a Christian doctor helped her become more honest about her atheism. Cohen and her family were back home on vacation, and her son needed a place to practice the piano. The doctor opened his home, and while her son practiced, the two adults chatted.

When the conversation turned to religion, Cohen said she did not believe in the supernatural, and the doctor opened up about his own doubts.

“We all go around — I once did, too — assuming that everyone else is a believer,” she writes. “I’ll bet every private atheist in America knows someone who thinks they’ve never met an atheist before.”

Then she added: “We won’t know the truth until we tell the truth.”

Much of the book retells how Cohen has found meaning in life as an atheist — raising children, making friends and learning how to cultivate gratitude. While having children leads some people back to a house of worship, for Cohen it had the opposite effect.

As a mother, Cohen said she became aware of the overwhelming responsibility of teaching her kids what it means to be human — everything from how to tie their shoes or make a sandwich to how to lead a meaningful life and deal with death.

“I had an aversion to telling them anything I knew, or suspected, was untrue,” she said. “I’m not going to tell them the cat went to heaven — even though in the moment that might be the easiest thing to do.”

That also meant telling her kids there was no proof that God existed. That conversation, she recounts, began while reading a popular library book about Greek myths. Just as the Greeks made up stories of their gods to explain how the world works, so people of other faiths made up their own gods, she told her kids.

“God is a human invention,” she said in an interview.

In the absence of religion, Cohen spent time trying to help her kids find community and create meaningful rituals. For years, she said, her kids’ music school became their church — a community where they joined others in a common purpose.

“We paid to belong; we grumbled about the policies; and we felt ourselves fortunate to have found the place, so fortunate that we even tried to get our friends to join,” she said. “And all the members of that community were there because we shared a belief in the same higher power: not God, in this case, but music.”

Cohen said her book isn’t meant to convince people who believe in God they’re wrong. She often feels she has a great deal in common with her religious friends because they are intentional in how they live.

She’s also a big fan of holidays. International Pizza Day, which her family celebrates every February 4th, includes making homemade crusts and gathering friends — traditions that gave the day meaning.

She loves Thanksgiving because of the holiday’s focus on being grateful and because in the United States, almost everyone celebrates. That gives a sense of communal belonging that International Pizza Day — no matter how her family loves it — does not have.

At her house, Thanksgiving includes communal prayer — just not to God.

“One of the reasons so many people ascribe the name God to things that aren’t, in my view, God at all, is that God is the biggest word that they have, you know, to describe the biggest feelings they have,” she said. “Prayers and public words can channel that sort of communal resolve or inspiration.”