BISHOP AUCKLAND, England (RNS) — The town’s name is a reminder of its history as the county seat of the bishop of Durham, one of England’s most powerful clerics. But by the end of the last century, Bishop Auckland had become a shadow of its former self, with shops on its main street boarded up, the nearby coal pits closed down and work hard to come by. But now a remarkable experiment is underway — to revive the fortunes of this northern England town through a combination of art and religion. And the final piece in its regeneration — a Faith Museum — opened its doors for the first time Saturday (Oct. 7).

Britain has plenty of medieval cathedrals and ancient monuments, but the Faith Museum is the first of its kind solely dedicated to telling the story of the country’s religious faith. And it is a dramatic story — tumultuous, often violent and always tied closely to the country’s own identity and place in the world. The museum has items highlighting the birth of Christianity under Roman rule, the power of the medieval monasteries, the polarizing effects of the Reformation, the growth of dissenting Christian traditions, the challenge of science to faith and the religious diversity of today.

The Faith Museum is the brainchild of one of Britain’s richest men, city of London investment banker Jonathan Ruffer, who was raised not far from Bishop Auckland. He has spent the last 10 years creating what he calls the Auckland Project, a series of museums, galleries, parks and other attractions.

Ruffer, who first became an active Christian at Cambridge University in the late 1960s, says the Auckland Project would never have come about if he had not undertaken an eight-day Ignatian silent retreat 10 years ago.

“It was simply supposed to be a wash and brush up, but when I was there I was mugged (by God), challenged to turn my life into one that was working with the voiceless wherever I chose. Being unimaginative, I thought it best to return to my roots here.”

Auckland Castle in Bishop Auckland, northern England. Photo by Peter Haygarth, courtesy The Auckland Project

Ruffer recalls that during the retreat, people staying at the Jesuit house in Wales were told at the start that a priest and a kitchen worker were ill. Each day, they were given updates on the priest but not on the kitchen worker. He was shocked.

“I found myself shaking my fist and saying to God, ‘Who’ll look after the little person?’ The answer came straight back. So that’s a dangerous question to ask,” Ruffer says.

“It was clear it was what I was called to do. The key was accepting what it was. I always define it as an Abrahamic call, in that I was clearly being sent on a journey, and, like Abraham, I wasn’t vouchsafed the destination. I really have spent years not knowing what I was doing.”

There is no sense in Bishop Auckland that Ruffer was clueless. Rather, he has responded to opportunity.

While he was looking for something to do that would make a difference, the Church Commissioners, who look after the Church of England’s money, were at the same time looking to offload a set of paintings — “Jacob and His Twelve Sons,” by the Spanish master Zurbarán. They had been purchased in 1757 by Richard Trevor, bishop of Durham, and had since been displayed in the dining room of the bishop of Durham’s castle in Bishop Auckland.

Ruffer has a particular passion for Spanish art and a substantial collection of his own, which now forms the collection in another of the town’s new museums — Bishop Auckland’s Spanish Gallery, filled with works by Spanish Old Masters, including Velazquez, El Greco and Murillo.

Jonathan Ruffer outside The Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland. Photo courtesy House of Hues

Although he was attracted to the idea of taking on the Zurbarán masterpieces, negotiations with the Church Commissioners were fraught. The Zurbaráns came with the castle, and they wanted £15 million. Ruffer says he never wanted to take on a building — “I don’t like them, I’m frightened of them” — and viewed the castle as a liability that needed considerable repair.

At one point he walked away from the deal but was drawn back, he says, by the then-bishop of Durham’s efforts. Justin Welby, now archbishop of Canterbury, brought about reconciliation between him and the commissioners — a venture that partly involved meeting in a peace yurt at a church in the city of London. After first offering £15 million for the Zurbarán, he finally secured the castle and the pictures for £11 million.

The Zurbaráns remained in the castle dining room — where visitors can now see the biblical figures of Jacob and his sons, once purchased by Bishop Trevor to publicly show his support for Jewish naturalization rights at a time when the British Parliament was debating them. And the castle itself became the locus for the Faith Museum, which now occupies a separate old part of the castle, as well as a new extension built for the museum.

Ruffer says the Spanish Gallery reflects ideas of transience and eternity. While it also reflects his personal passion for the art of the Spanish Baroque, he says it is the newly opened Faith Museum that is closest to his heart. He describes it as his “comfort food for taking on the castle.”

“What I could see was that there is no faith museum anywhere, and the fact that it’s taken us 10 years to get to — it was the only specific, tangible thought I had, and it’s the last thing to fall into place.”

The Auckland Castle Long Dining Room in 2015, prior to conservation, showing “Jacob and His Twelve Sons” portraits by Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán. Photo © Colin Davison, courtesy The Auckland Project.

Ruffer — who claims that when he became a Christian, it was “not because I needed it but because it was true” — says he is not on a mission to proselytize with the Faith Museum, but rather to explain.

“I do think that what we are trying to do here hasn’t been done before. That doesn’t make us pioneers. It hasn’t been tried because it is impossible in an age like this when there is such an animus against people with faith, and those with faith are often vituperative toward others with faith.”

The Museum begins with a gallery tracing the origins of faith in Britain from 6,000 years ago and ends with contemporary artists and their personal responses to faith. In between are timelines and accounts of the dramatic twists and turns of faith in Britain and a collection of more than 250 objects from private and personal collections across Britain, many on loan as the Faith Museum works to build its own collection.

Among the highlights is a never-before-displayed object found less than a mile from the castle: the Binchester Ring. The silver ring was discovered during an excavation in 2014 at Binchester Roman Fort, and its carved carnelian stone inscribed with an anchor and fish is rare early evidence of Christianity in Britain.

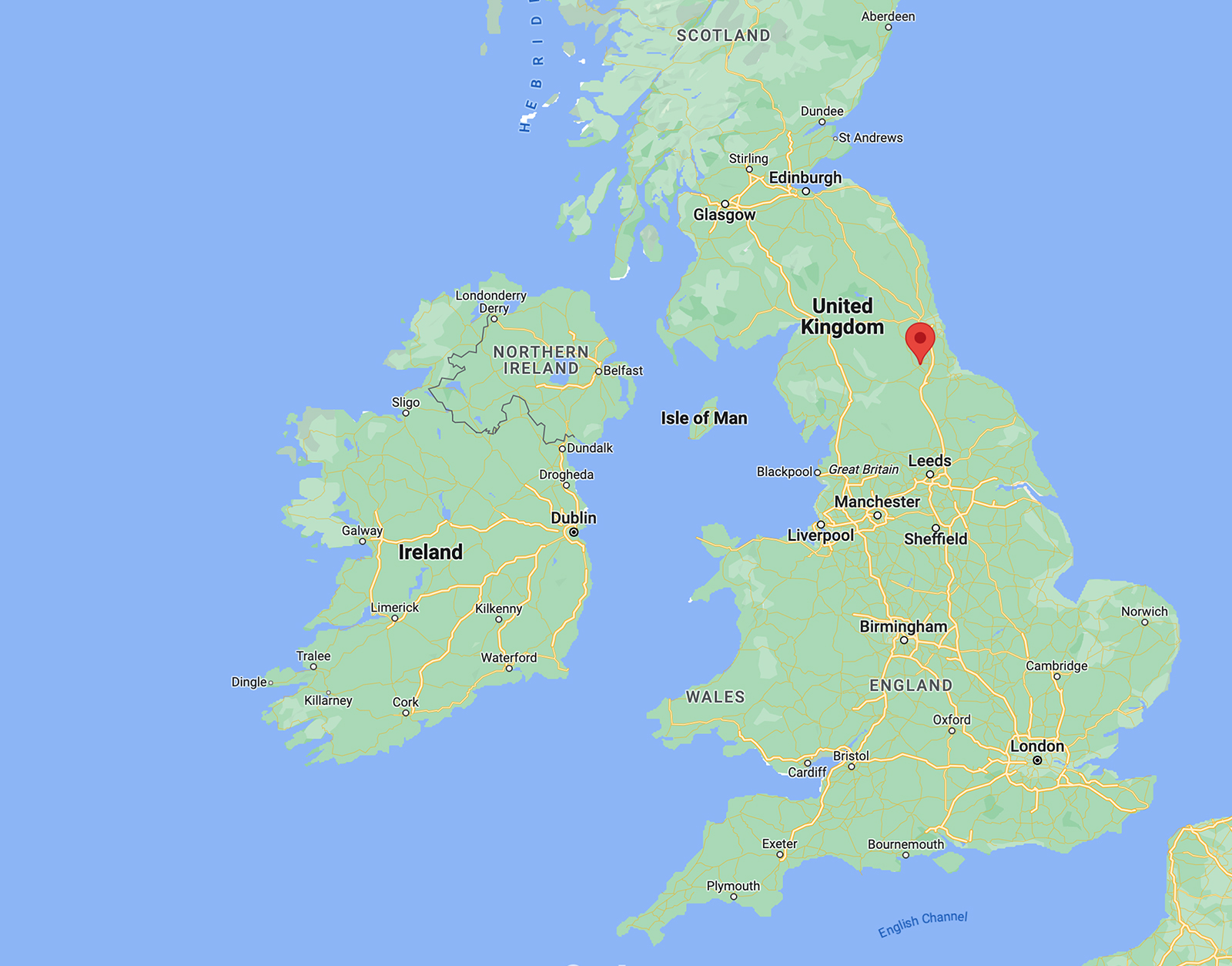

Bishop Auckland, red, in northern England. Image courtesy Google Maps

A number of items on display highlight the various religious conflicts in Britain’s history, particularly the Reformation. An altar cover made from fragments of embroidered blue velvet, likely created after 1600 from vestments worn by pre-Reformation priests, symbolizes efforts to preserve the Catholic faith. There is also a 1535 document listing the annual incomes of 160 monasteries around Britain, after Henry VIII decided to tax them. Eventually he had them dissolved.

There is a rare example of William Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament — a translation that led to his execution for heresy in 1536. Also on display is a wooden pulpit from 1760, from which the Methodist preacher John Wesley spoke when he visited the north of England.

A number of items in the museum point to the history of Christian charity in the country, including a set of brass musical instruments made at the Salvation Army’s own musical instrument factory.

The presence of other religions in Britain is also highlighted in the displays, including the 13th-century Bodleian Bowl, an early example of evidence of Jewish communities in Britain. This decorated bronze vessel is inscribed with the name of Joseph, son of Rabbi Yechiel, a famous Parisian Torah scholar. Joseph lived in Colchester and may have given this bowl to the Jewish congregation there before leaving for the Holy Land. There are also the prayer beads of Lord Headley, the first convert to Islam in Britain, who became a Muslim in 1913.

Amina Wright, the senior curator of the Faith Museum, says all the items on display form a narrative of faith: “Every object is seen as a witness to faith, showing the impact of faith on Britain.” But when it comes to the present century, Wright said the task is more complicated. “We can’t explain the last 23 years in the same way. We need more distance to gain a perspective,” she said, also noting the difficulty for curators in finding physical objects for today’s faith experiences, when so much is digital.

Paintings showing early influences on Spanish Golden Age art at The Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland, England. Photo courtesy House of Hues

The larger Bishop Auckland rejuvenation efforts have received an additional £12.4 million from the British National Lottery as well as grants from other philanthropists. Government regeneration money has also poured into post-industrial Bishop Auckland, while Ruffer himself has spent well over £100 million. Three charities have been created to run the projects, with one, the Zurbarán Trust, holding the paintings and other valuables.

Ruffer’s Bishop Auckland revival also includes a Spanish tapas bar, adjacent to the Spanish Gallery, and a hotel. Together with an annual summer pageant known as Kynren and plans for a leisure park, the revitalization efforts aim to attract between 1 to 1.5 million visitors a year by 2028, said Ruffer, even though the town is off the beaten track and without a direct railway or motorway to London.

Next up, Ruffer hopes to purchase the 6-meter-long gold braid tapestry called “Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books,” which was commissioned by Henry VIII when he declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. Ruffer describes it as “the birth certificate of the Church of England.” It was missing for years but turned up in Spain. The Spanish government says it can return the artifact to Britain if the Faith Museum can raise £4.55 million. Ruffer is looking for donations, and a space for it in the Great Gallery at the Faith Museum awaits.